Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 11

The Effect of Work Conditions on the Perceived Quality of Care among Nurses Working in Hemodialysis Centers in Asser Region, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-sectional Study

Shaaban Nasser Al Shawan1*, Bayapa Reddy Narapureddy2, Fayez Mari Alamri3 and Khalid Nasser Al Shawan4

*Correspondence: Shaaban Nasser Al Shawan, Nursing specialist, Rejal Almaa general Hospital, Ministry of Health, KSA, Email:

Abstract

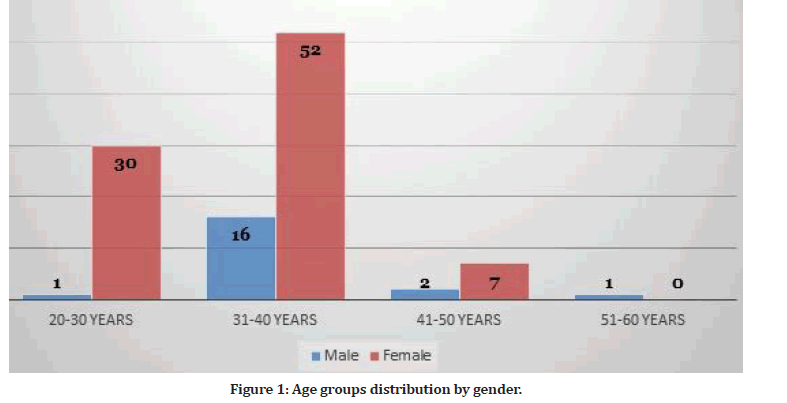

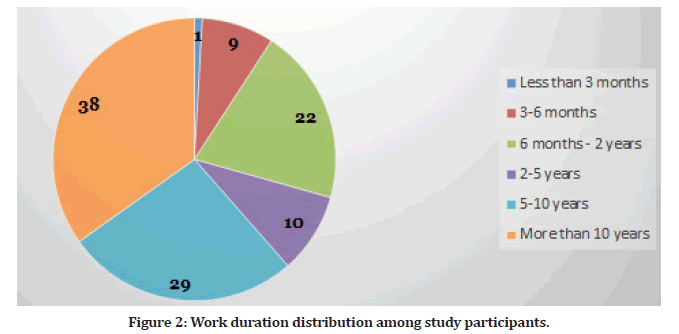

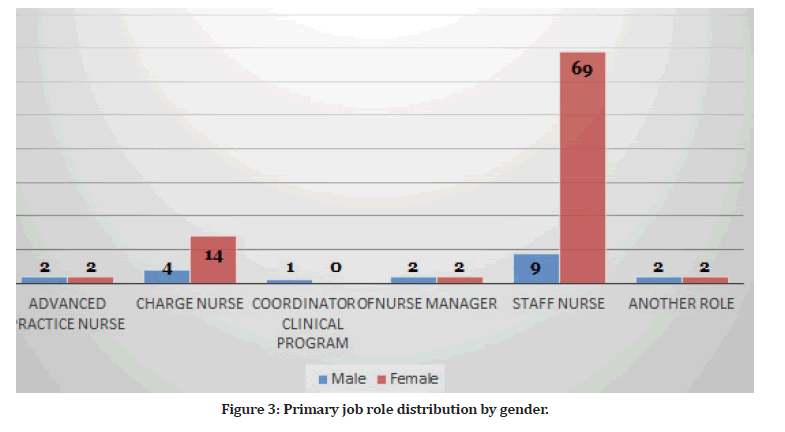

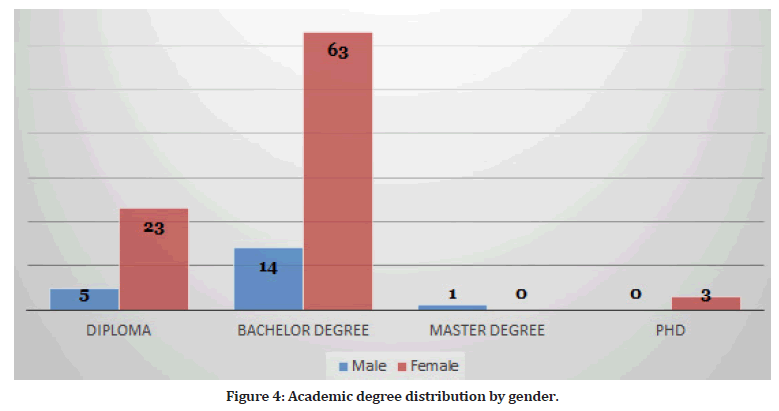

In a technologically complicated work environment, hemodialysis nurses build long-term connections with patients. Previous research has shown that hemodialysis nurses encounter pressures connected to the nature of their employment as well as their work settings, resulting in significant degrees of burnout. For this purpose, a cross-sectional analytical descriptive study was performed among hemodialysis nurses at Aseer Regions. The current study included 109 participants. Among them, there were 89 females (81.7%) and 20 males (18.3%). The most frequent age group was 31-40 years (n=68, 62.4%). The study included 69 Saudi participants (63.3%) and 40 non-Saudi participants (36.7%). The current job status for study participants was full-time among 101 participants (92.7%), part-time among 5 participants (4.6%), and another job status among 3 participants (2.8%). The most frequent duration of working experience was more than 10 years (n=38, 34.9%). The most frequent primary role among study participants was staff nurse (n=78, 71.6%) while the highest university degree was Ph.D. among 3 participants (2.8%) while the most frequent academic degree was bachelor's degree (n=77, 70.6%). Overall the work environment was perceived positively and there was a moderate level of job satisfaction. However, levels of stress and emotional exhaustion (burnout) were high. Nurse Managers can use these results to identify issues being experienced by hemodialysis nurses working in the unit they are supervising.

Keywords

Hemodialysis, Chronic kidney disease, Renal replacement therapy, End stage renal disease

Introduction

Hemodialysis (HD) is a kidney replacement therapy that aims to maintain patients in good health and improve their quality of life while they wait for a transplant or suffer horribly. To offer effective treatment to these patients, health professionals and the patient's family must work together [1]. The nursing staff is the axis of in-hospital care that connects the many acts required to give comprehensive care to HD patients. The HD unit nurses are in charge of assessing the patient's numerous requirements and integrating and arranging care during substitution therapy to ensure that it is delivered with quality, warmth, and efficacy. The many responsibilities that nursing professionals in HD units must perform, such as care technology expert, specialist caregiver, educator, facilitator, and emotional counselor, make their job difficult. Their job is to combine these positions to build a unique therapeutic connection with each patient, which is a difficult endeavor. Working factors, such as hospital infrastructure, human resources, service organization, number of patients, and shifts worked, all impact the process of nursing care for renal patients on hemodialysis. All of the mentioned issues make nursing care in HD units more demanding than in other areas of hospital care, and they can inflict wear and tear on the nursing staff, mostly due to stress, feelings of powerlessness, and incompetence [2]. Various studies have looked into the impacts of nursing professionals working in HD units; some claim that the staff of these units is subjected to significant pressures in the workplace, mostly due to difficult jobs and patient circumstances, resulting in varying levels of burnout. According to several researches, the work environment in HD units is particularly tough, hectic, and stressful, because providing complete care necessitates a high degree of expertise and knowledge on the part of the nurses [3].

It is critical to understand the nurses' perspectives on their satisfaction with the work environment, stressful elements, and those that might cause tiredness and frustration to enhance the quality of nursing care for HD patients in technical, emotional, and spiritual aspects. Aspects have received little attention in Saudi Arabia, particularly from the perspective of quantitative research. The goal of this study was to determine the work characteristics, job satisfaction, job stress, and burnout of nursing professionals in hemodialysis units in the Asser area of Saudi Arabia, as well as the link between them and their impact on care quality.

Problem statement

Overview

One of the main challenges of care is the complexity of the condition of kidney patients. They are patients in a delicate or serious condition who are treated on an outpatient basis and present particular characteristics given that they face multiple dysfunctions and a deterioration that is accentuated rapidly and considerably affects their physical, emotional, and social state. This makes it particularly difficult for nursing staff to meet the specific needs and demands of patients, which complicates care. So, we will determine the characteristics of work environment, job satisfaction, job stress, and burnout degree among nurses at HD units, to provide an applicable solution to improve the quality of care for HD patients.

Research question/hypothesis

What are the characteristics of the nursing work environment at hemodialysis units, in the Asser region, KSA?

What is the level of job satisfaction among hemodialysis unit nurses, in the Asser region, KSA?

What is the level of nursing stress in hemodialysis units, in the Asser region, KSA?

