Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 6

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Dietary Behaviors regarding Salt Intake among Adults in Mecca city, Saudi Arabia

Sarah Fouad Nabrawi1 and Nesrin Kamal Abd El-Fatah2*

*Correspondence: Nesrin Kamal Abd El-Fatah, Department of Nutrition, High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University, Egypt, Email:

Abstract

Background: Salt-related knowledge and behaviors data in Saudi Arabia is currently scarce. To establish a salt reduction program, data on the population's knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors towards salt is crucial. Therefore, we aimed to assess salt related knowledge, attitude, and behaviors (KAB), as well as their associations with demographic characteristics and knowledge and attitudes association with self-reported behaviors. Methods: A cross-sectional study was carried out on 270 Saudi Arabian adults, attending primary health care in Mecca city. Participants self-reported demographic, medical information, as well as completed a predesigned salt related KAB questionnaire. Results: Three quarters of participants (74.8%) reported poor knowledge. Only one fifth correctly identified adults recommended daily salt intake, and the Saudi diet's primary source of salt. Nearly half (45.7%) were concerned about food salt amount. Majority of participants (94.4%) had poor dietary salt behaviors that increase salt intake. Two thirds (68.5%) are often add salt during cooking, only 25.6% checking for salt label content and 38.9% buy no/low salt items. Knowledge was significantly higher among healthcare workers and younger adults, while positive attitude was significantly higher among females and participants with chronic diseases, frequent checking salt/sodium food labels, and higher rate of cutting down salt intake behavior. knowledge showed mild positive correlation with the attitude. Conclusions: this study results can be utilized to establish a baseline for salt intake KABs in Saudi Arabian adults and to track its changes over time. Community knowledge about dietary salt and their health hazards is low and raising awareness is crucial.

Keywords

Awareness, Practices, Salt reduction, Dietary sodium, Adults, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Habitual consumption of excessive salt may seem harmless, but it is linked to several health risks, which cause millions of premature deaths annually. The most common of these risks is high blood pressure, which alone accounts for an estimated 9.4 million deaths each year. The evidence for the health benefits of population- wide reduction in salt intake is strong. Indeed, salt reduction is one of the most cost-effective measures to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD) in both developed and developing countries [1]. Information on the population’s knowledge, attitudes and behaviors related to salt is an important step in the development and implementation of a salt reduction program.

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), also known as chronic diseases, tend to be of long duration and are the result of a combination of genetic, physiological, environmental and behaviors factors. The main types of NCDs are CVD, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes. CVDs are the number one cause of death globally, it accounts for most NCD deaths, or 17.9 million people annually, followed by cancers (9.0 million), respiratory diseases (3.9million), and diabetes (1.6 million). In Saudi Arabia CVDs account for nearly 50% of total deaths [2]. Cumulative evidence has shown that excess (sodium chloride) intake raises blood pressure (BP) [3], a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease [4] and increases risk of stomach cancer [5], a leading fatal cancer globally. Most cardiovascular diseases can be prevented by addressing behavioral risk factors such as tobacco use, salt intake, unhealthy diet and obesity, and physical inactivity using population-wide strategies.

People worldwide consume significantly more salt than they should. On average, people consume around 10 grams of salt per day globally. In the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) current salt intakes are very high, with an average intake of > 12 g per person per day in most countries, this is around double of WHO’s recommended level from all sources, including processed foods, ready-made meals and added salt when we prepare food at home [5-7]. WHO recommends intake less than 5 grams or under one teaspoon per day and for children aged 2 to 15 years WHO recommend even less salt than this, adjusted to their energy requirements for growth. Similarly, studies conducted in Saudi Arabia highlighted the problem of high sodium intake in the different region such as Aljouf region [8] and Eastern region [9]. This is likely to relate to the changing dietary habits in the Saudi community in recent years, including the practice of eating out, and the consumption of highly processed food and high-energy snacks [10]. In 2015, bread was confirmed to be the primary source of salt in the diets of individuals in the Gulf countries including. All these dietary habits were found to be associated with high dietary salt intake [11]. The main source of sodium in our diet is salt. The report of a joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation on ‘Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases’ recommends that sodium intake for adults should be <2 g/day (equal to 5 g of salt) [3]. Controlling the threat that salt poses to public health is a challenge facing developed and developing countries alike.

Lowering salt consumption is a practical action, which can save lives, prevent related diseases and reduce health-care costs for governments and individuals [3]. The overall goal of the global salt reduction push is a 30% relative reduction in average population salt intake towards the WHO-recommended level. This is the only nutrition-specific target and a core component of the Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013−2020, which aims to achieve a 25% reduction in premature mortality from avoidable noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) by 2025. The number of countries that are acting on salt reduction is increasing, but further action is critical to reduce the health consequences of eating too much salt. An important step in the development and implementation of a salt reduction program is to collect information on population salt intake; community knowledge, attitudes and behaviors related to salt use; and the sources of salt in the diet. Dietary salt studies on KAB assessed population knowledge of dietary salt recommendations, food sources, and diseases linked to high salt intake; attitudes toward salt reduction, health and salt intake concerns; and behaviors related to adding salt during cooking and at the table, as well as food purchasing decisions [12].

