Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 7

Utility of Prosthetic Extremities among Lower Limb-Post Amputation Patients and its Effect on Quality of Life, Jeddah, KSA

Bayan Foaud Mogharbe* and Areej Taher Bensadek

*Correspondence: Bayan Foaud Mogharbe, Consultant Community and Preventive Medicine, Consultant Infection Control, IPC Certified CBAHI Surveyor, Examiner Member in Saudi Commission, Saudi Arabia, Email:

Abstract

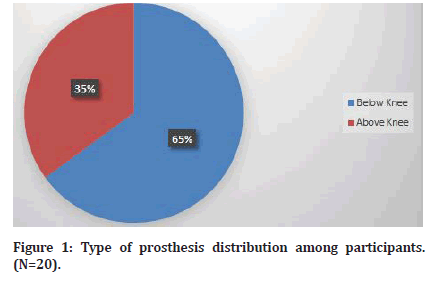

Background: A lower limb amputation is a surgical invasive procedure in which the patient's legs are severed, either one or both. Trauma, infection, diabetic foot, and occlusive disorders of the arteries are among the reasons. The amputation has a huge impact on the patients' lives, resulting in a severe reduction of their physical, psychological, and social well-being. Prosthetics have been shown to increase patient function and independence in most aspects of everyday life. Exploring the patients' beliefs, challenges, barriers, and enablers is critical. Objective: To investigate the social and psychological aspects of post-amputation among afflicted patients in Jeddah, KSA. Methods: Quality of life and prosthesis utility assessment were performed among amputee patients with prosthesis and without in this descriptive, analytical cross-sectional study. The study assessed quality of life and prosthesis utility at single point of time which makes the cross-sectional design suitable. Data was collected using The Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scale - Revised (TAPES-R). The research is open to all participants who have had a lower limb amputation and can communicate in Arabic. Those who use prosthetics will also be included. Results: The study included 40 participants divided into two groups; 20 participants who had lower limb amputation and are using prosthesis and 20 participants who had an amputation only. Among participants who used prosthesis, the mean duration for prosthesis use was 5.1 ± 2.04 years and the mean duration of use for the current prosthesis was 3.57 ± 1.67, which indicates that these participants changed their prosthesis after two years from the first use. Prosthesis type varied among participants who used it as demonstrated in figure 1. Below knee prosthesis was used among 13 participants while above knee prosthesis was used among 7 participants. The mean score of satisfaction among participants was 5.28 ± 1.552 out of 10. Participants who use prosthesis reported a mean duration of wearing the prosthesis for 12.42 ± 3.80 hours per day. Conclusion: Physical capacity is poorer in amputee patients than in prosthesis amputee patients; contentment with prosthesis and body image are unrelated to amputation level; and life quality and satisfaction with prostheses rise in tandem with prostheses use. Clinical significance although there are disparities between the groups in terms of quality of life and functioning, patients with appropriate rehabilitation and a proper prosthesis can achieve an acceptable living standard.

Keywords

Prosthetics, Amputation, Rehabilitation, Prosthesis

Introduction

Lower extremity amputation is a surgical operation that causes long-term negative effects in several parts of the patients' lives, ultimately affecting their quality of life [1]. Lower limb ischemia, trauma, diabetic foot infection, necrotizing vasculitis, malignancies, and intraarterial injections among drug addicts are the most common reasons for amputation [2]. One of the most well-known significant causes of lifelong impairment is amputation. Other disorders that can be linked to amputation include mental ailments including anxiety, solitude, and depression, which can have a substantial impact on a patient's physical and social well-being [3]. The loss of a lower limb, according to Laplante, is the most common cause of functional impairment [4]. Surgeons, rehabilitation experts, and prosthetists have all worked to improve amputation outcomes and raise the possibility of patients returning to their prior normal lives [5].

Between 2005 and 2016, there were 20,062 amputations in the city of Ontario in Canada [6]. According to earlier studies, around 325 amputations are anticipated to occur each year in Jeddah [7]. The diabetic foot is the most prevalent cause of amputation in Jeddah, accounting for more than half of all amputations [8]. In fact, research conducted in Saudi Arabia to investigate the risk factors for amputation in diabetic foot ulcers found that only older age and a high white blood cell count were substantially linked with ulcer amputation [9]. However, research suggests that in Saudi Arabia, diabetic foot ulcers can be regarded as a single primary risk factor for amputation.