What is the prevalence of burnout among hemodialysis unit nurses?

Relevance/rationale

Reduced glomerular filtration is a hallmark of chronic kidney disease (CKD), which is commonly associated with conditions like diabetes and hypertension. It is a condition that affects around 10% of the world's population and that may be treated with renal replacement therapy (RRT) in three distinct ways: hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation in the most severe instances [4]. In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a severe health problem. In 2021, there will be approximately 20,000 dialysis patients in Saudi Arabia, with 9,810 patients receiving kidney transplant followup. The combined prevalence of RRT in Saudi Arabia is estimated at 294.3 per million population [5]. Although complications during hemodialysis sessions are minimal, some are exceedingly serious and deadly. The nursing staff plays a critical role in the constant monitoring of patients during the session, which can save many lives and prevent numerous problems when such issues are detected early. The patient should have complete faith in the expert nurses who are always on the lookout for opportunities to intervene [6].

Here, we will approach the nurses' practice, work environment characteristics, job satisfaction, job stress, and burnout; to ensure the best quality of care is provided to HD patients in Saudi Arabia, and the Asser region specifically.

Background and significance

In the United States, about 500,000 people with endstage renal disease (ESRD) use hemodialysis as a renal replacement treatment, with 98 percent getting it in outpatient dialysis centers. Even though hemodialysis has evolved from an unusual to a routine procedure in the last 50 years, hemodialysis centers might be particularly dangerous for patients. Several care professionals, innovative technology, and multiple patients with substantial comorbidities are all involved in hemodialysis treatment facilities. In hemodialysis units, possible safety risk areas include water quality, dialyzer reuse, infection management, intradialytic hypotension, vascular access difficulties, medication mistakes, and miscommunications among staff members and with patients. Patient safety is a critical component of highquality treatment, and developing a safety culture in hemodialysis units is critical for decreasing patient risks of injury, preventing or reducing mistakes, and increasing the quality of care provided. A commitment at all levels of the organization, from frontline providers to managers and executives, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), to minimize adverse patient events in the face of inherently complex and potentially hazardous procedures, such as hemodialysis treatments [3].

Knowing the workload of nurses in hemodialysis units enables improved human resource management. Determine the workload of nurses based on the dependency and risk profiles of chronic hemodialysis patients. In this study, 151 patients were chosen from five hemodialysis units and classified according to their reliance and risk using the "Care according to Dependence and Risk in Hemodialysis" tool (CUDYRDIAL). Nurses' direct and indirect care actions, as well as the time it took them to accomplish them, were tracked. Nurses spent an average of 36.5 minutes on direct care and 23.6 minutes on indirect care for each patient. Direct care time was 41.2 minutes for patients at high risk with partial reliance and 40.3 minutes for patients at high risk with partial self-sufficiency, respectively. During a dialysis session, nurses spend 60% of their time providing direct care, particularly to patients at risk of partial dependency or self-sufficiency [7].

Furthermore, the goal of this study was to report nurses' experiences with hemodialysis care. Purposive sampling began in this phenomenological investigation and continued until data saturation. The Hemodialysis unit served as the research setting. Semi-structured interviews were used to gather information. There were two primary classes and four sub-classes found, covering elements that affect care (inhibitors and facilitators) and care outcomes (bad impacts of care on the nurse and good effects of care on the patient), as well as the overarching subject of "difficult care.". As the findings reveal, nurses experience a variety of physical and emotional suffering, which extends to their home environment, and their families are impacted indirectly by the negative impacts of their care. As a result, enhancing management tactics to reduce inhibitor factors is critical in preventing nurse burnout or quitting while also increasing the quality of care they give [8].

Another study looked at the barriers and challenges of hemodialysis nursing care; the findings revealed that to make hemodialysis care more efficient, it is necessary to hire efficient human resources and nurses who can establish close relationships with patients, have basic knowledge, be able to learn hemodialysis skills, and have enough experience. On the other hand, barriers to hemodialysis care include a shortage of nurses, a heavy workload, the head nurse's lack of authority, an ignorant director of nursing, a shortage of nephrologists, a lack of vascular surgeons, a lack of nurse aide and nursing assistant, unskilled staff, and caregiver interventions. Patients and their families must be provided with guidelines, training, and continuing support from the treatment team so that they may readily deal with and accept lifestyle changes. These treatments can help patients live longer lives and even provide assistance for caretakers [9].

Because of considerable work-related pressures, nephrology nurses confront health and wellness difficulties. The psychological well-being of nephrology nurses in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic (n=393) was measured in an online survey, which was completed between July 24 and August 17, 2020. Respondents said they were burned out at work (62%), had anxiety symptoms (47% with GAD-7 levels of >=5), and had severe depressive episodes (16% with PHQ-2 ratings of >=3). Fifty-six percent (56%) of study respondents said they cared for COVID-19 patients, and 62% said they were concerned about COVID-19 in some way. High workload, age, race, and the COVID-19 pandemic may all have a role in the high number of nephrology nurses reporting burnout, anxiety, and depression [10].

Aims and Objectives

Overall aim

To evaluate the nursing practice at Hemodialysis units, at 4 main levels: work environment perceptions, job satisfaction, job stress, and burnout. To determine the relationships between those aspects on quality of care provided to Hemodialysis patients, in the Asser region, KSA.

Specific objectives

To find out how Hemodialysis nurses in the Asser area of Saudi Arabia feel about their work environment, job satisfaction, job stress, and burnout.

To determine the relationships between Hemodialysis nurses' characteristics and their perceptions of work environment, job satisfaction, job stress, and burnout, in Asser region, KSA.

To assess the quality of care provided by nurses at Hemodialysis units, in the Asser region, KSA.

Study Design and Methods

Study setting and design

A cross-sectional study was implemented in the Asser region, Hemodialysis centers, and KSA. From the period of 1st March-1st May 2022.

Study population and sampling technique

The study population will be all nurses working at the hemodialysis centers at Asser Region, KSA.

The study sample will be collected using the convenient sampling technique.

Sample size calculation

The sample size will be calculated via Epi-Info software [11], at a confidence level of 95% and statistical power of 80%.

Data collection methods and instruments

The data were collected prospectively from the hemodialysis nurses directly, via many ways; printed questionnaires. Online google forms. The data collection tool contains five main sections:

Demographic and work characteristics. There were five sections to the data gathering tool. The demographic and employment aspects were covered in the first part. Gender, nationality, age, length of experience working in the hemodialysis setting, and the nurse-to-patient ratio will be gathered. Nurses were also will be asked about their highest nursing degree and whether or not they had completed any postgraduate training in renal nursing.

The National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators Index 2020 (NDNQI-Index) (Index of Work Satisfaction) [12].

Brisbane Practice Environment Measure (B-PEM) [13].

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [14].

Nursing Stress Scale (NSS) [15].

Data analysis

SPSS version 26 will be used to analyze the data.

Kurtosis and skew analysis will be used to determine the data's normality. To summarize sample characteristics and explain hemodialysis nurses' work conditions, job satisfaction, stress, and burnout, descriptive statistics will be employed. We'll compare means using independent t-tests and ANOVAs to see if nurse traits are linked to work satisfaction, stress, or burnout. Finally, we'll use Pearson's correlation coefficients to investigate the correlations between nurses' work environment, job satisfaction, stress, and burnout. For all analyses, the statistical significance will be defined as p.05.

Ethics and human subjects issues

Ethical approval was obtained from IRB, after submitting the proposal and questionnaire.

Moreover, informed consent was signed by each participant.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This study will be the first one in the KSA, and one of the most recent studies worldwide, which applies the adopted indexes to Hemodialysis nurses. As they are playing an important role when dealing with hemodialysis patients in particular.

However, there will be some challenges during the data collection process. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and recent variants, there will be some restrictions and limitations in reaching out to the targeted nurses during their work, we may overcome this issue by sending the questionnaire online to them.

Results

The current study included 109 participants. Among them, there were 89 females (81.7%) and 20 males (18.3%). The most frequent age group was 31-40 years (n=68, 62.4%) (Figure 1). The study included 69 Saudi participants (63.3%) and 40 non-Saudi participants (36.7%). The current job status for study participants was full-time among 101 participants (92.7%), parttime among 5 participants (4.6%), and another job status among 3 participants (2.8%). The most frequent duration of working experience was more than 10 years (n=38, 34.9%) (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Age groups distribution by gender.

Figure 2: Work duration distribution among study participants.

The most frequent primary role among study participants was staff nurse (n=78, 71.6%) (Figure 3) while the highest university degree was Ph.D. among 3 participants (2.8%) while the most frequent academic degree was bachelor's degree (n=77, 70.6%) (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Primary job role distribution by gender.