A metanalysis across twelve high income countries reported low KAB related to dietary salt intake [12]. Recent studies conducted in Oman, Sharjah, and Jordan recommended improving salt-related knowledge through health promotion campaigns [13-15]. Individuals are often unaware of the detrimental effects of salt on health and the Eastern Mediterranean Region including Saudi Arabia; is not an exception where the majority of salt consumed is hidden in processed foods [8-16]. There is currently a scarcity of information in Saudi Arabia about salt-related knowledge and behaviors. Hanbazaza et al. [17] Salt-related knowledge is limited and not linked to practices related to salt intake in Saudi adults.

These data are essential for planning a program that will target the area of greatest weakness in a country and which will have the greatest impact in terms of health and investment. There is, therefore, an obvious need for better understanding of the knowledge, attitudes and behaviors related to salt use in our community so that comprehensive public health interventions can be planned and implemented and thereby reduce dietary sodium intake and decrease the burden of cardiovascular diseases. To the best of our knowledge there have been no previous research studied the knowledge, attitudes and behaviors related to salt intake among Saudi Arabian population in mecca city. But these are all important questions that should be assessed. To study this gap in the literature, we aimed to determine knowledge, attitude and behaviors related to salt intake and health, KAB demographic patterns and to investigate the association of knowledge and attitudes with self- reported salt-related behaviors among Saudi Arabian adults in Mecca city.

Subjects and Methods

Design and study population

This cross-sectional study was conducted between October 1st and 28th 2021, on male and female adult (≥18) attending primary health care in Mecca city, Saudi Arabia. Using EPI-INFO 2002 software, a minimum required sample of 267 samples was determined, according to a previous study reported by Nasreddine et al in Lebanon 2014, that demonstrated the percentage of persons who agree that high salt added to food is definitely worsen health (77.6 %) [18]. with a precision of 5%, confidence level of 95% and an error of 0.05. A multistage stratified random sampling technique was used. In Mecca city, there are 18 primary health care centers; three of them were selected randomly. Primary health care centers attendees were selected for interview using random numbers for each day of data collection following inclusion criteria until the sample size was met. It is noteworthy to mention that the response rate was almost 100%. Research Ethics Committee of Taif Health Affairs, Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia approved this study (IRB. HAP-02-T-067, Number 165), and all necessary official approvals were fulfilled. All participants signed a written consent form before they answered questions and confidentiality was assured. Research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collection and study instruments

Participants self-reported demographic, medical information, as well as completed a predesigned questionnaire of knowledge, attitude, and behaviors (KAB) related to salt intake and health based on previously Published studies [18]. Few questions were added from another research [19]. Culture-specific modifications to examples of foods included in the questionnaire were done.

Demographic and medical characteristics

Demographic and medical characteristics were assessed including age; sex; marital status; education level; specialization in a health-related major; occupation; and income. In addition, history of chronic diseases and regular medications were collected. Participants also reported if they previously advised by a physician, nurse, or dietitian about the risks of a salt-rich diet and the need to moderate salt intake.

Knowledge

Assessment of knowledge was done by 34 questions related to dietary salt, which included relationship between high salt diet and overall health status (e.g., improves or worsens health) and can specific health conditions (e.g., high blood pressure, stroke, osteoporosis). In addition, the participants determined the relationship between salt and sodium, maximal limit for daily salt recommended for adults, main sources of salt in the Saudi Arabian diet, daily salt intake compares to the optimal amount recommended, and classified specific foods as high, medium, or low in salt/sodium. A score of (1) was given to the correct answer, and a score of (0) for wrong choice. The correct answer was reported beside each corrected choice. The total score on knowledge was calculated by combining correctly answered knowledge items of all knowledge questions (34 questions). Maximum possible score for the knowledge section was 34. Higher scores represented better knowledge. Knowledge was classified as "high", "medium" or "poor" according to the knowledge score obtained. High knowledge score was defined as ≥75th percentile, poor knowledge was defined as <60th percentile as, and moderate knowledge was defined as 60-< 75th percentile.

Attitude

Each respondent was asked a 10-item questions related to his/her attitude towards salt intake and health. Two of the questions addressed the participants' concerns about healthy eating and the quantity of salt in their diet. Responses include 5 points likert scale ranged from “not at all concerned” to “extremely concerned”. a score from 0 to 4 were given. Likewise, attitude assessment included a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree" in one block of eight items and a score from 0 to 4 were given. This block determined for example how crucial it is for the individual to limit the amount of salt added to foods and the amount of processed foods consumed. In addition, if an individual reduced the amount of salt in his/her diets his/her health would improve health. The final score was calculated by adding up the points obtained for the corresponding questions and the total score was 40, and the range was (0-40). Strongly agree (Extremely concerned) and agree (very concerned) were considered as positive attitude towards reducing salt intake, and strongly disagree and disagree were consider as negative attitude, and neither agree nor disagree presented as separate choice. Higher scores indicated a more positive attitude and lower score meaning more negative attitude. Participants were also asked who they thought was responsible for lowering population salt intake (e.g., government, food fast food chains, themselves) with four responses ranged from ‘not at all responsible, ’to ‘very responsible’. High attitude score was defined as ≥75th percentile, poor attitude was defined as <60th percentile as, and moderate attitude was defined as 60-< 75th percentile.

