Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 11

Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes and Risk of Progression to Type 2 Diabetes among pregnant Women in Taif community in Saudi Arabia

Afnan Mesfer Alotaibi1, Asma Abdullah Al-Dhasi2*, Rasan Faisal Almnjwami2, Ghadah Aedh Alzaidi2 and Arwa Aloush Almutairi2

*Correspondence: Asma Abdullah Al-Dhasi, Medical Intern, Taif, Makkah, KSA, Email:

Abstract

Background: Gestational diabetes is considered as a global public health problem with a higher lifetime to develop type 2 Diabetes in the following years. In this study aimed to assess the Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes and its Risk for Progression to Type 2 Diabetes among pregnant women in Taif Saudi Arabia. Objective:: This cross-sectional study was to assess the Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes in relation to demographic data among pregnant women in Taif community in Saudi Arabia. Our study was also designed to assess the Risk of Progression to Type 2 Diabetes among pregnant women in Taif community in Saudi Arabia. Methodology: A Cross-Sectional study was done in the Western Region of Saudi Arabia city of Taif, in September of 2021 until September of 2022. Our study population was pregnant women and women suffering from Type 2 diabetes after delivery who live in the Taif city. Sample sizes of 474 women who live in the Taif city and suffered from diabetes only during pregnancy or still have diabetes after delivery were included in the study. women who do not live in the Taif city and never become pregnant were excluded from this study. The survey was conducted using an electronic questionnaire written in Arabic and English. Results: A total sample size of 474 women were enrolled in our study, 86.40% of them had gestational diabetes. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus among women who experienced gestational diabetes before in Taif community in Saudi Arabia is 26.2%. Female risk factors to develop T2DM after surfing from gestational diabetes significant factors were aged 30-50 years (p <0.001), educational level (p 0.003), family history of Diabetes (p 0.003), history of stillbirth (p 0.015), using insulin during suffering from gestational diabetes (p <0.001), follow up GD or check blood glucose after delivery (p 0.006) using Chi-square test. Conclusion: A high prevalence of GDM was noted in our study; risk factors to develop T2DM after suffering from GDM were increased age, higher educational level, family history of diabetes, history of stillbirth, using insulin during pregnancy, and follow up GD or check blood glucose after delivery enhance early discover. The screening program during pregnancy, preferably early in the first trimester, for pre-GDM, as well as postpartum screening for hyperglycemia is highly warranted. The clinical accuracy of diagnosis and determined modifiable risk factors has been designated an area requiring further research and evaluation.

Keywords

Gestational diabetes mellitus, Prevalence, Diabetes mellitus, Type 2, Taif

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is one of the most common metabolic complications of pregnancy. It is defined as a kind of glucose intolerance that develops first time during pregnancy which full fill the diagnostic criteria done between 24 and 28 weeks of pregnancy. Different assays, such as the 75 oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), or glycosylated hemoglobin A1C, are equally efficient for screening for impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and diabetes, as per the American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines (HbA1c) [1,2]. In Saudi Arabia, GDM affects between 8% and 19% of the population [3,4]. Women with gestational diabetes have a 7.4% higher life time chance of developing postpartum overt type 2 diabetes [5]. In the following years, with point estimates ranging significantly depending on follow-up time and community factors [6].

GDM usually it is associated with many risk factors that may lead to many different complications. In general, several risk factors have been linked to the development of GDM. Obesity, advanced maternal age, physical inactivity, a history of GDM, a strong family history of diabetes, belonging to an ethnic group with a high prevalence of T2DM, polycystic ovary syndrome, and persistent glycosuria are the most common risk factors. Other risk factors for GDM include a history of delivering a large baby (birth weight >4000 g), a history of repeated abortions, a history of unexplained stillbirths, and a history of essential hypertension or pregnancy-related hypertension [7].

Previous studies showed populations with a high prevalence of GDM also have an increased Type 2DM prevalence [3,4,8]. So Interventions such as preconception care, screening and control of hyperglycemia during pregnancy have been proven to decrease the complications. Hence, it is important to estimate the burden of diabetes and its complication among pregnant women to direct health resource to improve the outcomes for these high-risk pregnancies [9,10].