Literature Review

Previous studies assessed the overall results of lower limb amputations using a variety of markers [10]. Walking distance, for example, is a significant factor of health and quality of life in the assessment of mobility and function [11]. Prosthetic use and satisfaction are further drivers; 84 percent of respondents were happy with the fit and function of their prosthetic device [12]. Pain, skin residuals, and discomfort were commonly documented in the literature to further clarify the results after amputation. Employment among amputees is also a major challenge. Amputees' employment rates and their return to prior jobs ranged from 48% to 89 percent. Other characteristics, such as the location of the amputation, age, educational level, and psychosocial adjustment, were found to impact returning to the same career [10]. It is worth that maintaining a position once hired or obtained is exceedingly tough for all amputees [13]. Physical comparisons with normal controls and/or intact limbs revealed lower transitional limb knee and limb hip muscles in a review by Hewson et al. [14].

In a qualitative study of amputees in a rural part of South Africa, researchers looked at the challenges and facilitators they faced. Environmental (lack of transportation and lack of knowledge), financial (difficulty attending therapy and loss of freedom), and impairments were recognized as three major barriers (pain and depression). Environmental (referral system and favorable experience with physiotherapy treatments) and personal factors were both facilitators (selfmotivation and family support) [15]. Negative themes for pre-prosthetic rehabilitation were also discovered in South Africa, including a lack of governmental assistance, poor socioeconomic position, and cultural variables that impact recovery [16]. Walking ability, usage of prosthesis, level of amputation, comorbidities, and socioeconomic status were found as variables impacting the quality of life of patients with lower limb amputation owing to peripheral artery occlusive disorders in a systematic review of the literature [17]. There were six themes identified in a qualitative study in Nepal that interviewed a total of 16 prosthesis users:

importance of prosthesis for mobility, pain, difficulty in employment, appreciation of physiotherapy with other amputees, satisfaction with health care, and negative self-image due to limited ability [18].

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines quality of life as "an individual's assessment of their situation in life in respect to their objectives, aspirations, standards, and concerns in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live." It's a wide term influenced by a person's physical condition in a complicated way." [19]. Richa Sinha et al. conducted a cross-sectional study in Mumbai in 2013 about adjustments to amputation and an artificial limb in lower limb amputees. Faceto- face interviews were conducted using structured questionnaires, which included the Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scales analyzed, which consists of psychosocial adjustment subscales (general adjustment, social adjustment, and adjustment to limitation), and activity restriction subscales (functional, athletic, and physical activity restriction) (functional, aesthetic and weight satisfaction). The overall scores of the TAPES subscales revealed that amputees were generally content with the improvement they experienced with prosthesis, and that wearing a prosthesis was linked to being more socially adjusted as well as being better adjusted to the limitations imposed by the amputation. Being a man and being older were linked to having a better social life. Being younger was linked to having less functional and social limitations [20].

Quality of life (QOL) and emotional status were both reported to deteriorate among male patients with lower limb amputation in the literature (LLA). Body image disturbance, sadness, and anxiety were already identified as predictors of patients' QOL in previous studies. Lower function and more post-amputation discomfort were linked to poor QOL. The emotional state of LLA patients is connected to their body image perception. They stated in a prior study that amputee rehabilitation should focus on improving psychological factors such as anxiety, sadness, post-amputation pain, and improving body image [21].

Rationale

Prosthetic limb extremities are the most common form of intervention for lower limb post amputation patients, as a means of addressing cosmetic, functional rehabilitation, and quality of life. Continuous quality improvement among post amputees necessitates assessing the effect of prosthetic extremities. Furthermore, no extensive study has been conducted on lower limb prosthetic extremities following amputation and their impact on quality of life.

Aim of the study

Determine the hurdles to being without prosthetic extremities, to reduce suffering and to increase quality of life among post-amputation patients.

Objectives

â?? To investigate the social and psychological implications of amputation among amputees in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

â?? To compare the quality of life among post amputation patient with prosthetic extremities and without prosthetic extremities in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Secondary

To identify the obstacles of inability to insert prosthetic extremities among amputees in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Methodology

Study design

This quantitative descriptive, analytical cross-sectional research looked at the psychological and social elements of patients who have had limbs amputated. The data for the study was collected through a questionnaire.

