Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 9

The Perception of self and others among students with Depression and Anxiety: A Cross-Sectional Study

Naseem Hafeez Malik1*, Ateeqa Ahmad2, Mahwash Saleem Khan3, Tallat Anwar Faridi4, Muhammad Baqir Hussain5 and Bismah Ahmad6

*Correspondence: Naseem Hafeez Malik, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Psychiatry, University College of Medicine & Dentistry, the University of Lahore, Pakistan, Email:

Abstract

Objective: The research aimed at studying the differences in the perception of anxious and depressed university students. It was hypothesized that depressed students will have more dysfunctional attitudes as compared to anxious students. It was further assumed that students with depression will comparatively have more negative perception of themselves and others associated with them. Material and Methods: The sample comprised of 100 participants, selected from various departments of University of Karachi. They were provided with the Intensive Care Psychological Assessment Tool (IPAT) Anxiety, IPAT Depression scales and (Form B) Dysfunctional Aptitude scale (DAS) as well as a set of personality traits. An adjective checklist of 88 traits was adapted from Neuroticism, Extraversion and Openness Personality Inventory revised (NEO-PI-R). The pattern of responses was illustrated through the use of percentages while the results were analyzed using Chi-square and t-test. Results: The results suggest that no significant difference exists between the perception of self and others among students with depression and anxiety. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed among both groups in DAS scores.

Keywords

Dysfunctional attitude, IPAT depression and anxiety scales, DAS scale

Introduction

Depression is one of the most prevalent types of psychological ailment individuals are exposed to in their life time [1]. The prevalence of depression can be attributed to the biological factors as well as considered to be an outcome of the psychosocial dynamics which affect the mood and life experiences of an individual. Regardless of the debate of what causes depression, it tends to create disruption in the overall functioning of individual creating difficulties in social, interpersonal, academic and professional functioning suggested in the study of prevalence and functional correlates of normative versus idiographic cognitive impairment [2]. It also has an effect on the way an individual perceives their own self. Researchers have asserted in the study of the roles of self-esteem instability and interpersonal sexual objectification, that the perception of individuals dealing with depression is based on the presumption that the individual has low level of competence. As a result, the issues of low self-worth and poor self-esteem also surface [3]. There is also a possibility that the people experiencing depression would devalue their own self while regarding others as having a higher level of social, personal or professional competence.

Studies have found that adolescents are also exposed to the risk of depression among the population [4]. Some of the reasons of depression could be the changes occurring in their psychosocial surroundings as well as the heightened focus on attaining freedom and personal growth [5,6]. It has been further suggested that the occurrence of depression didn’t have any significant differences based on the gender of an individual [7]. Moreover, the authors have also outlined the key dimensions of depression in adolescents comprising dependency, self-criticism and inefficacy [8]. The aspect of bullying has also been highlighted as a contributory factor in development of depression and anxiety among the adolescents [9,10]. Therefore, it can be stated that the causes of depression comprise of both domains, individual and psychosocial factors.

The combination of these factors can result in the experience of depression among adolescence, primarily the sense of dependency and tendency to criticize own self. Other researchers have also found the linkages between the variable of dependency and the occurrence of depression among individuals in the study of attachment styles and suicide-related behaviors in adolescence: the mediating role of self-criticism and dependency [11]. In addition to this, the high degree of criticism directed towards oneself can also increase the chances of developing depression related symptoms [12].

The notion of negative cognitive triad has also been emphasized which proposed that the individuals dealing with depression have a tendency to experience frequent thoughts about being unworthy. Along with that, these negative thoughts also shape their perception about the world in generic terms as well as produce a hopeless outlook of their future prospects [13]. Considering this background, there is a possibility that the perception depressed people have towards others might not depict the similar positive themes. Nevertheless, there have been studies which concluded that the perception of depressed individuals was more positive for others in comparison to their own self.

The problem of anxiety on the other hand has a different set of symptoms and influence on the functioning of an individual. It is marked by excessive worry and apprehension which effects the perception of people [14]. Individuals experiencing anxiety regard the external environment as being a source of threat and regard their own selves as incapable of handling these threats. Anxiety can also have significant effect on the degree of social interaction maintained by an individual. Individuals with high level of anxiety may avoid situations where they are required to interact with others [15]. The primary reason for such avoidant behavior is that they feel high degree of apprehension when placed in a socially stimulating environment which is caused by excessive worry about others regarding them with disdainful attitude. Such negative expectations can in turn harm their competence to handle social interactions in an effective manner [16].