Behavior

Each respondent self-reported a 14-item questions related to his/her behavior towards salt intake and health. Four of the questions addressed the participants' Food label related behaviors (frequency of checking food labels; the frequency of looking at information of food labels affects purchasing decisions, the frequency of looking at the salt/sodium content on food labels during shopping and the frequency of the salt/sodium content shown on the food label affect purchasing a food item). Responses include 4 points likert scale ranged from “Often/always (correct answer=coded 1)” to “never do grocery shopping”. Likewise, Salt related behaviors were assessed by 9 items (e.g., Frequency of adding salt during cooking or at table, frequency of “trying to avoid eating processed and fast foods and the frequency of “trying to purchase no added salt” foods). Responses were categorized into often, sometimes, never and don’t know. a score of (1) was given to the Always/Often (correct), and a score of (0) for other responses (e.g., sometimes, never, rarely, don’t know). The final question inquired about participant’s trial to cut down salt eating (Yes/No), and their motivation or barriers to do or not. Behaviors final score for each item was calculated by adding up the points. The total score was 14, and the range was (0-14), with Higher scores indicated a more positive behavior towards reducing salt intake. The answers divided to two choices (often) and (not often). Similarly, High Salt related behaviors score was defined as ≥75th percentile, poor behaviors was defined as <60th percentile as, and moderate salt related behaviors defined as 60 ≤ 75th percentile.

The questionnaire was originally in English. Forward translation was initially performed by two native Arabic language bilingual translators, who are fluent in English. A backward translation was then performed by two native English speaker translators, fluent in Arabic and unfamiliar with the concepts of the scales. The back- translated English questionnaire was subsequently compared with the original English one, then inconsistencies between the two versions were solved. The questionnaire was pilot tested on a sample of 25 PHCs adult attendees before its adaptation to field work. A pilot study was carried out with the application of the full methodology and analysis of results. The method, the feasibility, and duration were assessed. Necessary changes were made and described.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM (SPSS) Statistics Version 25.0 software. The descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, were used for categorical variables; median and range were used for continuous variables after determining the normality using Shapiro test. The Shapiro-Wilk statistic test shows that knowledge, attitude, and behavior scores are not normally distributed (p<0.001, p<0.001, and p<0.001). Mann-Whitney U test was used to check for an association between continuous and dichotomous variables and The Kruskal Wallis test was used to compare multiple groups means of different scale scores. Spearman Rho correlation coefficients were determined to test the association between the continuous variables. Body Mass Index (kg/ m2) was computed based on the given weight and height and classified according to WHO guidelines. For all statistical tests, a significance level was determined below 5% and quoted as two-tailed hypothesis tests.

Reliability of variables included in the study questionnaire was assessed using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The knowledge questions (34 questions) proved a good reliability which was equal 0.789. The attitude questions (10 questions) proved a high reliability which was equal 0.849. The behavior questions (14 questions) proved a high reliability which was equal 0.816.

Results

Out of 270 participants, 180 (66.7%) were female and 90 (33.3%) were male. More than half 149 (55.2%) were aged 31-40 and 41-50, and 144 (53.2%) had technical degree. Only 46 (17.0%) were healthcare workers. More than two third 191 (70.7%) were married, and 107 (39.6%) had chronic illness. More than third 101 (37.7%) were overweight and 75 (28.0%) were obese; with BMI mean score 27.5 ± 6.0. The majority stated that they didn’t approach by dieticians 259 (95.9%) or advised by physicians 185 (68.4%) to reduce high salt consumption and make it medium, as shown in Table 1.

| Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 90 | 33.3 |

| Female | 180 | 66.7 | |

| Age (years) | 19-30 | 52 | 19.3 |

| 31-40 | 95 | 35.2 | |

| 41-50 | 54 | 20 | |

| ≥ 51 | 69 | 25.6 | |

| Healthcare workers | Yes | 46 | 17 |

| No | 224 | 83 | |

| Education | Writing and reading | 1 | 0.4 |

| Intermediate and lower | 7 | 2.6 | |

| High school | 53 | 19.6 | |

| Technical degree | 144 | 53.3 | |

| University bachelor's degree | 65 | 24.1 | |

| Occupation | Office work | 93 | 34.4 |

| Worker | 57 | 21.1 | |

| craftsmen | 14 | 5.2 | |

| Unemployed/ or housewives) | 105 | 38.9 | |

| Other | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Marital status | Single | 47 | 17.4 |

| Married | 191 | 70.7 | |

| Divorced and widowed. | 32 | 11.9 | |

| Chronic illness | Yes | 107 | 39.6 |

| No | 163 | 60.4 | |

| Type Chronic illness# | Heart disease | 2 | .1.8 |

| Stroke | 5 | 4.4 | |

| High blood pressure | 62 | 54.4 | |

| Heart attack | 7 | 6.1 | |

| Other | 38 | 33.3 | |

| Regular Drug intake | Yes | 128 | 47.4 |

| No | 142 | 52.6 | |

| Approached by a dietitian during PHC visits | Yes | 11 | 4.1 |

| No | 259 | 95.9 | |

| Previously advised by a physician, nurse or dietitian about the risks of a salt-rich diet and the need to moderate salt intake | Yes | 85 | 31.6 |

| No | 185 | 68.4 | |

| BMI | Underweight (<18.5) | 10 | 3.7 |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.99) | 84 | 31.1 | |

| Overweight (25–29.99) | 101 | 37.4 | |

| Obesity (≥30) | 75 | 27.8 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) Mean SD, 27.5 ± 6.0 Rang (min-max), (15.4-40.7) | |||

| #(n=114) Multiple response | |||

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics adults attending primary health care in Mecca centers (n=270).