Figure 4:Academic degree distribution by gender.

Female participants had higher educational degrees than male participants (P=0.04) as well as higher positions in the job (P=0.034). Work satisfaction among study participants was assessed using the index of work satisfaction questionnaire as shown in the following Table 1.

| Item | Response | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree | ||

| Career development/clinical ladder opportunity | F | 5 | 4 | 13 | 54 | 33 |

| % | 4.6 | 3.7 | 11.9 | 49.5 | 30.3 | |

| Opportunity for staff nurses to participate in policy decision | F | 7 | 4 | 18 | 54 | 26 |

| % | 6.4 | 3.7 | 16.5 | 49.5 | 23.9 | |

| A chief nursing officer which is highly visible and accessible to staff | F | 5 | 2 | 17 | 54 | 31 |

| % | 4.6 | 1.8 | 15.6 | 49.5 | 28.4 | |

| The administration that listens and responds to employee concerns | F | 9 | 6 | 25 | 47 | 22 |

| % | 8.3 | 5.5 | 22.9 | 43.1 | 20.2 | |

| Staff nurses are involved in the internal governance of the hospital | F | 13 | 5 | 24 | 50 | 17 |

| % | 11.9 | 4.6 | 22 | 45.9 | 15.6 | |

| Nursing administrators consult with staff on daily problems and procedures | F | 10 | 8 | 22 | 49 | 20 |

| % | 9.2 | 7.3 | 20.2 | 45 | 18.3 | |

| Active staff development or continuing education programs for nurses | F | 8 | 7 | 19 | 50 | 25 |

| % | 7.3 | 6.4 | 17.4 | 45.9 | 22.9 | |

| High standards of nursing care are expected by the administration | F | 3 | 1 | 18 | 67 | 20 |

| % | 2.8 | 0.9 | 16.5 | 61.5 | 18.3 | |

| A clear philosophy of nursing that pervades the patient care environment | F | 7 | 2 | 30 | 55 | 15 |

| % | 4.6 | 1.8 | 27.5 | 50.5 | 13.8 | |

| Working with nurses who are clinically competent | F | 3 | 3 | 8 | 71 | 24 |

| % | 2.8 | 2.8 | 7.3 | 65.1 | 22 | |

| An active quality assurance program | F | 9 | 3 | 20 | 55 | 22 |

| % | 8.3 | 2.8 | 18.3 | 50.5 | 20.2 | |

| A preceptor program for newly hired RNs | F | 7 | 4 | 12 | 53 | 33 |

| % | 6.4 | 3.7 | 11 | 48.6 | 30.3 | |

| Nursing care is based on nursing, rather than a medical model | F | 5 | 3 | 16 | 65 | 20 |

| % | 4.6 | 2.8 | 14.7 | 59.6 | 18.3 | |

| Written up-to-date nursing care plans for all patients | F | 7 | 2 | 14 | 59 | 27 |

| % | 6.4 | 1.8 | 12.8 | 54.1 | 24.8 | |

| Patient care assignments that foster continuity of care | F | 6 | 2 | 16 | 69 | 16 |

| % | 5.5 | 1.8 | 14.7 | 63.3 | 14.7 | |

| A supervisory staff that is supportive of the nurses | F | 9 | 8 | 21 | 54 | 17 |

| % | 8.3 | 7.3 | 19.3 | 49.5 | 15.6 | |

| Supervisors use mistakes as learning opportunities, not criticism | F | 10 | 9 | 18 | 57 | 15 |

| % | 9.2 | 8.3 | 16.5 | 52.3 | 13.8 | |

| A nurse manager who is a good manager and leader | F | 7 | 5 | 16 | 45 | 27 |

| % | 6.4 | 4.6 | 14.7 | 49.5 | 24.8 | |

| Praise and recognition for a job well done | F | 5 | 6 | 16 | 59 | 23 |

| % | 4.6 | 5.5 | 14.7 | 54.1 | 21.1 | |

| A nurse manager who backs up the nursing staff in decision-making even if the conflict is with a physician | F | 6 | 4 | 20 | 64 | 15 |

| % | 5.5 | 3.7 | 18.3 | 58.7 | 13.8 | |

| Adequate support services allow me to spend time with my patients | F | 9 | 2 | 20 | 61 | 17 |

| % | 8.3 | 1.8 | 18.3 | 56 | 15.6 | |

| Enough time and opportunity to discuss patient care problems with other nurses | F | 13 | 3 | 17 | 58 | 18 |

| % | 11.9 | 2.8 | 15.6 | 53.2 | 16.5 | |

| Enough registered nurses to provide quality patient care | F | 16 | 23 | 15 | 41 | 14 |

| % | 14.7 | 21.1 | 13.8 | 37.6 | 12.8 | |

| Enough staff to get the work done | F | 13 | 18 | 19 | 43 | 16 |

| % | 11.9 | 16.5 | 17.4 | 39.4 | 14.7 | |

| Physicians and nurses have a good working relationships | F | 1 | 2 | 19 | 65 | 22 |

| % | 0.9 | 1.8 | 17.4 | 59.6 | 20.2 | |

| A lot of teamwork between nurses and physicians | F | 9 | 3 | 23 | 57 | 17 |

| % | 8.3 | 2.8 | 21.1 | 52.3 | 15.6 | |

| Collaboration between nurses and physicians | F | 2 | 3 | 22 | 63 | 19 |

| % | 1.8 | 2.8 | 20.2 | 57.8 | 17.4 | |

| RNs I work with count on each other to pitch in and help when things get busy | F | 3 | 1 | 18 | 60 | 27 |

| % | 2.8 | 0.9 | 16.5 | 55 | 24.8 | |

| There is a good deal of teamwork among RNs I work with | F | 4 | 1 | 14 | 61 | 29 |

| % | 3.7 | 0.9 | 12.8 | 56 | 26.6 | |

| RNs I work with support each other | F | 1 | 2 | 18 | 63 | 25 |

| % | 0.9 | 1.8 | 16.5 | 57.8 | 22.9 | |

| As RNs, we are fairly well satisfied with our jobs on our units | F | 3 | 7 | 17 | 56 | 26 |

| % | 2.8 | 6.4 | 15.6 | 51.4 | 23.9 | |

| RNs on our unit would not consider taking another job | F | 12 | 5 | 29 | 50 | 13 |

| % | 11 | 4.6 | 26.6 | 45.9 | 11.9 | |

| I have to force myself to come to work much of the time | F | 20 | 5 | 25 | 45 | 14 |

| % | 18.3 | 4.6 | 22.9 | 41.3 | 12.8 | |

| RNs on our unit are enthusiastic about our work almost every day | F | 11 | 3 | 19 | 57 | 19 |

| % | 10.1 | 2.8 | 17.4 | 52.3 | 17.4 | |

| RNs on our unit like our jobs better than the average RN does | F | 7 | 2 | 21 | 59 | 20 |

| % | 6.4 | 1.8 | 19.3 | 54.1 | 18.3 | |

| I feel that each day on my job will never end | F | 16 | 1 | 30 | 48 | 14 |

| % | 14.7 | 0.9 | 27.5 | 44 | 12.8 | |

| We find real enjoyment in our work on our unit | F | 4 | 4 | 14 | 67 | 20 |

| % | 3.7 | 3.7 | 12.8 | 61.5 | 18.3 | |

Table 1: Participants’ responses to the index of work satisfaction questionnaire.

This study will be the first one in the KSA, and one of the most recent studies worldwide, which applies the adopted indexes to Hemodialysis nurses. As they are playing an important role when dealing with hemodialysis patients in particular (Table 2).

| Variable | F | df B | df W | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 98.93 | 1 | 501 | 0 |

| Age | 4.84 | 3 | 499 | 0.0025 |

| Education | 8.97 | 2 | 500 | 0.0002 |

| Experience | 4.82 | 3 | 499 | 0.0026 |

| Sex | 4.76 | 1 | 501 | 0.0295 |

| Work status | 1.55 | 1 | 501 | 0.2132 |

Table 2: Statistical significant relationships between participants’ characteristics and index of work satisfaction questionnaire.