The current research aims to study the differences in the perception of self and others among individuals who are depressed and anxious. It was assumed that depressed individuals will have significantly more negative perception of self as compared to anxious individuals.

It was also hypothesized that depressed and anxious individuals will depict differences in their perception of others. The depressed individuals were assumed to hold significantly more negative attitude as compared to anxious individuals.

Material and Methods

Sample

The sample was selected on the basis of convenience sampling after taking written consent from the participants. Initially 100 questionnaires Intensive Care Psychological Assessment Tool (IPAT) for depression, Intensive Care Psychological Assessment Tool (IPAT) for anxiety and Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DAS) were distributed among the different departments of Karachi University including Psychology, Sociology, Mass communication, Education and Economics. Filling in of these questionnaires by initial 100 students resulted in the identification of 22 students as depressed and 11 students as anxious. The data collection process was repeated, distributing more questionnaires, until a data of 50 depressed and 50 anxious individuals was collected.

The DAS is a 42-item self-report instrument designed to measure the three related negative emotional states of depression, anxiety and tension/stress. The IPAT is reliable and valid tool which investigates for free anxiety level strictly with very little assessment time to each examinee. IPAT anxiety 40 items scale facilitates research for measuring anxiety levels in adults and young adults. The test is in questionnaire form, is practically selfadministering and takes only five-to-ten minutes. The IPAT Depression Scale is a 40-item, paper-and-pencil self-rating depression questionnaire.

IPAT depression and IPAT anxiety was given to the respondents initially. Once the participants were identified as depressed or anxious, they were contacted again for the purpose of collecting data through dysfunctional attitude scale and NEO-PI-R adjectives checklist. The final sample included 10 males and 90 females in the age range was 18-25 years.

Following instruments were used for the assessment of the participants:

IPAT Depression Scale was used to assess the level of depression among the participants. Students scoring high on this scale confessed to be in a depressive mood most of the time. They were burdened by sadness, feelings of inferiority and poor self-image. Those scoring low were found to be more self-confident and adjusted to coping with problems.

IPAT Anxiety Scale (Self Analysis Form) was used to assess the level of anxiety in the participants. Person scoring high on this scale had all the traits of anxiousness. They were burdened by fears and apprehensions, were emotionally unstable, tensed and worried a lot.

Dysfunctional Attitude Scale was used to assess the dysfunctional attitudes of the participants, towards themselves and others. The Form B of DAS was used which consisted of 40 items. The higher the score on DAS the higher the dysfunctional attitudes.

An adjective checklist of 88 items was adapted to select 10 traits out of the list of 88 traits from Neuroticism, Extraversion and Openness Personality Inventory revised (NEO-PI-R).

Results

To evaluate the data, Chi-square and t-test was applied. The results of the study are presented in the tables. The summery of the Table 1 reveals that there is no significant difference in the perception of self, and perception of others among depressed and anxious students. Table 2 also indicates that there is some but not significant difference in perception of self and others by depressed and anxious students. They also show no significant difference between the dysfunctional attitudes of both groups.

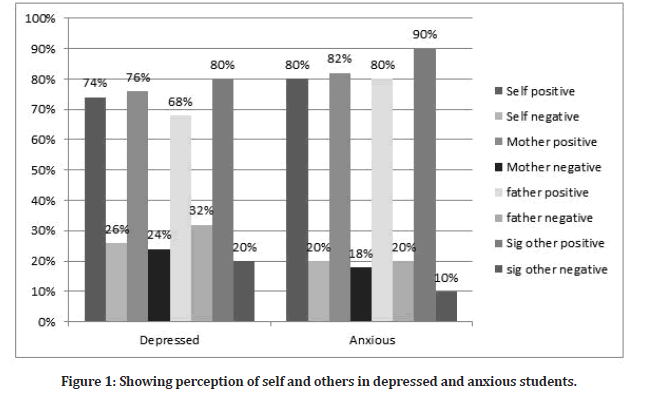

The results of the study are presented in the following tables (Tables 1-3) (Figure 1).