Study population

Any adult patient above 18 years old post amputation with and without prosthetic extremities.

Inclusion criteria

â?? Age of 18 years old or alder.

â??Patients who experienced an amputation in the lower limb.

â?? Patients who have a prosthetic lower limb.

Exclusion criteria

â?? Patients who cannot speak Arabic.

â?? Patients who experienced amputations in the upper limb only.

Study area

The study was conducted in Jeddah city, at two tertiary care rehabilitation centers that provide post amputation care. Abdullatif Jameel hospital private sector was used to include patients with prosthetic extremities. While king Fahad hospital was to include patients without prosthetic extremities.

Sample size

We estimate the total sample size to be around 40 divided into two groups: 20 amputee patients with prosthesis and 20 amputee patients without prosthesis.

Sampling technique

We used a purposive sampling to include equal number of patients between those who have a prosthetic limb and those who do not have.

Data collection

Data will be collected using self-designed questionnaire. Study questionnaires consisted of sociodemographic data, amputation history data and assessment tools according to The Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scale-Revised (TAPES-R).

Data analysis

Data obtained from questionnaire were entered and analyzed using SPSS program version 23 computer software. Sociodemographic data are presented using descriptive statistics as means, median, percentages and standard deviation. Independent T test and one-way Anova are used to show statistical significance among patients’ characteristics and tool scores. Chi square test is used to show relationship between categorical variables.

Pilot study/pretesting

A pilot study will be conducted using one focus group discussion to examine the feasibility of the data collection. Primary open-ended questions can be modified if necessary, according to the experiment of the pilot group discussion.

Ethical considerations

Approval from the Saudi board of community medicine research committee and from the ministry of health in Jeddah will obtained before the start of the study, all participants gave their written informed consent before enrolment.

Results

The study included 40 participants divided into two groups; 20 participants who had lower limb amputation and are using prosthesis and 20 participants who had an amputation only. The mean age between two groups varied significantly as participants who used prosthesis were younger than participants who don’t. Participants’ characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Amputation with prosthesis (N= 20) | Amputation only (N= 20) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 14 | 13 | 0.078 |

| Female | 6 | 7 | ||

| Age group | Less than 18 | 1 | 1 | 0.004 |

| 19-25 | 9 | 1 | ||

| 26-35 | 4 | 3 | ||

| 36-40 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 41-55 | 3 | 5 | ||

| 56 or more | 2 | 9 | ||

| Nationality | Saudi | 15 | 15 | 0.078 |

| Non-Saudi | 5 | 5 | ||

| Smoking | Yes | 10 | 11 | 0.068 |

| No | 10 | 9 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 15 | 12 | 0.058 |

| Divorced | 1 | 2 | ||

| Single | 3 | 5 | ||

| Widow | 1 | 1 | ||

| Occupation | Employed | 12 | 3 | 0.021 |

| Not employed | 8 | 17 | ||

| Presence of Diabetes Mellitus | Yes | 2 | 13 | <0.001 |

| No | 18 | 7 | ||

| Duration (Years) of amputation (Mean + SD) | 6.5 + 1.1 | 8.07 + 4.1 | <0.001 | |

Table 1: Characteristics of study participants.

Among participants who used prosthesis, the mean duration for prosthesis use was 5.1 ± 2.04 years and the mean duration of use for the current prosthesis was 3.57 ± 1.67, which indicates that these participants changed their prosthesis after two years from the first use. Prosthesis type varied among participants who used it as demonstrated in Figure 1. Below knee prosthesis was used among 13 participants while above knee prosthesis was used among 7 participants.

Figure 1: Type of prosthesis distribution among participants. (N=20).

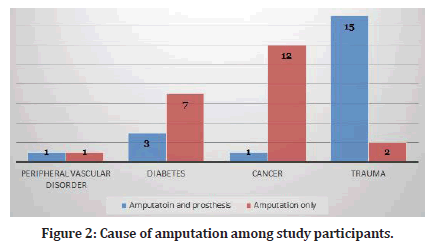

The cause of amputation varied among study participants as shown in Figure 2. The variation of amputation cause was statistically significant as patients who use prosthesis had amputation mostly due to trauma. On the other hand, patients who don’t use prosthesis had amputation due to chronic condition such as diabetes or cancer as presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Cause of amputation among study participants.