Insufficient information about the prevalence of Gestational Diabetes and the risk of progression to Type 2 Diabetes among Taif pregnant women, so we study to know more information about the prevalence of Gestational Diabetes and the risk of progression to Type 2 Diabetes among pregnant women in Taif community in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of Taif University. A Cross-Sectional study was done in the Western Region of Saudi Arabia city of Taif, in September of 2021 until September of 2022.

Our study population was pregnant women and women suffering from Type 2 diabetes after delivery who live in the Taif city.

A sample size of 474 women who live in the Taif city and suffered from diabetes only during pregnancy or still have diabetes after delivery was included in the study. Women who do not live in the Taif city and never become pregnant were excluded from this study.

The questionnaire was adopted and validated by the data from a pilot study of 20 pregnant women was utilized to assess reliability and validity. The developed questionnaire's content, face, and construct validity were evaluated. An expert committee and focus group discussions were employed to assess content and face validity.

The survey was conducted using an electronic questionnaire written in Arabic and English where sociodemographic information, prevalence about gestational diabetes and progression to type 2 diabetes Miletus was addressed.

Data entry was performed using Microsoft Excel 2010 and statistical analysis was done via SPSS V23.

Results

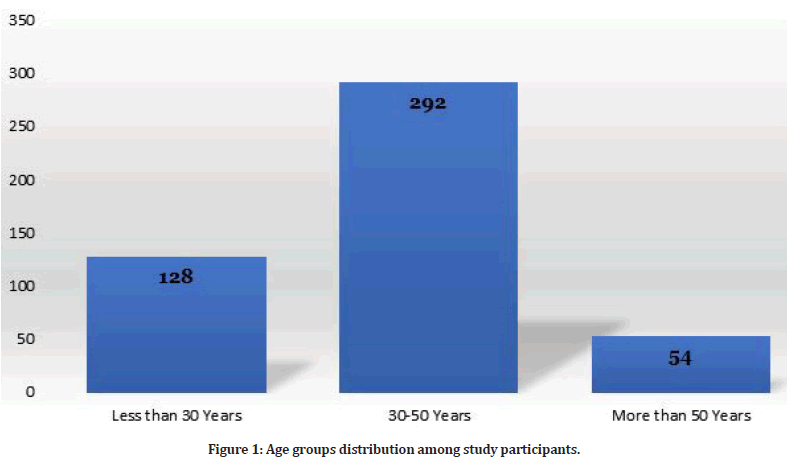

The study included 474 pregnant women. Among them, 453 women had previous pregnancy (95.6%). There are 401 women who had gestational diabetes (prevalence of GDM: 84.6%). Age distribution among study participants is clarified in Figure 1. The most frequent age group was 30-50 years (n=292, 61.6%).

Figure 1: Age groups distribution among study participants.

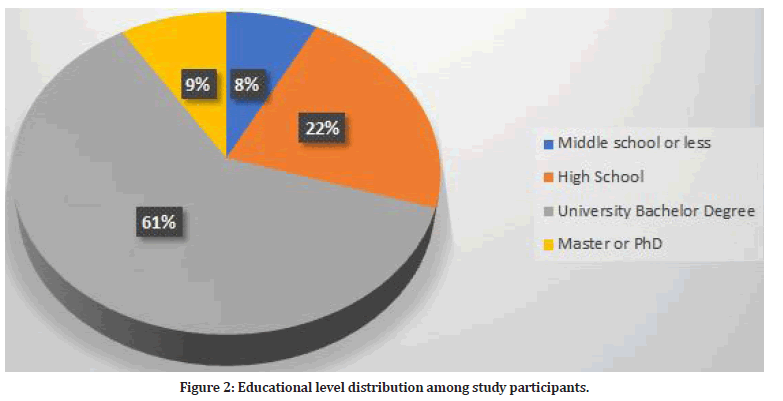

Among study participants, 434 were Saudi (91.6%) and the rest were non-Saudi (n=40, 8.4%). In addition, 341 women were residents in Taif (71.9%) and the rest (n=133, 28.1%) were residents outside Taif. The most frequent level of education among study participants was bachelor degree (n=290, 61.2%). Figure 2 shows the distribution of educational level among study participants.