| Perception | Groups | Positive Perceptions | Negative perception | χ 2 | Level of Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self | DEP | 37 | 13 | 0.506 | Not Significant (N.S) |

| ANX | 40 | 10 | |||

| Mother | DEP | 38 | 12 | 0.55 | N.S |

| ANX | 41 | 9 | |||

| Father | DEP | 34 | 16 | 1.927 | N.S |

| ANX | 40 | 10 | |||

| Sig. Other | DEP | 40 | 10 | 2.169 | N.S |

| ANX | 45 | 5 | |||

| Note. χ2=chi-square | |||||

| The summary of the above table reveals that there is no significant difference in the perception of self, and perception of others among depressed and anxious students | |||||

Table 1: Summary of the chi-square test showing perception of self and others of depressed and anxious students (N=100).

| Groups | Self | Mother | Father | Others | M | SD | SE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +ve | -ve | +ve | -ve | +ve | -ve | +ve | -ve | ||||

| Depressed | 74% | 26% | 76% | 24% | 68% | 32% | 80% | 20% | 162.1 | 23.2197 | 3.2838 |

| Anxious | 80% | 20% | 82% | 18% | 80% | 20% | 90% | 10% | 147.84 | 26.2339 | 3.71 |

| Note. Others = represent other relatives and close friends, SE= standard error | |||||||||||

| Table also indicates that there is some but not significant P > 0.05 difference in the perception of self and perception of others by depressed and anxious students. | |||||||||||

Table 2: Percentages showing the difference in the perception of self and others by depressed and anxious students (N=100).

| Levine’s Test For Equality of Variance | T-test for equality of mean | 90% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig | t | Df | Sig (2 tailed) | Mean difference | SE | LL | UL | |

| DAS Equal Variance assumed | 0.822 | 0.367 | 2.878 | 98 | 0.05 | 14.26 | 4.9545 | 4.4279 | 24.0921 |

| DAS Equal Variance not assumed | 2.878 | 96.57 | 0.05 | 14.26 | 4.9545 | 4.4261 | 24.0939 | ||

| Note. CI= Confidence Interval, LL= Lower Limit, UL= Upper Limit | |||||||||

| The above table shows no significant difference between the dysfunctional aptitudes of both groups. | |||||||||

Table 3: Difference in the DAS of depressed and anxious students (N=100).

Figure 1: Showing perception of self and others in depressed and anxious students.

Discussion

It was hypothesized that depressed students will have significantly more negative perception of self as compared to the anxious students. It was also assumed that there will be a difference in the perception of others in depressed and anxious students. Another key hypothesis in the study was that depressed students will have significantly more dysfunctional attitudes as compared to the anxious students; but the results of this study were on the contrary.

It was found that there was no significant difference in the self-perception and perception of others. Similar result of no significant difference was found in the perception of others including mother, father and significant others among depressed and anxious students.

Although other researches support in their studies of self-processing in relation to emotion and reward processing in depression further self‐referential processing and emotion context insensitivity in major depressive disorder, that negative self-perception in depressed individuals [17,18] the current study didn’t demonstrate similar observations. Hypersensitiveness in depressed individuals manifested in the view of their own selves as having low worth is one the major cause of depression [19,20].

A control group (with no significant depression and anxiety symptoms), experimental group 1 (with psychological problems) and experimental group 2 (clinically depressed group), was selected for research purpose to rate themselves according to the series of words presented to them for their reflection. The depressed group remembered more negative words of the series later on during recall as they already perceived them to be self-descriptive than other two groups. Study on interpretation of ambiguity in depression and another study about self-referential processing in the adolescent brain also indicate that more attention is given to the negative part of information than positive in depressed individuals about themselves [21-23].

Percentages, depressed individuals were found to have significantly more dysfunctional attitude than anxious individuals. Emotional disturbance and level of motivation are the result of negative thoughts, which we can regard as the dysfunctional attitude of a person [24,25]. Negative thinking leads to depression due to preoccupation of personal shortcoming and sensitive approach is exhibited in perceiving oneself in a worthless way [26]. One of the numerous studies on perceiving the self and emotions with an anxious mind have collected data on negative thoughts, life stress and symptoms of depression to test the hereditary predispositions of stress at cognition level [27].