The vast majority of participants' plans for the next years were to stay in the same job position (n- 59, 54.1%). The main reason for this choice was personal circumstances (n=56, 51.4%). Participants in this study described the quality of care they provide to patients as excellent (n=60, 55%), good (n=43, 39.4%) and fair (n=6, 5.5%). Most participants perceive the number of assigned patients per shift as good and they agree that the number is appropriate (n=53, 48.6%). Most of participants are assigned 2-5 patients per shift (n=77, 70.6%). Conversely, some other participants were assigned more than 10 patients per shift (n=9, 8.3%). The shift working hours ranged from less than 6 hours to more than 12 hours. Participants’ burnout levels were assessed using Maslach Burnout Inventory as presented in Table 3.

| Item | F | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | ||||||||

| I feel emotionally exhausted because of my work | F | 19 | 23 | 20 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 9 |

| % | 17.4 | 21.1 | 18.3 | 11 | 11.9 | 11.9 | 8.3 | |

| I feel worn out at the end of a working day | F | 14 | 14 | 16 | 14 | 20 | 16 | 15 |

| % | 12.8 | 12.8 | 14.7 | 12.8 | 18.3 | 14.7 | 13.8 | |

| I feel tired as soon as I get up in the morning and see a new working day stretched out in front of me | F | 24 | 23 | 13 | 17 | 18 | 6 | 8 |

| % | 22 | 21.1 | 11.9 | 15.6 | 16.5 | 5.5 | 7.3 | |

| I can easily understand the actions of my colleagues/supervisors | F | 10 | 11 | 13 | 12 | 17 | 12 | 34 |

| % | 9.2 | 10.1 | 11.9 | 11 | 15.6 | 11 | 31.2 | |

| I get the feeling that I treat some clients/colleagues impersonally as if they were objects | F | 33 | 19 | 16 | 13 | 17 | 5 | 6 |

| % | 30.3 | 17.4 | 14.7 | 11.9 | 15.6 | 4.6 | 5.5 | |

| Working with people the whole day is stressful for me | F | 7 | 12 | 11 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 29 |

| % | 6.4 | 11 | 10.1 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 18.3 | 26.6 | |

| I deal with other people’s problems successfully | F | 21 | 16 | 14 | 19 | 18 | 10 | 11 |

| % | 19.3 | 14.7 | 12.8 | 17.4 | 16.5 | 9.2 | 10.1 | |

| I feel burned out because of my work | F | 7 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 14 | 21 | 41 |

| % | 6.4 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 7.3 | 12.8 | 19.3 | 37.6 | |

| I feel that I influence other people positively through my work | F | 53 | 9 | 16 | 8 | 11 | 10 | 2 |

| % | 48.6 | 8.3 | 14.7 | 7.3 | 10.1 | 9.2 | 1.8 | |

| I have become more callous to people since I have started doing this job | F | 44 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 20 | 4 | 4 |

| % | 40.4 | 10.1 | 11.9 | 11.9 | 18.3 | 3.7 | 3.7 | |

| I’m afraid that my work makes me emotionally harder | F | 20 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| % | 18.3 | 11 | 8.3 | 7.3 | 17.4 | 18.3 | 19.3 | |

| I feel full of energy | F | 37 | 15 | 18 | 8 | 13 | 8 | 10 |

| % | 33.9 | 13.8 | 16.5 | 7.3 | 11.9 | 7.3 | 9.2 | |

| I feel frustrated by my work | F | 10 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 11 | 16 | 48 |

| % | 9.2 | 9.2 | 7.3 | 5.5 | 10.1 | 14.7 | 44 | |

| I get the feeling that I work too hard | F | 43 | 12 | 14 | 9 | 14 | 7 | 10 |

| % | 39.4 | 11 | 12.8 | 8.3 | 12.8 | 6.4 | 9.2 | |

| I’m not really interested in what is going on with many of my colleagues | F | 31 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 21 | 8 | 9 |

| % | 28.4 | 11.9 | 12.8 | 11.9 | 19.3 | 7.3 | 8.3 | |

| Being in direct contact with people at work is too stressful | F | 11 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 10 | 20 | 30 |

| % | 10.1 | 8.3 | 11.9 | 14.7 | 9.2 | 18.3 | 27.5 | |

| I find it easy to build a relaxed atmosphere in my working environment | F | 9 | 13 | 5 | 14 | 14 | 24 | 30 |

| % | 8.3 | 11.9 | 4.6 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 22 | 27.5 | |

| I feel stimulated when I am working closely with my colleagues | F | 7 | 17 | 10 | 15 | 13 | 20 | 27 |

| % | 6.4 | 15.6 | 9.2 | 13.8 | 11.9 | 18.3 | 24.8 | |

| I have achieved many rewarding objectives in my work | F | 44 | 10 | 25 | 14 | 7 | 3 | 6 |

| % | 40.4 | 9.2 | 22.9 | 12.8 | 6.4 | 2.8 | 5.5 | |

| I feel as if I’m at my wits‘ end | F | 21 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 17 | 13 | 15 |

| % | 19.3 | 13.8 | 11.9 | 13.8 | 15.6 | 11.9 | 13.8 | |

| In my work, I am very relaxed when dealing with emotional problems | F | 46 | 21 | 20 | 7 | 11 | 2 | 2 |

| % | 42.2 | 19.3 | 18.3 | 6.4 | 10.1 | 1.8 | 1.8 | |

| I have the feeling that my colleagues blame me for some of their problems | F | 7 | 17 | 10 | 15 | 13 | 20 | 27 |

| % | 6.4 | 15.6 | 9.2 | 13.8 | 11.9 | 18.3 | 24.8 | |

| 0: Never; 1: At least a few times a year; 2: At least once a month; 3: Several times a month; 4: Once a week; 5: Several times a week; 6: Every day | ||||||||

Table 3: Participants’ responses to the Maslach burnout inventory.

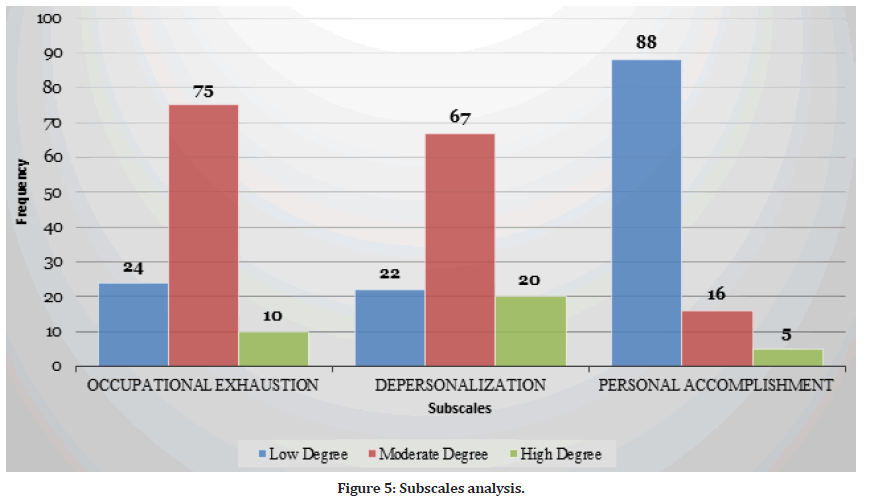

The Maslach Burnout Inventory scale is further subdivided into three subscales, which are occupational exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (loss of empathy) (DP), and personal accomplishment (PA). These subscales are dependent on the sum of some items. Then the total sum is categorized into a low degree, moderated degree, and high degree. Figure 5 shows the participants' results with regard to these three subscales. Participants’ stress levels were assessed using the nursing stress scale as presented in Table 4. Female participants had a higher stress state than male participants (P=0.004). Furthermore, higher educational degrees had less stress than others (P< 0.001).

Figure 5:Subscales analysis.

| Item | Never | Occasionally | Frequently | Very frequently | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performing procedures that patients experience as painful | F | 22 | 48 | 21 | 18 |

| % | 20.2 | 44 | 19.3 | 16.5 | |

| Feeling helpless in the case of a patient who fails to improve | F | 15 | 58 | 14 | 22 |

| % | 13.8 | 53.2 | 12.8 | 20.2 | |

| Listening or talking to a patient about his/her approaching death | F | 52 | 38 | 7 | 12 |

| % | 47.7 | 34.9 | 6.4 | 11 | |

| The death of a patient | F | 30 | 41 | 18 | 20 |

| % | 27.5 | 37.6 | 16.5 | 18.3 | |

| The death of a patient with whom you developed a close relationship | F | 29 | 42 | 17 | 21 |

| % | 26.6 | 38.5 | 15.6 | 19.3 | |

| Watching a patient suffer | F | 14 | 36 | 36 | 23 |

| % | 12.8 | 33 | 33 | 21.1 | |

| Criticism by a physician | F | 44 | 49 | 6 | 10 |

| % | 40.4 | 45 | 5.5 | 9.2 | |

| Conflict with a physician | F | 51 | 43 | 6 | 9 |

| % | 46.8 | 39.4 | 5.5 | 8.3 | |

| Disagreement concerning the treatment of a patient | F | 53 | 62 | 7 | 5 |

| % | 32.1 | 56.9 | 6.4 | 4.6 | |

| Inadequate information from a physician regarding the medical condition of a patient | F | 25 | 60 | 20 | 4 |