Figure 2: Educational level distribution among study participants.

The median age at diagnosis of gestational diabetes was 32 years. The median weight at diagnosis was 87 kg and the median height at diagnosis was 1.55 m. This reflects high body mass index among participants at time of diagnosis (median BMI 36.2 kg/m2).

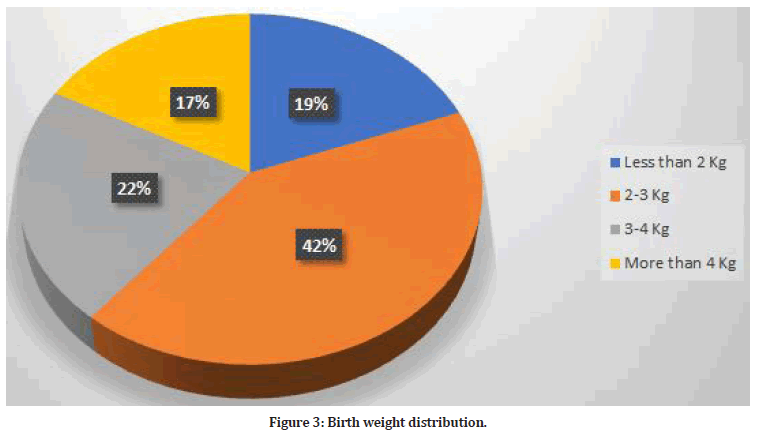

The outcome of pregnancy among women included in this study was measured by many factors. The most frequent birth weight was 2-3 kg (n=198, 41.8%). Figure 3 shows the distribution of birth weight. There were 44 babies had congenital malformation (9.3%).

Figure 3:Birth weight distribution.

Women included in this study were asked about having hypertension during their pregnancy. There were 137 women had hypertension (28.9%). Furthermore, 331 women had a family history of diabetes (69.8%).

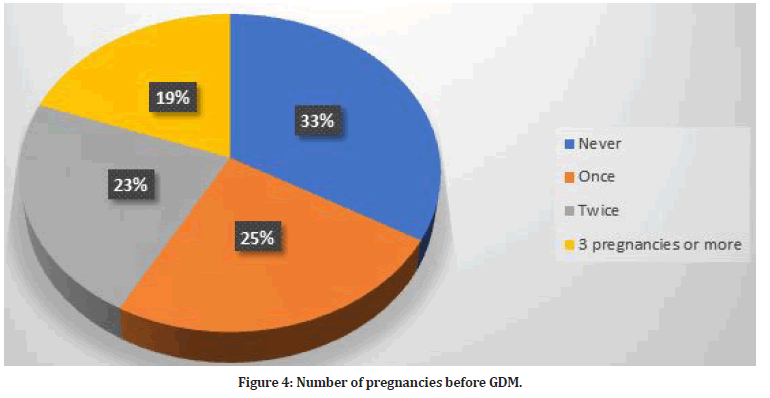

Some of study participants had a history of stillbirth (n=74, 15.6%). Also, 125 women had polycystic ovarian syndrome (26.4%). Previous abortion was prevalent among 166 (35%). Preterm labor occurred among 100 women (21.1%). The times of pregnancy before the diagnosis of gestational diabetes are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4:Number of pregnancies before GDM.

There were 172 women had used insulin during their pregnancy (36.3%). Moreover, 38 women were smokers during their pregnancy (8%). Most of women included in this study had followed their diabetes status after pregnancy (n=325, 68.6%). Finally, 124 women still had the diabetes after the delivery (26.2%).

This study highlights a prevalence of gestational diabetes of 86.4% among study participants and 26.2% progression to diabetes after delivery.