Use of prosthesis

It is noticed from the table that study participants who are using prosthesis are generally disagreeing to agreeing with scale items. Activities during a typical day among participants who are using prosthesis (Tables 2 and Table 3).

| Item | Response | Mean | SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |||

| 1. I have adjusted to having a prosthesis | 4 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 2.05 | 0.714 |

| 2. As time goes by, I accept my prosthesis more | 7 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 2.1 | 0.955 |

| 3. I feel that I have dealt successfully with this trauma in my life | 1 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 2.58 | 0.844 |

| 4. Although I have a prosthesis, my life is full | 7 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 2.3 | 1.043 |

| 5. I have gotten used to wearing a prosthesis | 3 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 2.6 | 1.081 |

| 6. I don’t care if somebody looks at my prosthesis | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 2.45 | 1.131 |

| 7. I find it easy to talk about my prosthesis | 2 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 2.48 | 0.847 |

| 8. I don’t mind people asking about my prosthesis | 4 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 2.48 | 0.933 |

| 9. I find it easy to talk about my limb loss in conversation | 3 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 2.3 | 0.758 |

| 10. I don’t care if somebody notices that I am limping | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 2.4 | 1.008 |

| 11. A prosthesis interferes with the ability to do my work | 4 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 2.35 | 0.893 |

| 12. Having a prosthesis makes me more dependent on others than I would like to be | 4 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 2.43 | 1.01 |

| 13. Having a prosthesis limits the kind of work that I can do | 1 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 2.55 | 0.783 |

| 14. Being an amputee means that I can’t do what I want to do | 4 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 2.3 | 0.853 |

| 15. Having a prosthesis limits the amount of work that I can do | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 2.63 | 1.079 |

| Overall | 2.39 | 0.239 | ||||

Table 2: Participants responses to use of prosthesis scale items (N=20).

| Item | Response | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, limited a lot | Limited a little | No, not limited at all | |

| (a) Vigorous activities, such as running, lifting heavy objects, participating in strenuous sports | 3 | 8 | 9 |

| (b) climbing several flights of stairs | 5 | 8 | 7 |

| (c) running for a bus | 2 | 10 | 8 |

| (d) sport and recreation | 3 | 9 | 8 |

| (e) climbing one flight of stairs | 4 | 10 | 6 |

| (f) walking more than a mile | 5 | 9 | 6 |

| (g) walking half a mile | 4 | 9 | 7 |

| (h) walking 100 meters | 3 | 10 | 7 |

| (i) working on hobbies | 4 | 9 | 7 |

| (j) going to work | 5 | 8 | 7 |

Table 3: Participants responses to frequency of performing activities during a typical day (N=20).

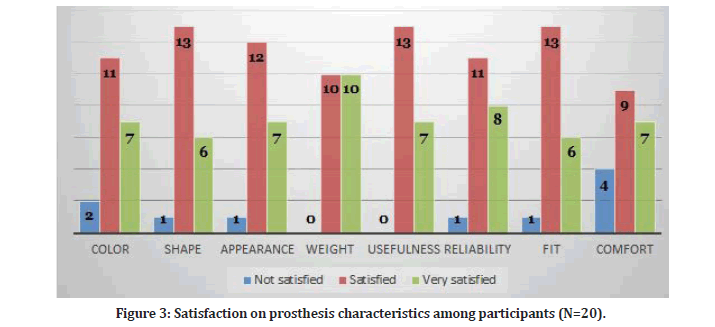

Participants who are using prosthesis were asked about their satisfaction level with regard to prosthesis characteristics as illustrated in Figure 3. The mean score of satisfaction among participants was 5.28 ± 1.552 out of 10. Participants who use prosthesis reported a mean duration of wearing the prosthesis for 12.42 ± 3.80 hours per day. The baseline characteristics of study participants had affected their responses to previous three scale items. Regression model analysis is presented in Tables 4-6. Quality of life varied significantly among prosthesis patients and amputated patients. Table 7 shows their responses to questions and the statistical significant level.