Table 2 illustrates the detailed dietary salt-related knowledge among adults (≥ 18 years) attending primary health care in Mecca centers. The majority of the participants 202 (74.8%) had poor dietary salt-related knowledge level with average mean score 4.5 ± 16.4. The most correct information reported were; 188 (69.6%) “The salt worsen the health” and “Sandwiches (e.g. shawarma, fried chicken, hamburger) contain high salt level” equally, 261 (96.7%) “High salt caused high blood pressure”, then 232 (85.9%) “High salt intake caused fluid retention”, 175 (64.8%) “Sausages and Mortadella contain high salt level”,and 152 (56.3%) “Salt contains sodium”. While, the least correct answers reported by the study participants were; 32 (11.9%) “High salt consumption causes stomach cancer”, and 54 (20.0%) “5 grams (1 teaspoon) is the maximum daily amount of salt recommended for adults”. Also, the majority 233 (87.3%) reported that they don’t know about “Saudi initiative to reduce salt intake within the Saudi population”.

| Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The effect of the salt in your diet | Improves the health | 14 | 5.2 |

| Has no effect on health | 25 | 9.3 | |

| Worsen the health “correct” | 188 | 69.6 | |

| Don’t know | 43 | 15.9 | |

| The following health problems can be caused or aggravated by salty foods (correct) | High Blood Pressure | 261 | 96.7 |

| Stroke | 121 | 44.8 | |

| Osteoporosis | 61 | 22.6 | |

| Fluid Retention | 232 | 85.9 | |

| Heart attacks | 99 | 36.7 | |

| Stomach Cancer | 32 | 11.9 | |

| Kidney Disease | 194 | 71.9 | |

| The following health problems didn’t cause or aggravate by salty foods (correct) | Memory problem | 62 | 23 |

| Asthma ` | 90 | 33.3 | |

| Headache | 45 | 16.7 | |

| The maximum daily amount of salt recommended for adults | 3 grams (½ teaspoonful) | 49 | 18.1 |

| 5 grams (1 teaspoons) “correct” | 54 | 20 | |

| 8 grams (1 ½ teaspoons) | 22 | 8.1 | |

| 10 grams (2 teaspoons) | 20 | 7.4 | |

| 15 grams (2 ½ teaspoons) | 6 | 2.2 | |

| Don’t know | 119 | 44.1 | |

| Daily salt intake compares to the optimal amount recommended | More than the maximum recommended (correct) | 67 | 24.8 |

| About the right amount recommended | 121 | 44.8 | |

| Less than recommended | 36 | 13.3 | |

| Don’t know | 46 | 17 | |

| The relationship between salt and sodium | They are exactly the same | 43 | 15.9 |

| Salt contains sodium “correct” | 152 | 56.3 | |

| Sodium contains salt | 13 | 4.8 | |

| Don’t know | 62 | 23 | |

| The following foods considered to be medium in terms of salt/sodium content (150-250 mg/serving)- (correct answers) | Bread | 146 | 54.1 |

| Kapsaah or Vegetables ragouts | 142 | 52.6 | |

| The following foods considered to be low in terms of salt/sodium content: (1-150 mg/ serving) (correct) | Rice | 92 | 34.1 |

| Milk & Yoghurt | 139 | 51.5 | |

| Fruits juice | 73 | 27 | |

| Fresh carrot | 184 | 68.1 | |

| Cottage cheese, soft drinks | 61 | 22.6 | |

| The following foods considered to be high, in terms of salt/sodium content. (250-700) mg. (correct) | Albaik | 214 | 79.3 |

| Traditional pies | 77 | 28.5 | |

| Pizza | 123 | 45.6 | |

| Cheese spread | 165 | 61.1 | |

| French fries | 165 | 61.1 | |

| Sandwiches (e.g., shawarma, fried chicken, hamburger) | 188 | 69.6 | |

| ready to eat sauces | 211 | 78.1 | |

| Ketchup | 126 | 46.7 | |

| Salad dressings | 138 | 51.1 | |

| Roasted nuts | 156 | 57.8 | |

| Sausages and Mortadella | 175 | 64.8 | |

| Canned foods | 202 | 74.8 | |

| The main source of salt in the diet of Saudi people | Salt added during cooking | 141 | 52.2 |

| Salt added at table | 45 | 16.7 | |

| Salt in processed foods such as breads, cured meats, canned foods and takeaway (correct) | 59 | 21.9 | |

| Salt from natural sources such as vegetables and fruits | 5 | 1.9 | |

| Don’t know | 20 | 7.4 | |

| Awareness of Saudi initiative to reduce salt intake within the Saudi population | Yes | 34 | 12.7 |

| No | 233 | 87.3 | |

| A Knowledge score category | Poor<60% | 202 | 74.8 |

| Medium 60-75% | 65 | 24.1 | |

| High ≥ 75 % | 3 | 1.1 | |

| Knowledge score | Mean SD, 4.5 ± 16.4 Rang (min-max) (2.0-25.0) | ||

| Correct responses for knowledge questions are in bold | |||

Table 2: Dietary salt-related knowledge among adults attending primary health care in Mecca (n=270).