In general, it was found that some of the depressed students had experienced stressful life events, but most depressed individuals reported both negative thoughts and stressful life events. For instance, individuals who have a history of stressful experiences including unemployment, low income, relationship problems, any physical disadvantage or loss tend to perceive world as negative and cruel in the absence of adequate resilience power to get through it all. It appears that the perception of the world to deal and survive may heighten the impact of stress and thereby result in depression. This notion has been supported by other studies as well, where it was found that experiencing negative life events increases the likelihood of experiencing depression [28]. Moreover, stress arising out of the continued exposure to negative life events is regarded as one of the causes of depression [29]. The current study findings are quite a unique perspective of indifference for negative self-perception and perception of others among students with depression and anxiety. Despite the fact of the previous findings for the negative selfperception and others among depressed and anxious students; the current study findings would help change the perspective of practitioners. Findings from this work provide new insights into the ways during clinical practice for the indifference particular between the negative self-perception and negative perception of others with the manifestation of anxiety and depression symptoms among students.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that the possibility of perceptual differences towards self and others may not be significant. Previous studies emphasized the presence of negative perception among the depressed individuals. However, this study presents contrary evidence, suggesting that such inferences do not seem to be applicable to university students. Case in point, the investigators and clinicians should take care of the different perspective acclimatized to negative perception about self and others may not be a defining feature of depression and anxiety among selected population. Further, our findings add to the ever increasing range of literature investigating the individual and contextual factors salutary to the expression of the anxiety and depression symptoms with regards to perception of self and others as well as in general. Moreover the results open up the path for future exploration.

IPAT depression and IPAT anxiety were used to screen the students as depressed and anxious. Other diagnostic tests for identifying depression and anxiety could support in deriving further inferences. This study indicates an interesting phenomenon, in the form of absence of the strong negative perception which was assumed to be present among depressed and anxious students.

Limitations of the Study

The limitations of the research include the sample comprising adolescents, and the cross sectional design. Future researchers can conduct comparative analysis between depressed and anxious young adults (age 18 to 25) and adults (26 to 40 years) to identify differences existing in perception of these groups. Moreover, a longitudinal approach can be adopted to examine the changes occurring in the perception of depressed and anxious individuals over time. Furthermore, individuals who have received diagnosis of depression and anxiety can be selected as a part of the study to examine their perception towards self and others.

References

- Shorey S, Ng ED, Wong CH. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Clin Psychol 2022; 61:287-305.

- Tran T, Milanovic M, Holshausen K, et al. What is normal cognition in depression? Prevalence and functional correlates of normative versus idiographic cognitive impairment. Neuropsychol 2021; 35:33.

- Ching BH, Wu HX, Chen TT. Body weight contingent self-worth predicts depression in adolescent girls: The roles of self-esteem instability and interpersonal sexual objectification. Body Image 2021; 36:74-83.

- Clayborne ZM, Varin M, Colman I. Systematic review and meta-analysis: adolescent depression and long-term psychosocial outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019; 58:72-79.

- Chi X, Liu X, Huang Q, et al. Depressive symptoms among junior high school students in southern China: prevalence, changes, and psychosocial correlates. J Affect Disord 2020; 274:1191-200.

- Kırcaburun K, Kokkinos CM, Demetrovics Z, et al. Problematic online behaviors among adolescents and emerging adults: Associations between cyberbullying perpetration, problematic social media use, and psychosocial factors. Int J Ment Health Addict 2019; 17:891-908.

- Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psycho Bulletin 2017; 143:783.

- Petrocchi N, Dentale F, Gilbert P. Self‐reassurance, not self‐esteem, serves as a buffer between self‐criticism and depressive symptoms. Psychol Psychother Ther Res Prac 2019; 92:394-406.

- Vergara GA, Stewart JG, Cosby EA, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury and suicide in depressed adolescents: Impact of peer victimization and bullying. J Affect Disord 2019; 245:744-749.

- Choi JK, Teshome T, Smith J. Neighborhood disadvantage, childhood adversity, bullying victimization, and adolescent depression: A multiple mediational analysis. J Affect Disord 2021; 279:554-562.

- Falgares G, Marchetti D, De Santis S, et al. Attachment styles and suicide-related behaviors in adolescence: the mediating role of self-criticism and dependency. Front Psychiatr 2017; 8:36.