| Variable | Coefficient of regression | 95% Confidence interval | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||

| Gender | 0.126 | -0.112 | 0.365 | 1.085 | 0.287 |

| Age | -0.077 | -0.18 | 0.026 | -1.529 | 0.138 |

| Smoking | 0.075 | -0.138 | 0.288 | 0.723 | 0.476 |

| Marital Status | -0.05 | -0.143 | 0.043 | -1.111 | 0.276 |

| Occupation | -0.046 | -0.239 | 0.148 | -0.482 | 0.633 |

| Presence of DM | 0.025 | -0.3 | 0.35 | 0.159 | 0.875 |

| Amputation duration | -0.025 | -0.115 | 0.065 | -0.569 | 0.574 |

| Prosthesis duration | 0.039 | -0.059 | 0.135 | 0.814 | 0.422 |

| Prosthesis type | 0.011 | -0.054 | 0.076 | 0.337 | 0.738 |

| Amputation Cause | -0.109 | -0.298 | 0.08 | -1.185 | 0.246 |

Table 4: Linear regression analysis between participants characteristics and use of prosthesis scale items (N=20).

| Variable | Coefficient of regression | 95% Confidence interval | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||

| Gender | -0.035 | -0.29 | 0.22 | -0.28 | 0.782 |

| Age | -0.03 | -0.14 | 0.081 | -0.549 | 0.587 |

| Smoking | 0.153 | -0.074 | 0.381 | 1.38 | 0.179 |

| Marital Status | 0.001 | -0.099 | 0.1 | 0.011 | 0.991 |

| Occupation | -0.121 | -0.328 | 0.086 | -1.195 | 0.242 |

| Presence of DM | 0.088 | -0.26 | 0.436 | 0.517 | 0.609 |

| Amputation duration | 0.027 | -0.069 | 0.123 | 0.573 | 0.571 |

| Prosthesis duration | -0.042 | -0.145 | 0.062 | -0.826 | 0.46 |

| Prosthesis type | 0.006 | -0.064 | 0.076 | 0.179 | 0.859 |

| Amputation Cause | -0.207 | -0.409 | -0.005 | -2.098 | 0.045 |

Table 5: Linear regression analysis between participants characteristics and performing activities during a typical day (N=20).

| Variable | Coefficient of regression | 95% Confidence interval | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||

| Gender | 0.003 | -0.261 | 0.267 | 0.025 | 0.98 |

| Age | 0.023 | -0.091 | 0.137 | 0.417 | 0.68 |

| Smoking | 0.012 | -0.224 | 0.247 | 0.101 | 0.921 |

| Marital Status | -0.057 | -0.159 | 0.046 | -1.128 | 0.269 |

| Occupation | 0.13 | -0.085 | 0.344 | 1.24 | 0.225 |

| Presence of DM | -0.116 | -0.475 | 0.244 | -0.658 | 0.516 |

| Amputation duration | 0.05 | -0.049 | 0.149 | 1.03 | 0.312 |

| Prosthesis duration | -0.027 | -0.134 | 0.08 | -0.518 | 0.609 |

| Prosthesis type | -0.022 | -0.094 | 0.05 | -0.632 | 0.533 |

| Amputation Cause | 0.159 | -0.05 | 0.368 | 1.561 | 0.13 |

Table 6: Linear regression analysis between participants characteristics and prosthesis characteristics (N=20).

| Variable | Prosthesis group (N= 20) | Amputation group (N= 20) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Health | Very poor | 3 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Poor | 4 | 4 | ||

| Fair | 2 | 5 | ||

| Good | 7 | 2 | ||

| Very good | 4 | 2 | ||

| Physical capabilities | Very poor | 3 | 5 | <0.001 |

| Poor | 2 | 8 | ||

| Fair | 4 | 7 | ||

| Good | 8 | 0 | ||

| Very good | 3 | 0 | ||

| Stump pain | Yes | 7 | 14 | 0.004 |

| No | 13 | 6 | ||

| Stump pain level | Excruciating | 1 | 4 | 0.035 |

| Horrible | 2 | 6 | ||

| Distressing | 4 | 4 | ||

| Mild | 13 | 6 | ||

| Stump pain effect on lifestyle | A lot | 5 | 8 | <0.001 |

| Quite a bit | 2 | 4 | ||

| Moderately | 1 | 1 | ||

| A little bit | 8 | 3 | ||

| Not at all | 4 | 4 | ||

| Phantom limb pain | Yes | 6 | 15 | <0.001 |

| No | 14 | 5 | ||

| Phantom limb pain level | Excruciating | 3 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Horrible | 2 | 4 | ||