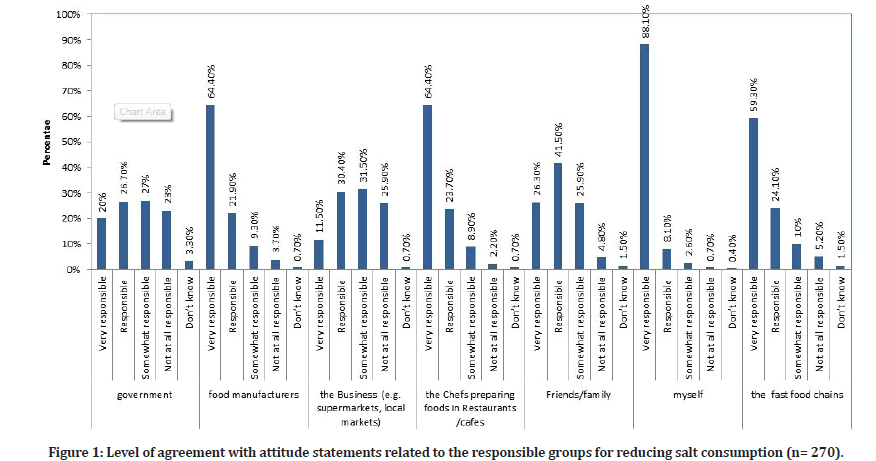

The result in Table 3 revealed positive attitude towards reducing dietary salt consumption with 30.03 ± 4.31 as the mean score out of total score 40. Where, 8 statements out of 10 showed high positive attitude (>70.0% for both very concerned and concerned). While the statement “I concerned about the aspect of the amount of salt in food” showed positive attitude on 45.7% of participants (extremely concerned (16.7%) and very concerned (29 %)). More than half of the studied adults (66%) stated that the present nutrition information on sodium/ salt is comprehensible. The most responsible group for reducing dietary salt intake reported by the study participants were; “food manufacturers” 86%, “the Chefs preparing foods in Restaurants /cafes ” 88.1%, and “the person himself” 96.2%, while the least responsible one was “the Business (e.g. supermarkets, local markets)” 41.9% (Figure 1).

| Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I concerned about the aspect of healthy eating | Extremely concerned | 40 | 14.8 |

| Very concerned | 66 | 24.4 | |

| Somewhat concerned | 138 | 51.1 | |

| Not very concerned | 25 | 9.3 | |

| Not at all concerned | 1 | 0.4 | |

| I concerned about the aspect of the amount of salt in food | Extremely concerned | 45 | 16.7 |

| Very concerned | 78 | 29 | |

| Somewhat concerned | 105 | 39 | |

| Not very concerned | 38 | 14.1 | |

| Not at all concerned | 3 | 1.1 | |

| My health would improve if I reduced the amount of salt in my diet | Strongly agree | 136 | 50.4 |

| Agree | 80 | 29.6 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 47 | 17.4 | |

| Disagree | 5 | 1.9 | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 | 0.7 | |

| I believe salt needs to be added to food to make it tasty | Strongly agree | 71 | 26.3 |

| Agree | 139 | 51.5 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 42 | 15.6 | |

| Disagree | 16 | 5.9 | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Himalayan salt, pink salt, sea salt and gourmet salts are healthier than regular table salt | Strongly agree | 86 | 31.9 |

| Agree | 112 | 41.5 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 59 | 21.9 | |

| Disagree | 11 | 4.1 | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 | 0.7 | |

| It is hard to understand sodium information displayed on food labels | Strongly disagree | 59 | 21.9 |

| Disagree | 119 | 44.1 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 59 | 21.9 | |

| Agree | 23 | 8.5 | |

| Strongly agree | 10 | 3.7 | |

| When eating out at restaurants/cafes/pubs, I find that lower salt options are not readily available or only in limited variety | Strongly agree | 100 | 37 |

| Agree | 113 | 41.9 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 46 | 17 | |

| Disagree | 7 | 2.6 | |

| Strongly disagree | 4 | 1.5 | |

| There should be laws which limit the amount of salt added to manufactured foods | Strongly agree | 128 | 47.4 |

| Agree | 95 | 35.2 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 40 | 14.8 | |

| Disagree | 4 | 1.5 | |

| Strongly disagree | 3 | 1.1 | |

| it is important for the us to reduce the amount of processed foods that he/she eats | Strongly agree | 167 | 61.9 |

| Agree | 85 | 31.5 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 16 | 5.9 | |

| Disagree | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Reducing your sodium intake is important to you | Strongly agree | 127 | 47 |

| Agree | 98 | 36.3 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 40 | 14.8 | |

| Disagree | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Strongly disagree | 3 | 1.1 | |

| Attitude score | Mean ± SD, 30.03 ± 4.31---Rang (min-max), (16-40.0) | ||

Table 3: Dietary salt-related attitudes among adults attending primary health care in Mecca centers (n=270).

Figure 1: Level of agreement with attitude statements related to the responsible groups for reducing salt consumption (n= 270).