The relationship between the occurrences of diabetes after delivery among women included in this study and had gestational diabetes with sociodemographic data is presented in table. Table 1 shows female risk factors to develop T2DM after surfing from gestational diabetes significant factors were aged 30-50 years (p <0.001); educational level bachelor degree had the highest risk (p 0.003). In addition, two pregnancies are at highest risk of developing DM in after pregnancy (p 0.012). Table 2 shows female risk factors to develop T2DM after surfing from gestational diabetes significant factors were family history of Diabetes (p 0.003), history of stillbirth (p 0.015), Have used insulin during suffered from gestational diabetes (p <0.001), follow up GD or check blood glucose after delivery (p 0.003).

| Female risk factors | still have diabetes after delivery Or suffering from Type 2 diabetes after delivery (n=474) | Chi square | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||

| Age | <30 years | 114 | 14 | 12.51 | <0.001 |

| 30-50 years | 214 | 78 | |||

| >50 years | 22 | 32 | |||

| Nationality | Saudi | 322 | 112 | 0.188 | 0.784 |

| Non-Saudi | 28 | 12 | |||

| Residence city | Taif | 252 | 89 | 0.5 | 0.087 |

| Others | 98 | 35 | |||

| Educational level | Middle school or less | 21 | 15 | 12.332 | 0.003 |

| High school | 74 | 32 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 229 | 61 | |||

| Master’s degree/PhD | 26 | 16 | |||

| Smoking during pregnancy | No | 326 | 110 | 0.319 | 0.745 |

| Yes | 24 | 14 | |||

| birth before you had gestational diabetes | 0 time | 139 | 19 | 9.581 | 0.012 |

| 1 time | 89 | 28 | |||

| 2 time | 68 | 39 | |||

| >3 time | 54 | 38 | |||

Table 1: Type 2 diabetes mellitus after delivery among female surfing from gestational diabetes sociodemographic data.

| birth before you had gestational diabetes | 0 time | 139 | 19 | 9.581 | 0.012 | |

| 1 time | 89 | 28 | ||||

| 2 time | 68 | 39 | ||||

| >3 time | 54 | 38 | ||||

| Gestational data | still have diabetes after delivery Or suffering from Type 2 diabetes after delivery | Chi square | P value | |||

| No | Yes | |||||

| weight of your child | <2000 grams (<2 kg) | 74 | 17 | 5.969 | 0.475 | |

| 2000- 3000 grams | 164 | 34 | ||||

| 3000-4000 grams | 69 | 35 | ||||

| >4000 grams | 43 | 38 | ||||

| Any congenital abnormalities | No | 328 | 102 | 0.739 | 0.432 | |

| Yes | 22 | 22 | ||||

| hypertension during pregnancy | No | 274 | 63 | 2.477 | 0.237 | |

| Yes | 76 | 61 | ||||

| family history of Diabetes | No | 127 | 16 | 7.31 | 0.003 | |

| Yes | 223 | 108 | ||||

| history of stillbirth | No | 313 | 87 | 5.054 | 0.015 | |

| Yes | 37 | 37 | ||||

| polycystic ovary syndrome | No | 271 | 78 | o.715 | 0.247 | |

| Yes | 79 | 46 | ||||

| abortion | No | 243 | 65 | 1.316 | 0.078 | |

| Yes | 107 | 59 | ||||

| preterm delivery | No | 292 | 82 | 3.749 | 0.067 | |

| Yes | 58 | 42 | ||||

| Have used insulin during suffered from gestational diabetes | No | 263 | 39 | 17.212 | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 87 | 85 | ||||

| follow up GD or check blood glucose after delivery | No | 350 | 0 | 7.569 | 0.003 | |

| Yes | 0 | 124 | ||||

Table 2: Type 2 diabetes mellitus after delivery among female surfing from gestational diabetes gestational data.

Discussion

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) is diagnosed as any level of glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy [11]. The international burden of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is not well estimated, and analysis of factors influencing global prevalence estimates of GDM is lacking. Our study showed clearly that the prevalence of GDM among our participants in Taif geographical area is 84%, which is a large percentage.

Saudi Arabia is considered one of the top ten countries universally with the highest prevalence of diabetes [12], and the ratio of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in Riyadh, the capital city of Saudi Arabia, is measured to be 24.3% [13]. Comparisons of GDM burden in different countries are challenging given the great heterogeneity in screening methodology, diagnostic criteria, and underlying population characteristics. The incidence rate has increased since 2010 by two to three folds, from low rates (1 to 14%) to reach (8.9% to 53.4%) depending on the population studied and the diagnostic tests employed [1,14]. This sharp rise is primarily due to adopting the new criteria proposed by the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) for the screening and diagnosis of GDM [15].