| Distressing | 1 | 6 | ||

| Mild | 14 | 3 | ||

| Phantom limb pain effect on lifestyle | A lot | 0 | 6 | <0.001 |

| Quite a bit | 3 | 3 | ||

| Moderately | 5 | 7 | ||

| A little bit | 5 | 3 | ||

| Not at all | 7 | 1 | ||

| Need assistance to fill the questionnaire | Yes | 3 | 5 | 0.078 |

| No | 17 | 15 | ||

Table 7: Quality of life among study groups.

Figure 3: Satisfaction on prosthesis characteristics among participants (N=20).

Discussion

For the first time in the literature, amputee patients were compared in terms of prosthesis usage, QoL and independent ambulation abilities. Participants in the prosthesis group performed better in the almost all evaluation categories. Several criteria, including as comfort, aesthetics, weight, and utility, are critical when using a prosthesis in an amputee patient [22,23]. Prostheses also increase QoL by restoring normal body image and enhancing physical ability [24]. Lower limb amputation patients face a variety of physical, psychological, and social issues. The prosthesis group had considerably superior physical function, role physical, and role emotional ratings. We believe that these disparities are due to the fact that the majority of participants in the prosthesis amputee group are far more active and driven in their lives than the patients in the amputee group. As earlier studies have found only lower SF-36 scores in amputee (vs. normal) people in general [25-27], our findings (which are much lower in bilateral amputees) are interesting. Furthermore, because QoL values were positively connected with patients' usage of prostheses (which was more common in the prosthesis group), we assume that prosthetics may have contributed to the difference in QoL levels between the two groups (being higher in the prosthesis group). Previous studies in the literature [28,29] indicated the mean distance necessary for 'functional ambulation' and the mean walking speed as 300 m and 1.33 m/sec (range 1.0–1.67 m/sec). According to the research, unilateral amputee patients had greater walking distance and gait speed; nonetheless, their mean values in both groups were within the aforementioned acceptable limits. As a consequence, these findings may reflect that both groups of patients underwent effective surgery and postoperative rehabilitation. Furthermore, it is well recognized that a patient's age influences the outcome of severe lower extremity injuries [30], and the bulk of our patients were previously healthy young military members with strong physical functions. As a result, we believe that these premorbid characteristics influenced the functional outcome of our patients in each group. Lower limb traumatic amputation patients face a variety of physical and mental issues related to body image, self- care tasks, mobility, and vocational or non-occupational activities [29]. Similarly, past research have focused on comparing amputees to healthy/salvage subjects2-4 or amputees with varied amputation degrees. However, there is insufficient evidence to compare prosthesis use vs. amputations.

Conclusion

To summarize, based on our early data, we infer that the physical capacities of amputee patients are poorer than those of prosthesis amputees. Furthermore, prosthesis satisfaction and body image do not appear to vary with amputation degree, although QoL and contentment with prostheses do grow in tandem with prosthetic use. Finally, we feel that larger-scale research with a bigger patient population is required to examine other characteristics such as energy expenditure index or social status of unilateral vs. bilateral amputee patients.

Budget, Fund or Grant

Research is self-funded.

References

- Knežević A, Salamon T, Milankov M, et al. Assessment of quality of life in patients after lower limb amputation. Med Pregl 2015; 68:103-108.

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1232102-overview

- Jadeja B, Zafer A, Jindal R, et al. Profile of lower limb amputees attended at a tertiary care hospital: A descriptive study. Int Multispecialty J Health 2016; 1:18-25.

- https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED367122

- Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, et al. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: Assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79:931-938.

- Hussain MA, Al-Omran M, Salata K, et al. Population-based secular trends in lower-extremity amputation for diabetes and peripheral artery disease. CMAJ 2019; 191:E955-61.

- Alzahrani HA. Diabetes-related lower extremities amputations in Saudi Arabia: the magnitude of the problem. Annals Vasc Dis 2012; 1204160115.