Regarding the dietary salt-related behaviors, table 4 demonstrates that one third of the studied adults (36%) reported that what is on the food content label often affect whether or not they purchase a food item, 25.6% reported they often check food content labels during shopping, and only 13.3 % reported that they often look at the salt/sodium content on food labels during shopping. One third of the studied individuals (34.1%) use the ingredients list information on the food package to determine how much salt is in the product while 27.8% use the sodium level in the nutrition information panel to determine that. The majority of studied Saudis participants (185, 68.5%) are often add salt during cooking, and 67 (24.8%) individuals add salt on table, although 65.9% of the participants were trying to cut down on the amount of salt eating. The most common ways to lower the amount of salt in the diet reported amongst Saudis participants were observing food label to check the salt/sodium content of a food item” (40.4%) and asking to have a meal prepared without salt when eating out (51.1%). The main motivation of reducing dietary salt intake amongst Saudis participants was experiencing any change in health status, while the main barrier reported was the good taste of salted food reported by 158 (58.5%) individuals equally. Finally, as shown in table 4 most of the participants (225, 94.4%) had poor dietary salt-related behaviors.

| Variable | Knowledge Median (Range) | Attitude Median (Range) | Behavior Median (Range) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 16 (7-24) | 30 (16-39) | 5 (0.0-10) | P1=0.148 a |

| Female | 17 (2-25) | 32 (18-40) | 5 (0.0-12) | P2=0.040* a |

| Age | ||||

| 19-30 | 17(3-24) | 30(21-39) | 5(1-11) | P3=0.566 a |

| 31-40 | 18(7-25) | 30 (16-38) | 5(1-9) | P1=0.024* b |

| 41-50 | 16(4-24) | 30(20-40) | 5(0.0-12) | P2=0.123 b |

| ≥ 51 | 17(2-24) | 31(20-40) | 4(0.0-11) | P3=0.067 b |

| Healthcare workers | ||||

| Yes | 18(8-25) | 29 (18-39) | 5(0.0-9) | P1=0.006* a |

| No | 17(3-24) | 31(16-40) | 5(0.0-12) | P2=0.224 a |

| Education | ||||

| Intermediate and lower | 14(4-21) | 29 (22-33) | 5(1-11) | P3=0.727a |

| High school | 16(2-24) | 30(24-35) | 5(1-9) | P1=0.222 b |

| Technical degree | 17(5-24) | 31(16-40) | 5(0.0-12) | P2=0.345 b |

| University bachelor's degree | 18(4-25) | 30(23-40) | 5(0.0-9) | P3=0.880 b |

| Occupation | ||||

| Office work | 17(4-25) | 31 (16-24) | 5(1-12) | P1=0.430 b |

| Worker | 17(10-25) | 30(18-37) | 5(1-9) | P2=0.675 b |

| Craftsmen | 14(5-20) | 28(20-36) | 6(2-8) | P3=0.061 b |

| Unemployed/housewives | 17(2-24) | 31(19-40) | 5(0.0-11) | P1=0.536 b |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 17(8-24) | 30 (22-40) | 5(1-9) | P2=0.114 b |

| Married | 17(2-25) | 30(16-40) | 5(0.0-12) | P3=0.874 b |

| Divorced and widowed. | 16(4-23) | 32(20-39) | 5(0-9) | P1=0.943 a |

| Chronic illness | ||||

| No | 17(3-25) | 30 (18-39) | 5(0.0-12) | P2=0.010* a |

| Yes | 17(2-24) | 31(16-40) | 4(0.0-11) | P3=0.009* a |

| Drugs | ||||

| Yes | 17(2-24) | 31(16-40) | 4(0.0-11) | P1=0.793 a |

| No | 17(3-25) | 30 (18-39) | 5(0.0-12) | P2=0.166 a |

| BMI category | ||||

| Underweight | 16(5-24) | 30 (22-34) | 5(3-8) | P3=0.125a |

| Normal weight | 17(5-25) | 31(20-40) | 5(0.0-11) | P1=0.997 b |

| Overweight | 17(3-24) | 31(18-39) | 5(1-9) | P2=0.678 b |

| Obesity | 17(2-24) | 30(16-38) | 4(0.0-12) | P3=0.383 b |

| * Significant at p<0.05 , Significant findings are shown in bold | ||||

| P1: p value for salt related knowledge, P2: for attitude and P3: for salt related behaviors | ||||

| a: Mann-Whitney U test, b: Kruskal-Wallis Test | ||||

Table 4: The relation between dietary salt-related knowledge, attitude, behaviors, and demographics data among adults attending primary health care in mecca centers.

Table 4 illustrates the relation between Dietary salt- related knowledge, attitude, behaviors and demographics data. The level of knowledge was significantly higher among healthcare workers and younger adults than others (p=0.006 and 0.024 respectively). On the other hand, there was no significant association between knowledge level and other demographic data. (Table 5) positive attitude was significantly higher among females (median 17 vs. 16, p=0.040) and those with chronic illness (31(16-40) vs. 30(18-39), p=0.010). Contrastingly, dietary salt behaviors among those individuals were significantly lower among those with chronic illness (4(0.0-11) vs. 5(0.0-12), p=0.009). On the other hand, there was no significant association between attitude and behaviors score and other demographic characteristics of adults attending primary health care in Mecca centers.

| Variable | Knowledge Median (Range) | Attitude Median (Range) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Checking label for salt/sodium content | |||

| Often | 17(3-24) | 32(20-39) | P1=0.993 a |

| Not often | 17(2-25) | 30(16-40) | P2=0.02 a |

| Salt/sodium label content affects purchase decision | |||

| Often | 17(4-24) | 32(23-39) | P1=0.740 a |

| Not often | 17(2-25) | 30(16-40) | P2=0.001 a |

| Cutting down on salt | |||

| Yes | 17(2-25) | 31(16-40) | P1=0.249 a |

| No | 17(3-25) | 28(18-39) | P2=0.000 a |

| Often Purchased foods labelled “no or reduced added salt or sodium” | |||

| Often | 16(5-25) | 29(18-37) | P1=0.793 a |

| Not often | 17(2-24) | 31(16-40) | P2=0.166 a |

| * Significant findings (i.e., P<0.05) are shown in bold | |||

Table 5: Median knowledge and attitude scores (range) across the specific salt-related behavioral practices in a sample of Saudi adults.