| % | 22.9 | 55 | 18.3 | 3.7 | |

| Deciding for a patient when the physician is unavailable | F | 25 | 63 | 14 | 7 |

| % | 22.9 | 57.8 | 12.8 | 6.4 | |

| A physician ordering what appears to be inappropriate for the patient | F | 43 | 47 | 17 | 2 |

| % | 39.4 | 43.1 | 15.9 | 1.8 | |

| Fear of making a mistake in treating a patient | F | 31 | 49 | 20 | 9 |

| % | 28.4 | 45 | 18.3 | 8.3 | |

| Feeling inadequately prepared to help with the emotional needs of a patient’s family | F | 30 | 59 | 15 | 5 |

| % | 27.5 | 54.1 | 13.8 | 4.6 | |

| Being asked a question by a patient for which I do not have a satisfactory answer | F | 28 | 60 | 13 | 8 |

| % | 25.7 | 55 | 11.9 | 7.3 | |

| Feeling inadequately prepared to help with the emotional needs of a patient | F | 27 | 61 | 16 | 5 |

| % | 24.8 | 56 | 14.7 | 4.6 | |

| Lack of an opportunity to talk openly with other unit personnel about problems in the unit | F | 40 | 51 | 13 | 5 |

| % | 36.7 | 46.8 | 11.9 | 4.6 | |

| Lack of an opportunity to share experiences and feelings with other personnel on the unit | F | 30 | 61 | 14 | 4 |

| % | 27.5 | 56 | 12.8 | 3.7 | |

| Lack of an opportunity to express to other personnel on the unit my negative feelings toward patients | F | 36 | 50 | 16 | 7 |

| % | 33 | 45.9 | 14.7 | 6.4 | |

| Conflict with a supervisor | F | 44 | 49 | 11 | 5 |

| % | 40.4 | 45 | 10.1 | 4.6 | |

| Floating to other units that are short-staffed | F | 22 | 60 | 18 | 9 |

| % | 20.2 | 55 | 16.5 | 8.3 | |

| Difficulty in working with a particular nurse outside the unit | F | 36 | 52 | 11 | 10 |

| % | 33 | 47.7 | 10.1 | 9.2 | |

| Difficulty in working with a particular nurse outside the unit | F | 37 | 53 | 14 | 5 |

| % | 33.9 | 48.6 | 12.8 | 4.6 | |

| Criticism by a supervisor | F | 45 | 51 | 6 | 7 |

| % | 41.3 | 46.8 | 5.5 | 6.4 | |

| Breakdown of computer | F | 28 | 61 | 10 | 10 |

| % | 25.7 | 56 | 9.2 | 9.2 | |

| Too many non-nursing tasks required such as clerical work | F | 18 | 56 | 25 | 10 |

| % | 16.5 | 51.4 | 22.9 | 9.2 | |

| Not enough time to provide emotional support to a patient | F | 23 | 65 | 16 | 5 |

| % | 21.1 | 59.6 | 14.7 | 4.6 | |

| Not enough time to complete all of my nursing tasks | F | 24 | 63 | 17 | 5 |

| % | 22 | 57.8 | 15.6 | 4.6 | |

| Not enough staff to adequately cover the unit | F | 14 | 48 | 27 | 20 |

| % | 12.8 | 44 | 24.8 | 18.3 | |

| Physician not being present when the patient dies | F | 55 | 36 | 13 | 5 |

| % | 50.5 | 33 | 11.9 | 4.6 | |

| A physician not being present in the medical emergency | F | 44 | 51 | 6 | 8 |

| % | 40.4 | 46.8 | 5.5 | 7.3 | |

| Not knowing what a patient or patient’s family ought to be told about the patient’s condition and its treatment | F | 39 | 49 | 17 | 4 |

| % | 35.8 | 45 | 15.6 | 3.7 | |

| Uncertainty regarding the operation and functioning of specialized equipment | F | 34 | 62 | 8 | 5 |

| % | 31.2 | 56.9 | 73 | 4.6 | |

Table 4: Participants’ responses to nursing stress scale items.

Discussion

Patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) who require renal replacement treatment are cared for by hemodialysis nurses. Hemodialysis is a life-sustaining procedure that continues until the patient obtains a kidney transplant or dies [16]. Patients in Australia and New Zealand typically get dialysis three times per week for four to five hours each time [17] in a variety of locations (hospitals, free-standing units, and homes; more comprehensively described in Agar et al., 2007). A hemodialysis treatment takes around 6 hours to prepare, deliver, and terminate. As a result, hemodialysis nurses routinely care for the same patient up to three times per week for a lengthy period, often years or even decades, resulting in unique nurse-patient interactions [18–20].

The hemodialysis work environment is highly technical [21], with nurses required to learn complicated hemodialysis technology to offer patients safe, efficient, and effective treatment. While patients are on dialysis, hemodialysis nurses must perform a variety of difficult responsibilities such as advocate, carer, educator, mentor, and technician [22]. The intricacies of these nurses' roles, along with organizational issues in the workplace, have resulted in significant instances of burnout among hemodialysis nurses. For example, 1 in 3 people in the United States [23] experienced burnout, as did 52% of people in Australia and New Zealand [24]. Among small Turkish research, Kavurmaci, et al. [25] discovered medium to high levels of emotional burnout in hemodialysis nurses. High levels of nurse burnout are associated with poor patient outcomes, increased sick absence, diminished organizational engagement, and an increase in nurses quitting their workplace and even the nursing profession [26,27]. Nurses report better levels of job satisfaction [28], organizational dedication, staff retention [29], and improved patient outcomes [30,31] when the work environment is evaluated positively.

Previous research has shown that empowered and supportive work cultures increase job satisfaction, reduce workplace stress, and reduce the prevalence of burnout in nurses [32–35]. The physical-socialpsychological features of the work setting are referred to as the work environment [36]. A professional work environment promotes nurses to have control over patient care delivery and the setting in which it is provided [35]. Aiken et al. [32] discovered that 25-33 percent of hospitals have bad work conditions in a major global survey comprising over 1400 hospitals from nine countries.

Kanter's Structural Empowerment Theory guided this study, which investigates the power and structural elements in the workplace and their impact on job satisfaction, stress, and burnout [33]. Power and structural issues are recognized to have an impact on the workplace [38]. According to Kanter, et al. [37,38], power can emerge through both formal and informal channels, and it influences access to empowering work structures. Formal authority is generated from the employee's position in the organization and the job attributes. Informal power exists and is more nuanced than formal power; it emerges from interactions with colleagues and social alliances formed both inside and outside of the organization [39]. Access to information (the ability to participate in organizational decisions, policies, and goals and pass the information on to other colleagues); support (receiving feedback and guidance from supervisors, peers, and subordinates to enable employees to take action in response to difficult situations); resources (access to money, materials, supplies, and equipment required to achieve organizational goals); and opportunities O'Brien [40] discovered that hemodialysis nurses reported increased levels of burnout when structural elements were missing or decreased. According to Kanter, et al. [37,38], access to these elements has a stronger influence on work attitudes and actions than personality attributes. A previous study has revealed that working in hemodialysis is stressful [41] and demanding [42]. The nursing profession has been impacted by job losses, salary cutbacks, poorer working conditions, the replacement of nurses with unregulated, less educated healthcare assistants, increasing workloads, and increased stress as health budgets have tightened [43]. These environmental elements influence a nurse's degree of job satisfaction [44].

"How employees truly feel about themselves as workers, their work, their bosses, their work environment, and their general work-life" is defined as job satisfaction [44]. Because of the interaction of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extra-personal aspects that contribute to total work satisfaction, job satisfaction is diverse and complicated [45,46]. The literature emphasizes the favorable influence that work satisfaction might have on nurse retention. High levels of job satisfaction result in psychological engagement, increased organizational commitment [29], and morale [47-49]. High levels of nurse work satisfaction have also been linked to better patient outcomes and fewer adverse occurrences [50]. Lower levels of job satisfaction, on the other hand, are caused by heavy workloads (nurse-to-patient ratios), unhappiness with remuneration, poor communication with supervisors, and a lack of clinical autonomy [51]. Low job satisfaction has been linked to higher patient morbidity and mortality [30], nurse burnout [26], and increased nurse turnover, which has resulted in nursing workforce shortages [52,53].