Prevalence varies markedly across the globe as the Middle East and North Africa reported the highest prevalence of GDM with a median estimate of 12.9 % (range 8.4–24.5 %), the prevalence estimates ranged from 8.4 % in Iran to 24.5 % in the United Arab Emirates, whereas Qatar, Bahrain, and Israel had reasonable measures (i.e., 16.3, 12.9, and 8.8 %, respectively), followed by Southeast Asia, Western Pacific, America, Africa, and Caribbean (median prevalence 11.7, 11.7, 11.2, 8.9, and 7.0 %, respectively), whereas Europe had the lowest prevalence (median 5.8 %, Ireland having the lowest prevalence of 1.8 %, In contrast, Canada showed 6.5 %. Malaysia had the highest prevalence of 18.3 % in Asia, followed by India (13.6 %) [16]. The prevalence of GDM is getting higher with older moms, weight, BMI, and blood pressure.

Furthermore, having GDM in prior pregnancies, multiparity, past recurrent abortions, previous preterm births, delivering a deformed child, and having a family history of diabetes were more likely in the GDM group than in the non-GDM group [15].

The high prevalence of GDM in Saudi women is most likely due to the growing incidence of obesity, the high prevalence of type 2 diabetes, and the Saudi women's practice of conceiving at an earlier age [15]. Screening methods and diagnostic criteria, clinical standards, and medical practice varied from one nation to the next. There has always been a constant dispute among various societies about the best technique to diagnose GDM: ACOG stands for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, ADA stands for the American Diabetes Association, ADIPS stands for Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society, CDA stands for Canadian Diabetes Association, EASD stands for European Association for the Study of Diabetes, IADPSG stands for International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups, JSOG stands for Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and WHO stands for World Health Organization. Notably, diagnostic criteria for GDM have developed fast during the last few decades. [16].

The risk of conversion from GDM to T2DM postpartum is rising; however highly variable across countries and studies, which could be attributed to variability in the diagnostic criteria of GDM and/or T2DM, followup years, retention rate, and characteristics of the underlying populations. [16], the mean length of followup ranges from 5.5 months [17] to 15 years [18].

The cumulative incidence of T2DM following GDM ranges from 2.1 percent in Germany to 35.7 percent in Sweden, with the United States having an unusually high risk of acquiring T2DM after seven years of followup (RR=47.3; 95 percent CI 3.0-757.3; cumulative risk of T2DM 66.7 percent) [16]. In a big systematic review and a meta-analysis done recently involving Twentyeight studies involving 170,139 women with GDM and 34,627 reported cases of T2DM were documented. The cumulative prevalence of T2DM after GDM was 26.20 (95% CI, 23.31 to 29.10) per 1000 person-years. Asians Women, especially those with older age and higher body mass index seem to experience an increased probability of developing T2DM. The prevalence rate of T2DM was lowest when implementing IADPSG (7.16 per 1000 person-years) to diagnose GDM. The risk of developing T2DM after GDM increased in a direct positive linear fashion with the duration of follow-up. The increments per year of follow-up were estimated at 9.6‰. The calculated risks for T2DM were 19.72% at 10 years, 29.36% at 20 years, 39.00% at 30 years, 48.64% at 40 years, and 58.27% at 50 years, respectively [19]. Generally, authors believe that women with a history of GDM may be subjected to a sevenfold increased risk of T2DM in future life [20].

Our study reported that significant risk factors to develop T2DM after surfing from gestational diabetes were age (p <0.001), educational level (p 0.003), family history of Diabetes (p 0.003), history of stillbirth (p 0.015), using insulin during gestational diabetes (p <0.001), follow up GD or check blood glucose after delivery (p 0.003).

In a recent 2020 study, the risk of converting to T2DM was higher for Asian women with GDM; statistically significant factors included increased age, higher BMI, and more visceral adipose tissue compared to other ethnic races, whereas the risk was lower when the IADPSG guidelines were used to diagnose GDM [14]. Moreover, in one study by Cho and his colleagues the incidence of T2DM after GDM status depends on the number of pre-pregnancy risk factors [21]. The strengths of this cross sectional study lie in its inclusion of a good cohort of pregnant women; who have GDM and free from GDM, the universal screening and the analysis of large amounts of data on maternal characteristics and possible risk factors. A limitation of the study was that it was conducted in only one region of Saudi Arabia, and there is probability of selection bias in sampling technique, so the high prevalence of GDM in Saudi women cannot be simply generalized to the general population [22-28].