There was a significant association between median attitude score and specific behaviors, where those who had higher median attitude score (a more positive attitude related to dietary salt intake) significantly checked food labels for salt/sodium content more often and this Salt/sodium label content affects their purchase decision more often (p=0.02 and 0.001 respectively). In addition, those who had a more positive attitudes towards reducing salt intake showed a significant higher rate of Cutting down on dietary salt intake behavior (p=0.000) (Table 5). Spearman’s Rank correlation depicted significant bivariate association between the dietary salt intake knowledge score and the attitude scores (salt related knowledge and attitude). Dietary salt knowledge showed mild positive correlation with the salt attitude score (rs=0.207, p=0.001), as shown in Table 6.

| Knowledge score | Behavior score | Attitude score | BMI (Kg/m2) | ||

| Knowledge score | rs | 1 | 0.019 | .207** | -0.044 |

| p | . | 0.755 | 0.001* | 0.468 | |

| Behavior score | rs | 0.019 | 1 | -0.072 | -0.105 |

| p | 0.755 | . | 0.241 | 0.085 | |

| Attitude score | rs | .207** | -0.072 | 1 | 0.034 |

| p | 0.001* | 0.241 | . | 0.577 | |

| BMI Kg/m2) | rs | -0.044 | -0.105 | 0.034 | 1 |

| p | 0.468 | 0.085 | 0.577 | . | |

| **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). | |||||

| *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). | |||||

| Â p value is illustrated in italic format | |||||

| *Significant findings (i.e., P<0.05) are shown in bold | |||||

Table 6: Spearman's rank correlation matrix of the bivariate variables in relation to dietary salt behaviors score.

Discussion

The current study explored dietary salt-related knowledge, attitude, and self-reported behaviors in a sample of Saudis adults attend PHCCs in Macca City, Saudi Arabia and investigates the association of socio- demographic factors, knowledge and attitudes with self-reported salt-related behaviors. This study reported limited salt-related knowledge as well as poor practices toward reducing salt intake. Majority of participants (94.4%) had poor dietary salt behaviors that increase salt intake. This finding was in consistent with those reported from Saudi Arabia [17], Lebanon [18] and high- Income Countries [12].

It is worth to note that, the majority of the participants were aware that excessive salt consumption can have negative health consequences, including elevated blood pressure and fluid retention. Compatible with previous research [18], many participants were unaware of the other health illnesses that are possibly associated with high sodium intake like stomach cancer. This was consistent with the only previous study on salt related KAB among Saudis. Most participants in the study were ignorant of the maximum salt intake, while the majority also believed that their daily salt intake would be equal to or below the recommended threshold point. Similarly, the findings are consistent with those reported by Nasreddine et al. among Lebanese costumers [18], Grimes et al. [20]. Amongst adults a recent meta- analysis reported the same findings [12]. In line with the study low level of salt related knowledge among the study participants, most of them were unaware about Saudi initiative to reduce salt intake within the Saudi population Further, The results also revealed that most participants had average awareness of the primary popular foods in Arab countries, that provide salt in the diet such as bread, traditional pies, pizza, Salad dressings, and roasted nuts as a high source of salt food items. Less than a quarter recognizing processed foods as the main sources of salt intake. Similar result was reported in Lebanon and Sharjah investigating attitudes, knowledge, and behavior related to salt consumption [14,18]. These data suggest that Saudis participants are unaware that some of the most common sources of dietary salt are 'hidden' in regular foods. This could explain why nearly half of the study participants showed concern about the amount of salt in their diet.

The current study highlighted the Dietary salt-related behaviors among adults attending primary health care centers in Mecca. Despite the fact that most of participants were adding salt on table and while cooking, more than half of participants reported they were trying to cut down on the amount of dietary salt intake. The main explanation for this that they reported that the common constraint to reducing salt intake was that salt makes food taste delicious. Most of the participants had poor dietary salt-related behaviors. This was consistent with other studies conducted in Arab countries [13-15,17,18]. Concerning Food label related behaviors, while a quarter of the participants said they often read food labels, only 13.3 percent said they check specifically for salt levels. It is worth mentioning that most of the participants reported that the salt content on the label doesn’t affect their decision to purchase the product. These findings are higher than the results reported by Nasreddine et al and Webster J et al [18,21]. This could be explained by higher rate of participants (59.4%)) reported that salt- related label information is not comprehensible lead to difficulty in using and interpreting labeled sodium information. Similar result was reported in Lebanon study (62.2%) [18].