The work environment and nurses' demographic characteristics have previously been recognized as factors influencing hemodialysis nurses' job satisfaction [14,54]. The kind of hemodialysis setting influences job happiness, with nurses working in in-center acute units reporting lower job satisfaction than those working in a home hemodialysis unit, where the practitioner has more autonomy and patients are more self-sufficient [14]. Older nurses and those who have worked in the hemodialysis setting for a longer period are also known to have greater levels of job satisfaction [14,55], whilst those with less than three years' experience had the lowest levels of job satisfaction [14]. Other characteristics that contribute to higher levels of work satisfaction in hemodialysis nurses include having time to satisfy patients' psychological and physical requirements, as well as providing quality patient care [27,56].

Job stress, according to Lazarus , et al. [57], is "a specific interaction between the individual and the environment that the person appraises as exhausting or beyond his or her resources and harming his or her well-being p.19." Higher levels of stress are associated with decreased work satisfaction [33], worse patient outcomes [30], increased burnout [58], and higher nursing staff turnover [52]. Burnout is characterized by diminished personal accomplishment, depersonalization, and emotional weariness when stress becomes persistent (or chronic) [59]. Higher workloads [60,61], poor interpersonal relationships with colleagues [19,40,62], ineffective communication with management [62,63], intense patient-nurse relationship [64], violence and aggression from patients, and discrimination directed at nurses from patients have all been linked to job stress and burnout in hemodialysis nurses.

Conclusion

A cross-sectional descriptive, analytical design was employed to investigate hemodialysis nurses' current levels and experiences of job satisfaction, stress, and burnout. Overall, nurses were pleased with their work environment and the ability to care for patients with complicated healthcare requirements, although there were stresses that contributed to higher emotional strain. The intimate interaction between the nurse and the patients, as well as the impact of recurring sorrow, was the hemodialysis stresses.

This research gives essential insight into the nature and complexity of working as a hemodialysis nurse, allowing nurses, nurse managers, and organizations to better appreciate the benefits and stressors that these nurses encounter. Nurse Managers' stress management leadership is critical in building and maintaining a work climate conducive to job satisfaction and greater staff retention.

References

- Ma L, Zhao S. Risk factors for mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2017; 238:151–158.

- Kallenbach JZ. Review of hemodialysis for nurses and dialysis personnel-e-book. Elsevier Health Sciences 2020.

- Jennifer Dillon MPA. Registered nurse staffing, workload, and nursing care left undone, and their relationships to patient safety in hemodialysis units. Nephrol Nurs J 2020; 47:133–142.

- Chen TK, Knicely DH, Grams ME. Chronic kidney disease diagnosis and management: A review. JAMA 2019; 322:1294–1304.

- Mousa D, Alharbi A, Helal I, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of chronic kidney disease among relatives of hemodialysis patients in Saudi Arabia. Kidney Int Reports 2021; 6:817–820.

- Manandhar DN, Chhetri PK, Poudel P, et al. Knowledge and practice of hemodialysis amongst dialysis nurses. J Nepal Med Assoc 2017; 56:346–351.

- Barrios S, Catoni MI, Arechabala MC, et al. Nurses’ workload in hemodialysis units. Rev Med Chil 2017; 145:888–895.

- Shahdadi H, Rahnama M. Experience of nurses in hemodialysis care: A phenomenological study. J Clin Med 2018; 7.

- Nobahar M, Tamadon MR. Barriers to and facilitators of care for hemodialysis patients; a qualitative study. J Renal Inj Prev 2016; 5:39.

- Montoya V. Mental health and health-related quality of life among nephrology nurses: A survey-based cross-sectional study. Nephrol Nurs J 2021; 48.

- https://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/index.html%0Ahttps://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/esp/es_index.html%0Ahttps://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/esp/es_index.html%0Ahttps://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/index.html%0Ahttps://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/index.html%0Ahttps://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/esp/es_i

- https://members.nursingquality.org/MicroStrategy/asp/images/custom/pdf/NDNQI%20RN%20Survey%20with%20Pratice%20Environment%20Scale.pdf

- Norman RM, Iversen HH, Sjetne IS. Development, adaptation and psychometric assessment of the extended brisbane practice environment measure for nursing homes (B-PEM-NH) for use in the Norwegian setting. Geriatr Nurs 2019; 40:302–313.

- Every N. The Maslach burnout inventory overall score for occupational exhaustion (EE) Overall score for depersonalisation/loss of empathy (DP). Burn Out Scale 19–20.

- Porcel-Gálvez AM, Barrientos-Trigo S, Bermúdez-GarcÃa S, et al. The nursing stress scale-Spanish version: An update to its psychometric properties and validation of a short-form version in acute care hospital settings. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17.

- Agar JWM, MacGregor MS, Blagg CR. Chronic maintenance hemodialysis: Making sense of terminology. Hemodial Int 2007; 11:252–262.

- Polkinghorne K, Gulyani A, McDonald SP, et al. ANZDATA Registry Report 2010: Haemodialysis. In Edn. Adelaide, South Australia: Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry 2012.

- Bonner A. Understanding the role of knowledge in the practice of expert nephrology nurses in Australia. Nurs Health Sci 2007; 9:161–167.

- Brown S, Bain P, Broderick P, et al. Emotional effort and perceived support in renal nursing: A comparative interview study. J Ren Care 2013; 1–10.

- Polaschek N. Negotiated care: A model for nursing work in the renal setting. J Adv Nurs 2003; 42:355–363.

- Bennett PN. Technological intimacy in haemodialysis nursing. Nurs Inq 2011; 18:247–252.

- Tranter SA, Donoghue J, Baker J. Nursing the machine: An ethnography of a hospital haemodialysis unit. J Nephrol Renal Transplant 2009; 2:28–41.

- Flynn L, Thomas-Hawkins C, Clarke SP. Organizational traits, care processes, and burnout among chronic hemodialysis nurses. West J Nurs Res 2009; 31:569–582.

- Hayes B, Douglas C, Bonner A. Work environment, job satisfaction, stress and burnout in haemodialysis nurses. J Nurs Manag 2013; 23:588–598.

- Kavurmaci M, Cantekin I, Curcani M. Burnout levels of hemodialysis nurses. Ren Fail 2014; 36:1038–1042.

- Van Bogaert P, Clarke S, Willems R, et al. Nurse practice environment, workload, burnout, job outcomes, and quality of care in psychiatric hospitals: A structural equation model approach. J Adv Nurs 2013; 69:1515–1524.

- Heinen MM, van Achterberg T, Schwendimann R, et al. Nurses' intention to leave their profession: A cross sectional observational study in 10 European countries. Int J Nurs Stud 2013; 50:174–184.

- Cicolini G, Comparcini D, Simonetti V. Workplace empowerment and nurses' job satisfaction: A systematic literature review. J Nurs Manag 2013; 22:855–871.

- De Gieter S, Hofmans J, Pepermans R. Revisiting the impact of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on nurse turnover intentions: An individual differences analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2011; 48:1562–1569.

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, et al. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm 2008; 38:223–229.

- Kirwan M, Matthews A, Scott PA. The impact of the work environment of nurses on patient safety outcomes: A multi-level modelling approach. Int J Nurs Stud 2013; 50:253–263.

- Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Clarke S, et al. Importance of work environments on hospital outcomes in nine countries. International J Qual Health Care 2011; 23:357–364.

- Toh SG, Ang E, Devi MK. Systematic review on the relationship between the nursing shortage and job satisfaction, stress and burnout levels among nurses in oncology/haematology settings. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2012; 10:126–141.

- Wang X, Kunaviktikul W, Wichaikhum OA. Work empowerment and burnout among registered nurses in two tertiary general hospitals. J Clin Nurs 2013; 22:2896–2903.

- Yang J, Lui Y, Huang C, et al. Impact of empowerment on professional practice environments and organizational commitment among nurses: A structural equation approach. Int J Nurs Pract 2013; 19:44–55.

- Chan AOM, Huak CY. Influence of work environment on emotional health in a health setting. Occup Med 2004; 54:207–212.

- Kanter RM. Men and women of the corporation. Part 2. New York: Basic Books; 1993.

- Kanter RM. Men and women of the corporation. New York: Basic Books; 1977.

- Kanter RM. Power failure in management circuits. Harv Bus Rev 1979; 57:65–75.

- O'Brien JL. Relationships among structural empowerment, psychological empowerment, and burnout in registered staff nurses working in outpatient dialysis centers. Nephrol Nurs J 2011; 38:475–481.

- Ashker VE, Penprase B, Salman A. Work-related emotional stressors and coping strategies that affect the well-being of nurses working in hemodialysis units. Nephrol Nurs J 2012; 39:231–236.

- Ross J, Jones J, Callaghan P, et al. A survey of stress, job satisfaction and burnout among haemodialysis staff. J Ren Care 2009; 35:127–133.