Conclusion

A high prevalence of GDM was noted in our study; risk factors to develop T2DM after suffering from GDM were increased age, higher educational level, family history of diabetes, history of stillbirth, using insulin during pregnancy, and follow up GD or check blood glucose after delivery enhance early discover. The screening program during pregnancy, preferably early in the first trimester, for pre-GDM, as well as postpartum screening for hyperglycemia is highly warranted. The clinical accuracy of diagnosis and determined modifiable risk factors has been designated an area requiring further research and evaluation.

References

- American Diabetes Association. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2004; 27:88-90.

- American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic targets: standards of medical care in diabetesâ??2018. Diabetes Care 2018; 41:55-64.

- Abdelmola AO, Mahfouz MS, Gahtani MA, et al. Gestational diabetes prevalence and risk factors among pregnant womenâ??Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia. Clin Diabetol 2017; 6:172-177.

- Wahabi HA, Esmaeil SA, Fayed A, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus: Maternal and perinatal outcomes in King Khalid University Hospital, Saudi Arabia. J Egypt Public Health Assoc 2013; 88:104-108.

- Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009; 373:1773-1779.

- Coustan DR. Recurrent GDM and the development of type 2 diabetes have similar risk factors. Endocrine 2016; 53:624-625.

- Solomon CG, Willett WC, Carey VJ, et al. A prospective study of pregravid determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus. JAMA 1997; 278:1078-1083.

- Wahabi H, Fayed A, Esmaeil S, et al. Prevalence and complications of pregestational and gestational diabetes in Saudi women: analysis from Riyadh Mother and Baby cohort study (RAHMA). BioMed Res Int 2017; 2017.

- Alfadhli EM. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Saudi Med J 2015; 36:399.

- Pérez-Ferre N, Del Valle L, Torrejón MJ, et al. Diabetes mellitus and abnormal glucose tolerance development after gestational diabetes: A three-year, prospective, randomized, clinical-based, Mediterranean lifestyle interventional study with parallel groups. Clini Nutr 2015; 34:579-585.

- Metzger BE, Coustan DR, Organizing Committee. Summary and recommendations of the fourth international workshop-conference on gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 1998; 21:161.

- Majeed A, El-Sayed AA, Khoja T, et al. Diabetes in the Middle-East and North Africa: An update. Diabetes Res Clin Practice 2014; 103:218-222.

- Alharthi AS, Althobaiti KA, Alswat KA. Gestational diabetes mellitus knowledge assessment among Saudi women. Macedonian J Med Sci 2018; 6:1522.

- Sacks DA, Hadden DR, Maresh M, et al. Frequency of gestational diabetes mellitus at collaborating centers based on IADPSG consensus panelâ??recommended criteria: The Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study. Diabetes Care 2012; 35:526.

- Alfadhli EM, Osman EN, Basri TH, et al. Gestational diabetes among Saudi women: prevalence, risk factors and pregnancy outcomes. Annals Saudi Med 2015; 35:222-230.

- Zhu Y, Zhang C. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and risk of progression to type 2 diabetes: A global perspective. Curr Diabetes Rep 2016; 16:1.

- Hummel S, Much D, Rossbauer M, et al. Postpartum outcomes in women with gestational diabetes and their offspring: POGO study design and first-year results. Rev Diabetic Studies 2013; 10:49.

- Linné Y, Barkeling B, Rössner S. Natural course of gestational diabetes mellitus: long term follow up of women in the SPAWN study. Int J Obstetr Gynaecol 2002; 109:1227-1231.

- Li Z, Cheng Y, Wang D, et al. Incidence rate of type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 170,139 women. J Diabetes Res 2020; 2020.

- Buchanan TA, Xiang AH. Gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Investigation 2005; 115:485-491.