- Badri MM, Tashkandi WA, Aldaqal SM, et al. Extremities amputations in King Abdulaziz University Hospital (2005-2009). JKAU Med Sci 2011; 18:13-25.

- Musa IR, Ahmed MO, Sabir EI, et al. Factors associated with amputation among patients with diabetic foot ulcers in a Saudi population. BMC Res Notes 2018; 11:1-5.

- Darter BJ, Hawley CE, Armstrong AJ, et al. Factors influencing functional outcomes and return-to-work after amputation: A review of the literature. J Occup Rehab 2018; 28:656-665.

- van der Schans CP, Geertzen JH, Schoppen T, et al. Phantom pain and health-related quality of life in lower limb amputees. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002; 24:429-436.

- Fisher K, Hanspal RS, Marks L. Return to work after lower limb amputation. Int J Rehabil Res 2003; 26:51-56.

- MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Kellam JF, et al. Early predictors of long-term work disability after major limb trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2006; 61:688-694.

- Hewson A, Dent S, Sawers A. Strength deficits in lower limb prosthesis users: A scoping review. Prosthet Orthot Int 2020; 44:323-340.

- Naidoo U, Ennion L. Barriers and facilitators to utilisation of rehabilitation services amongst persons with lower-limb amputations in a rural community in South Africa. Prosthet Orthot Int 2019; 43:95-103.

- Ennion L, Johannesson A. A qualitative study of the challenges of providing pre-prosthetic rehabilitation in rural South Africa. Prosthet Orthot Int 2018; 42:179-186.

- Davie-Smith F, Coulter E, Kennon B, et al. Factors influencing quality of life following lower limb amputation for peripheral arterial occlusive disease: A systematic review of the literature. Prosthet Orthot Int 2017; 41:537-547.

- Järnhammer A, Andersson B, Wagle PR, et al. Living as a person using a lower-limb prosthesis in Nepal. Disabil Rehabil 2018; 40:1426-1433.

- Whoqol Group. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med 1995; 41:1403-1409.

- Pezzin LE, Dillingham TR, MacKenzie EJ, et al. Use and satisfaction with prosthetic limb devices and related services. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85:723-729.

- Srivastava K, Chaudhury S. Rehabilitation after amputation: Psychotherapeutic intervention module in Indian scenario. Scient World J 2014; 2014.

- Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, et al. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: Assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehab 1998; 79:931-938.

- Desmond DM, MacLachlan M. Factor structure of the trinity amputation and prosthesis experience scales (TAPES) with individuals with acquired upper limb amputations. Am J Phys Med Rehab 2005; 84:506-513.

- Pezzin LE, Dillingham TR, MacKenzie EJ. Rehabilitation and the long-term outcomes of persons with trauma-related amputations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81:292-300.

- Weisman IM, Zeballos RJ. Clinical exercise testing. Clin Chest Med 2001; 22:679-701.

- Datta D, Ariyaratnam R, Hilton S. Timed walking test—an all-embracing outcome measure for lower-limb amputees?. Clin Rehab 1996; 10:227-232.

- Smith DG. Amputations. In: Skinner BH (Ed.). Current diagnosis and treatment in orthopaedics. California: Lange, 2005.

- Akarsu S, Tekin L, Safaz I, et al. Quality of life and functionality after lower limb amputations: comparison between uni-vs. bilateral amputee patients. Prosthet Orthot Int 2013; 37:9-13.

- Eftekhari N. Amputation rehabilitation: In: O’Young B, Young MA, Stiens SA (Eds). PMR secrets. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 1999; 214–222.

- Demirsoy C. The MOS-SF-36 health survey: A validation study with a Turkish sample. Master’s Thesis, University of Bosphorus, Turkey, 1999.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Author Info

Bayan Foaud Mogharbe* and Areej Taher Bensadek

Consultant Community and Preventive Medicine, Consultant Infection Control, IPC Certified CBAHI Surveyor, Examiner Member in Saudi Commission, Saudi ArabiaReceived: 22-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-67319; , Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-67319 (PQ); Editor assigned: 24-Jun-2022, Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-67319 (PQ); Reviewed: 11-Jul-2022, QC No. JRMDS-22-67319; Revised: 15-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-67319 (R); Published: 22-Jul-2022