- Wray J. The impact of the financial crisis on nurses and nursing. J Adv Nurs 2013; 69:497–499.

- Castaneda GA, Scanlan JM. Job satisfaction in nursing: A concept analysis. Nurs Forum 2014; 49:130–138.

- Hayes B, Bonner A, Pryor J. Factors contributing to nurse satisfaction in the acute hospital setting: Review of recent literature. J Nurs Manag 2010; 18:804–814.

- Lu H, While AE, Barriball L. Job satisfaction among nurses: A literature review. Int J Nurs Stud 2005; 42:211–227.

- Carter MR, Tourangeau AE. Staying in nursing: What factors determine whether nurses intend to remain employed. J Adv Nurs 2012; 68:1589–1600.

- Ellenbecker CH, Cushman M. Home healthcare nurse retention and patient outcome model: Discussion and model development. J Adv Nurs 2012; 68:1881–1893.

- Currie EJ, Carr Hill RA. What are the reasons for high turnover in nursing? A discussion of presumed causal factors and remedies. Int J Nurs Stud 2012; 49:1180–1189.

- Aiken LH, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, et al. Effects of nursing staffing and nurse education on patient deaths in hospitals with different nurse work environments. Med Care 2011; 49:1047–1053.

- Kaddourah BT, Khalidi A, Abu-Shaheen A, et al. Factors impacting job satisfaction among nurses from a tertiary care centre. J Clin Nurs 2013; 22:3153–3159.

- Chan Z, Tam WS, Lung MKY, et al. A systematic literature review of nurse shortage and intention to leave. J Nurs Manag 2013; 21:605–613.

- Cowin LS, Johnson M, Craven RG, et al. Causal modeling of self-concept, job satisfaction, and retention of nurses. J Nurs Adm 2008; 45:1449–1459.

- Hayes B, Douglas C, Bonner A. Predicting emotional exhaustion among haemodiaysis nurses: A structural equation model using Kanter's structural empowerment theory. J Adv Nurs 2014; 70:2897–2909.

- Arikan F, Köksal CD, Gökçe Ã?. Work-related stress, burnout, and job satisfaction of dialysis nurses in association with perceived relations with professional contacts. Dial Transplant 2007; 36:182–191.

- Perumal S, Sehgal AR. Job satisfaction and patient care practices of hemodialysis nurses and technicians. Nephrol Nurs J 2003; 30:523–528.

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York Springer 1984.

- Garcia-Izquierdo M, Rios-Risquez MI. The relationship between psychosocial job stress and burnout in emergency departments: An exploratory study. Nurs Outlook 2012; 60:322–329.

- Maslach C, Leiter MP. The truth about burnout: How organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass 1997.

- Dermondy K, Bennett PN. Nurse stress in hospital and satellite haemodialysis units. J Ren Care 2008; 34:28–32.

- Thomas-Hawkins C, Flynn L, Clarke SP. Relationships between registered nurse staffing, processes of nursing care, and nurse-reported patient outcomes in chronic hemodialysis units. Nephrol Nurs J 2008; 35:123–145.

- Murphy F. Stress among nephrology nurses in Northern Ireland. Nephrol Nurs J 2004; 31:423–431.

- Brokalaki H, Matziou J, Thanou J, et al. Job-related stress among nursing personnel in Greek dialysis units. EDTNA/ERCA J 2001; 27:181–186.

- Dolan G, Strodl E, Hamernik E. Why renal nurses cope so well with their workplace stressors. J Ren Care 2012; 38:222–232.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Appendices

Appendix 1: Study timeframe and budget.

| Timeframe | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb-22 | Mar-22 | Mar-22 | Mar-22 | Apr-22 | Apr-22 | May-22 | May-22 | Jun-22 | |

| Preparing the research proposal | |||||||||

| Preparing the research instruments | |||||||||

| Obtaining the ethical approval | |||||||||

| Data collection | |||||||||

| Data management and analysis | |||||||||

| Writing the research paper | |||||||||

Appendix 2: Study budget.

| Study Budget | |

|---|---|

| Data Collection Fees | 1000 SR |

| Data Analysis Fees | 1200 SR |

Appendix 3: Questionnaire.

| Demographic and work characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | Nationality | Saudi |

| Female | Non-Saudi | ||

| Age | 20-30 | Primary role | Staff nurse |

| 31-40 | Charge nurse | ||

| 41-50 | Advanced practice Nurse | ||

| 51-60 | Coordinator of clinical program | ||

| 61 and more | Nurse manager | ||

| Job situation | Full time [>=36 hours per week] | Research role | |

| Part time [<36 hours per week] | Another role | ||

| Volunteer | Highest nursing license | Not licensed | |

| Another situation | Diploma | ||

| Duration of work at the current role | < 3 months | Bachelor degree | |

| 3-6 months | Master's Degree | ||

| 6 months - 2 years | PHD | ||

| 2-5 years | Professor Assistant | ||

| 5-10 years | Others | ||

| >10 years | |||

Appendix 4: The National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators Index 2018 (NDNQI-Index).

| The National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators Index 2018 (NDNQI-Index) 1- Index of Work Satisfaction |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice Environment Scale | ||||||

| Practice Environment Scale For each item, please indicate the extent to which you agree that the item is present in your current job |

||||||

| Nurse participation in hospital affairs | ||||||

| Strongly agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |||

| Career development/clinical ladder opportunity | ||||||

| Opportunity for staff nurses to participate in policy decisions | ||||||

| A chief nursing officer which is highly visible and accessible to staff | ||||||

| A chief nursing officer equal in power and authority to other top-level hospital executives | ||||||

| Opportunities for advancement | ||||||

| Administration that listens and responds to employee concerns | ||||||

| Staff nurses are involved in the internal governance of the hospital (e.g., practice and policy committees) | ||||||

| Staff nurses have the opportunity to serve on hospital and nursing committees | ||||||

| Nursing administrators consult with staff on daily problems and procedures | ||||||

| Nursing foundations for quality of care | ||||||

| Active staff development or continuing education programs for nurses | ||||||

| High standards of nursing care are expected by the administration | ||||||

| A clear philosophy of nursing that pervades the patient care environment | ||||||

| Working with nurses who are clinically competent | ||||||

| An active quality assurance program | ||||||

| A preceptor program for newly hired RNs | ||||||

| Nursing care is based on a nursing, rather than a medical, model | ||||||

| Written, up-to-date nursing care plans for all patients | ||||||

| Patient care assignments that foster continuity of care, i.e., the same nurse cares for the patient from one day to the next | ||||||

| Use of nursing diagnoses | ||||||

| Nurse manager ability, leadership, and support of nurses | ||||||

| A supervisory staff that is supportive of the nurses | ||||||

| Supervisors use mistakes as learning opportunities, not criticism | ||||||

| A nurse manager who is a good manager and leader | ||||||

| Praise and recognition for a job well done | ||||||

| A nurse manager who backs up the nursing staff in decision-making, even if the conflict is with a physician | ||||||

| Staffing and resource adequacy | ||||||

| Adequate support services allow me to spend time with my patients | ||||||

| Enough time and opportunity to discuss patient care problems with other nurses | ||||||

| Enough registered nurses to provide quality patient care | ||||||

| Enough staff to get the work done | ||||||

| Collegial nurse physician relations | ||||||

| Physicians and nurses have good working relationships | ||||||

| A lot of team work between nurses and physicians | ||||||

| Collaboration (joint practice) between nurses and physicians | ||||||

| Nurse-Nurse Interaction Scale | ||||||

| Based on your experience, please indicate your agreement or disagreement with the following statements about your unit and the RNs with whom you work | ||||||

| Strongly agree | Agree | Tend to agree | Tend to disagree | disagree | Strongly disagree | |

| RNs I work with count on each other to pitch in and help when things get busy | ||||||

| There is a good deal of teamwork among RNs I work with | ||||||

| RNs I work with support each other | ||||||

| Job Enjoyment Scale | ||||||

| Based on your experience, please indicate your agreement or disagreement with the following statements about your unit and the RNs with whom you work | ||||||

| As RNs, we are fairly well satisfied with our jobs on our unit | ||||||

| RNs on our unit would not consider taking another job | ||||||

| I have to force myself to come to work much of the time | ||||||

| RNs on our unit are enthusiastic about our work almost every day | ||||||

| RNs on our unit like our jobs better than the average RN does | ||||||

| I feel that each day on my job will never end | ||||||

| We find real enjoyment in our work on our unit | ||||||

| Unit RN Job Plans for Next Year/next 3 years | ||||||

| What are your job plans for the next year? Next 3 years? | Stay in my current position | |||||

| Stay in direct patient care but in another unit in this hospital | ||||||

| Stay in direct patient care but outside this hospital | ||||||

| Leave direct patient care but stay in the nursing profession | ||||||

| Leave the nursing profession for another career | ||||||

| Retire | ||||||

| Please select the main reason you plan to leave your current position (if applicable) | Dissatisfaction | |||||

| Change in nursing career | ||||||

| Home/Personal life | ||||||

| Unit Perceived Quality of Care | ||||||

| In general, how would you describe the quality of nursing care delivered to patients on your unit? | Excellent | |||||

| Good | ||||||

| Fair | ||||||

| Poor | ||||||

| Description of Unit Last Shift | ||||||

| Think about the last shift that you worked. Please indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree that the following situation occurred. 1. My patient care assignment was appropriate, considering both the number of patients and the care they required |