- Cho GJ, Park JH, Lee H, et al. Prepregnancy factors as determinants of the development of diabetes mellitus after first pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016; 101:2923-2930.

- Barbour LA, McCurdy CE, Hernandez TL, et al. Cellular mechanisms for insulin resistance in normal pregnancy and gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007; 30:112-119.

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2014; 37:81-90.

- Ballas J, Moore TR, Ramos GA. Management of diabetes in pregnancy. Curr Diabetes Rep 2012; 12:33-42.

- American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care 2021; 44:111-124.

- Plows JF, Stanley JL, Baker PN, et al. The pathophysiology of gestational diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci 2018; 19:3342.

- Kahn SE, Cooper ME, Del Prato S. Pathophysiology and treatment of type 2 diabetes: perspectives on the past, present, and future. Lancet 2014; 383:1068-1083.

- Wu Y, Ding Y, Tanaka Y, et al. Risk factors contributing to type 2 diabetes and recent advances in the treatment and prevention. Int J Med Sci 2014; 11:1185.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Appendices

| 1. Are you a female? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| If ‘No’ do not continue. Please submit the questionnaire. Otherwise proceed to next question (No. 2) |

| 2. Are you Married or once married? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| If ‘No’ do not continue. Please submit the questionnaire. Otherwise proceed to next question (No. 3) |

| 3. Have you become pregnant anytime? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| If ‘No’ do not continue. Please submit the questionnaire. Otherwise proceed to next question (No. 4) |

| 4. Have you suffered from diabetes only during pregnancy? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| 5. Age (years) |

| A. <30 years |

| B. 30-50 years |

| C. >50 years |

| 6. Nationality |

| A. Saudi |

| B. Non-Saudi |

| 7. Residence city |

| A. Taif |

| B. Other |

| 8. Educational level |

| A. Middle school or less |

| B. High school |

| C. Bachelor’s degree |

| D. Master’s degree/PhD |

| If yes, answer the following questions. |

| 9. What was your age when you suffered from gestational diabetes? |

| �����.. years. |

| 10. What was your weight during pregnancy when you suffered from gestational diabetes? |

| �����.. Kg |

| 11. What was your height during pregnancy when you suffered from gestational diabetes? |

| �����.. cm |

| 12. What was the weight of your child when he or she was born after you suffered from gestational diabetes? |

| A. <2000 grams (<2 kg) |

| B. 2000- 3000 grams |

| C. 3000-4000 grams |

| D. >4000 grams |

| 13. Does your child suffered from any congenital abnormalities when she was given birth after you have suffered from gestational diabetes? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| 14. Were you suffering from hypertension during pregnancy when you gestational diabetes ? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| 15. Do you have a family history of Diabetes (father or mother is diabetic)? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| 16. Have you had any history of stillbirth (fetal death at or after 20 or 28 weeks of pregnancy)? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| 17. Have you suffered or suffering from polycystic ovary syndrome? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| 18. Have you had history of abortion? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| 19. Have you had history of preterm delivery for your child? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| 20. How many times had you given birth before pregnancy one you had gestational diabetes? |

| A. 1 time |

| B. 2 times |

| C. >2 times |

| 21. Have used insulin during pregnancy when you have suffered from gestational diabetes? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| 22. Have you smoked during your pregnancy? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| 23. Did you follow up gestational diabetes or check blood glucose after delivery? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

| 24. Do you still have diabetes after delivery? Or Are you suffering from Type 2 diabetes after delivery? |

| A. Yes |

| B. No |

Author Info

Afnan Mesfer Alotaibi1, Asma Abdullah Al-Dhasi2*, Rasan Faisal Almnjwami2, Ghadah Aedh Alzaidi2 and Arwa Aloush Almutairi2

1Lecture in Taif University, Taif, Makkah, KSA2Medical Intern, Taif, Makkah, KSA

Received: 03-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. jrmds-22-76417; , Pre QC No. jrmds-22-76417(PQ); Editor assigned: 05-Oct-2022, Pre QC No. jrmds-22-76417(PQ); Reviewed: 20-Oct-2022, QC No. jrmds-22-76417(Q); Revised: 25-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. jrmds-22-76417(R); Published: 01-Nov-2022