- Aruta JJ, Antazo B, Briones-Diato A, et al. When does self-criticism lead to depression in collectivistic context. Int J Adv Counsel 2021; 43:76-87.

- Larson R, Asmussen L. Anger, worry, and hurt in early adolescence: An enlarging world of negative emotions. In Adolescent stress 2017; 21-42.

- Adrian M, Jenness JL, Kuehn KS, et al. Emotion regulation processes linking peer victimization to anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescence. Dev Psychopathol 2019; 31:999-1009.

- Gazelle H, Rubin KH. Social withdrawal and anxiety in childhood and adolescence: Interaction between individual tendencies and interpersonal learning mechanisms in development. J Abnormal Child Psychol 2019; 47:1101-1106.

- Charmaraman L, Richer AM, Liu C, et al. Early adolescent social media-related body dissatisfaction: Associations with depressive symptoms, social anxiety, peers, and celebrities. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2021; 42:401.

- Hobbs C, Sui J, Kessler D, et al. Self-processing in relation to emotion and reward processing in depression. Psychol Med 2021; 1-3.

- McIvor L, Sui J, Malhotra T, et al. Self‐referential processing and emotion context insensitivity in major depressive disorder. Eur J Neurosci 2021; 53:311-329.

- Calin MF, Sandu ML, Zburlea A. Identifying the relationships between personality and behavior in adolescents. Technium Soc Sci J 2021; 20:546.

- Dudley AI. Multiracial young adults, perceived racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, identity integration, and race-based rejection sensitivity: Testing a moderated mediation model.. Doctoral dissertation, University of South Alabama, 2021.

- Butterfield RD. Self-Referential processing in the adolescent brain: do neural self-referential processes related to adolescent self-concept confer risk for depression? Doctoral dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, 2021.

- Everaert J. Interpretation of ambiguity in depression. Curr Opin Psychol 2021; 41:9-14.

- Scherr S, Arendt F, Prieler M, et al. Investigating the negative-cognitive-triad-hypothesis of news choice in Germany and South Korea: Does depression predict selective exposure to negative news?. Social Sci J 2021; 1-8.

- Perez J, Rohan KJ. Cognitive predictors of depressive symptoms: Cognitive reactivity, mood reactivity, and dysfunctional attitudes. Cognit Ther Res 2021; 45:123-135.

- Schweizer TH, Snyder HR, Young JF, et al. Prospective prediction of depression and anxiety by integrating negative emotionality and cognitive vulnerabilities in children and adolescents. Res Child Adolescent Psychopathol 2021; 49:1607-1621.

- McIvor L, Sui J, Malhotra T, et al. Self‐referential processing and emotion context insensitivity in major depressive disorder. Eur J Neurosci 2021; 53:311-329.

- Feldborg M, Lee NA, Hung K, et al. Perceiving the self and emotions with an anxious mind: Evidence from an implicit perceptual task. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18:12096.

- Pössel P, Burton SM, Cauley B, et al. Associations between social support from family, friends, and teachers and depressive symptoms in adolescents. J Youth Adolesc 2018; 47:398-412.

- Hosseini A, Jalali M. The possible biological effects of long-term stress on depression. Medbiotech J 2018; 2:149-152.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Author Info

Naseem Hafeez Malik1*, Ateeqa Ahmad2, Mahwash Saleem Khan3, Tallat Anwar Faridi4, Muhammad Baqir Hussain5 and Bismah Ahmad6

1Department of Behavioral Sciences and Psychiatry, University College of Medicine & Dentistry, the University of Lahore, Pakistan2Clinical Psychologist, Scholar at University of Management and Technology Lahore, Pakistan

3Senior Lecturer, Lahore Medical College, Pakistan

4Assistant Professor, University Institute of Public Health, the University of Lahore, Pakistan

5Horizon Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan

6Department of Oral Pathology, Lahore Medical College, Pakistan

Received: 11-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. jrmds-22-54092; , Pre QC No. jrmds-22-54092(PQ); Editor assigned: 13-Aug-2022, Pre QC No. jrmds-22-54092(PQ); Reviewed: 29-Aug-2022, QC No. jrmds-22-54092(Q); Revised: 02-Sep-2022, Manuscript No. jrmds-22-54092(R); Published: 09-Sep-2022