Tend to agree | |||||

| Tend to disagree | ||||||

| Disagree | ||||||

| Strongly Disagree | ||||||

| Think about the last shift you worked. 2. At any one time what was the maximum number of patients assigned to you? | 1 | |||||

| 5-Feb | ||||||

| 10-Jun | ||||||

| More than 10 | ||||||

| 3. Over your entire shift what was the total number of patients assigned to you? | 1 | |||||

| 5-Feb | ||||||

| 10-Jun | ||||||

| More than 10 | ||||||

| 4. How many hours did you work? | Less than 6 | |||||

| 12-Jun | ||||||

| More than 12 | ||||||

Appendix 5: Brisbane Practice Environment Measure (B-PEM).

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Frequently | Always | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I feel supported by my line manager | |||||

| 2. Performance and appraisal are completed in this area | |||||

| 3. In this area staff get away with bad behavior | |||||

| 4. I feel respected in the way people speak to me | |||||

| 5. I am able to change my roster if necessary | |||||

| 6. There is time for staff development | |||||

| 7. It is difficult to influence change in this area | |||||

| 8. There is a great team spirit in my work area | |||||

| 9. My line manager is responsive to emergent leave | |||||

| requirements | |||||

| 10. I am treated as an individual | |||||

| 11. There is equity in staff development opportunities | |||||

| 12. My skills are acknowledged | |||||

| 13. I participate in roster development | |||||

| 14. My line manager is approachable | |||||

| 15. Off line time is offered for professional development | |||||

| 16. I am thrown in at the deep end | |||||

| 17. The workload is overwhelming in this area | |||||

| 18. I have access to the information I need to do my job | |||||

| 19. I feel intimidated when working in this area | |||||

| 20. There is equity in rostering in this area | |||||

| 21. I am acknowledged when I put in extra effort | |||||

| 22. The skill mix is about right in this area | |||||

| 23. In this area, clinical resources are adequate | |||||

| 24. I am asked to operate outside my scope of practice | |||||

| 25. There is a high level of clinical expertise I can access | |||||

| 26. I feel just like a number | |||||

| 27. There is support for professional development in my area | |||||

| 28. Continuity of care is considered in this area | |||||

| 29. I enjoy coming to work | |||||

| 30. Our roster complies with roster regulations | |||||

| 31. My line manager is ready to help out in the clinical area | |||||

| 32. Staff workloads are equal | |||||

| 33. Opportunities for advancement are available in this organisation |

Appendix 6: The maslach burnout inventory.

0=Never1=At least a few times a year

2=At least once a month

3=Several times a month

4=Once a week

5=Several times a week

6=Every day

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 – I feel emotionally exhausted because of my work | |||||||

| 02 – I feel worn out at the end of a working day | |||||||

| 03 – I feel tired as soon as I get up in the morning and see a new working day stretched out | |||||||

| in front of me | |||||||

| 04 – I can easily understand the actions of my colleagues/supervisors | |||||||

| 05 – I get the feeling that I treat some clients/colleagues impersonally, as if they were objects | |||||||

| 06 – Working with people the whole day is stressful for me | |||||||

| 07 – I deal with other people’s problems successfully | |||||||

| 08 – I feel burned out because of my work | |||||||

| 09 – I feel that I influence other people positively through my work | |||||||

| 10 –I have become more callous to people since I have started doing this job | |||||||

| 11 – I’m afraid that my work makes me emotionally harder | |||||||

| 12 – I feel full of energy | |||||||

| 13 – I feel frustrated by my work | |||||||

| 14 – I get the feeling that I work too hard | |||||||

| 15 – I’m not really interested in what is going on with many of my colleagues | |||||||

| 16 – Being in direct contact with people at work is too stressful | |||||||

| 17 – I find it easy to build a relaxed atmosphere in my working environment | |||||||

| 18 – I feel stimulated when I been working closely with my colleagues | |||||||

| 19 – I have achieved many rewarding objectives in my work | |||||||

| 20 – I feel as if I’m at my wits‘ end | |||||||

| 21 – In my work I am very relaxed when dealing with emotional problems | |||||||

| 22 – I have the feeling that my colleagues blame me for some of their problems |

Appendix 7: Nursing Stress Scale (NSS).

| Never | Occasionally | Frequently | Very frequently | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subscale (1): Death and Dying | ||||

| 3. Performing procedures that patients experience as painful | ||||

| 4. Feeling helpless in the case of a patient who fails to improve | ||||

| 6. Listening or talking to a patient about his/her approaching death | ||||

| 8. The death of a patient | ||||

| 12. The death of a patient with whom you developed a close relationship | ||||

| 21. Watching a patient suffer | ||||

| Subscale (2): Conflict With Physicians | ||||

| 2. Criticism by a physician | ||||

| 9. Conflict with a physician | ||||

| 14. Disagreement concerning the treatment of a patient | ||||

| 17. Inadequate information from a physician regarding the medical condition of a patient | ||||

| 19. Making a decision concerning a patient when the physician is unavailable | ||||

| 26. A physician ordering what appears to be inappropriate treatment for a patient | ||||

| Subscale (3): Inadequate Preparation | ||||

| 10. Fear of making a mistake in treating a patient | ||||

| 15. Feeling inadequately prepared to help with the emotional needs of a patient’s family | ||||

| 18. Being asked a question by a patient for which I do not have a satisfactory answer | ||||

| 23. Feeling inadequately prepared to help with the emotional needs of a patient | ||||

| Subscale (4): Lack of Support | ||||

| 7. Lack of an opportunity to talk openly with other unit personnel about problems on the unit | ||||

| 11. Lack of an opportunity to share experiences and feelings with other personnel on the unit | ||||

| 16. Lack of an opportunity to express to other personnel on the unit my negative feelings toward patients | ||||

| Subscale (5): Conflict With Other Nurses | ||||

| 5. Conflict with a supervisor | ||||

| 20. Floating to other units that are shortstaffed | ||||

| 22. Difficulty in working with a particular nurse (or nurses) outside the unit | ||||

| 24. Criticism by a supervisor | ||||

| 25. Unpredictable staffing and scheduling | ||||

| 29. Difficulty in working with a particular nurse (or nurses) on the unit | ||||

| Subscale (6): Work Load | ||||

| 1. Breakdown of computer | ||||

| 27. Too many non-nursing tasks required, such as clerical work | ||||

| 28. Not enough time to provide emotional support to a patient | ||||

| 30. Not enough time to complete all of my nursing tasks | ||||

| 34. Not enough staff to adequately cover the unit. | ||||

| Subscale (7): Uncertainty Concerning Treatment | ||||

| 13. Physician not being present when a patient dies | ||||

| 31. A physician not being present in a medical emergency | ||||

| 32. Not knowing what a patient or a patient’s family ought to be told about the patient’s condition and its treatment | ||||

| 33. Uncertainty regarding the operation and functioning of specialized equipment | ||||

Author Info

Shaaban Nasser Al Shawan1*, Bayapa Reddy Narapureddy2, Fayez Mari Alamri3 and Khalid Nasser Al Shawan4

1Nursing specialist, Rejal Almaa general Hospital, Ministry of Health, KSA2College of Applied Medical Sciences, Ministry of Education, Khamis Mushait, KSA

3Nursing Technician, Asser Health Affairs, Ministry of Health, KSA

4Assistant Specialist-Health Administration, Mohayl General Hospital, Ministry of Health, KSA

Received: 14-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. jrmds-22-79667; , Pre QC No. jrmds-22-79667(PQ); Editor assigned: 17-Oct-2022, Pre QC No. jrmds-22-79667(PQ); Reviewed: 02-Nov-2022, QC No. jrmds-22-79667(Q); Revised: 01-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. jrmds-22-79667(R; Published: 08-Nov-2022