The findings of this research revealed that higher salt- related knowledge and more positive attitude to reduce salt intake were significantly higher among younger adults. This was in contrast with previous studies that showed that older people demonstrate higher levels of salt-related knowledge and awareness, where the prevalence of diseases increases with increasing age and nutritional counselling is more common among elderly than among younger adults [18,22]. Similarly, positive attitude was significantly higher among participants with chronic diseases and knowledge was also significantly higher among healthcare workers. Both health care workers and individuals with chronic diseases are more health and nutrition conscious and exposed more to dietary and nutritional counseling. It is noteworthy that in the current study, female sex was identified as a characteristic associated with a more beneficial attitude towards salt reduction. This was consistent previous studies stating women to have higher salt-related knowledge and attitudes [17,23]. A review published in 2018 revealed similar conclusions. Females made a stronger attempt to minimize sodium levels by limiting salt intake and purchasing less fast food, according to McKenzie B et al review [23]. In fact, women were shown to be more health concerned than men in general and were more inclined to read and follow dietary advice. However, in the current study, there was no significant association reported between salt related KAB and participant’s marital status. This was consistent with the findings of Othman et al. [24] However, contrary to previous findings [25], we did not observe any significant relationship between educational level and salt related KAB. Higher BMI among the studied participants in this study wasn’t linked to better salt related behaviors. In a study conducted in China, individuals who knew they were at an elevated risk of health repercussions due to high sodium intake were more likely to prioritize salt reduction [22].

Interestingly, In the current study positive attitude towards salt reduction was significantly higher among those with more frequent checking salt/sodium food labels, and higher rate of cutting down salt intake behavior, this means that participants who reported positive attitude towards salt reduction adopt favorable salt-related behaviors. this could be explained with the theory of planned behavior where individual behaviors are affected by knowledge and attitudes. These results are in line with Grimes, CA et al [20] and Nasreddine et al [18], where knowledge and attitudes played an important role in prediction of sodium intake. However, this study couldn’t establish a relationship between salt intake related knowledge and behaviors, and we found that dietary salt behaviors were significantly lower among those with chronic illness who supposed to be more knowledgeable. This contradicts previous research in this point, where people aware of the hazardous effects of high dietary salt on health were more likely to report cutting down on salt and people aware of the relationship between salt and sodium were more likely to modify their food purchase decision based on salt label content [18]. Several previous studies also reported that salt reduction education, was effective in improving salt- related behavioral practices [26]. For instance, raising awareness about the maximal limit of daily salt intake and the main source of salt in proceeds foods can help in making better choices when purchasing processed foods and ease the understanding of nutrition information on food labels. Also, raising the consumer’s awareness and emphasizing on processed foods as the main source of dietary salt put pressure on the food industry to take actions towards decreasing the sodium content of food. In agreement with our findings, some studies reported that increasing salt related awareness have no impact on self-reported practices [17,27,28]. Similarly, previous reviews suggest good salt related awareness alone are unlikely to have a substantial impact on population salt intake behaviors [12,17,29]. The relationship between salt-related knowledge and practices is complex, and it can be influenced by a variety of factors such as demography, education levels, economic status, the environment, and culture. Complementary to knowledge availability of a healthier food supply and environments that support lower salt intake such as reformulation to reduce salt content in foods, fiscal, trade or healthy food procurement policies are needed to ensure a substantial and sustained impact [29,30].

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study presented a crucial insight of salt-related knowledge, attitude, and behaviors among a sample of Saudi Arabian adults, and revealed poor levels, emphasizing the crucial need to develop effective, evidence-based salt-reduction campaigns on dietary salt recommendations, identify main sources of sodium in the Saudi diet, and guide national policies. Additionally, increasing consumer knowledge and highlighting processed foods as the primary source of dietary salt exert pressure on the food industry to try to limit sodium content in products. future studies addressing the barriers to salt reduction are needed, as well as support for present initiatives in Saudi Arabia to reduce salt while maintaining taste and acceptance. Longitudinal and interventional studies are recommended to observe changes over time and to assess the impact of raising community awareness on salt reduction. There are a number of strengths of this study, including the inclusion of appropriate sample size, our sample was recruited randomly, covering multiple PHCs in mecca city. In addition, research on KAB among male and female Saudi adults is limited. Targeting adult age is very crucial as high salt consumption and health impact tends to be greater for populations in this life stage. However, there are also some limitations to consider. Firstly, all data are self-reported which may involve recall bias and may be different from actual behavior. Finally, because the study was conducted at a single city in Saudi Arabia, more caution should be used when extrapolating the findings to other communities. Multisector collaboration between the food manufacturers, health agencies and government are required to improve public awareness and to reduce the salt content of foods to decrease population salt consumption in Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank residents, colleagues, and administrative staff at Mecca Preventive Medicine Program, Public Health Administration, Mecca Health Affairs, Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia, for their continuous support.

Author Contributions

Sarah Nabrawi and Nesrin Kamal Abd El Fattah designed the Study proposal and questionnaire and collect research data. Nesrin Kamal Abd El Fattah and Sarah Nabrawi share in article writing. Nesrin Kamal Abd El Fattah analyzed data.

Financial Support

Self-funded.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Taif Health Affairs, Ministry of Health, and Saudi Arabia approved this study (IRB. HAP-02-T-067, 653). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Data Availability Statement

Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- He FJ, MacGregor GA. Salt reduction lowers cardiovascular risk: Meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet 2011; 378:380-382.

- https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241514620

- He FJ, Li J, Macgregor GA. Effect of longer term modest salt reduction on blood pressure: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Br Mrd J 2013; 346:1325.

- Aburto NJ, Ziolkovska A, Hooper L, et al. Effect of lower sodium intake on health: systematic review and meta-analyses. Br Med J 2013; 346:1326.

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010; 127:2893-917.

- https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/94384/9789241506236_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/salt-reduction

- Alkhunaizi AM, Al Jishi HA, Al Sadah ZA. Salt intake in eastern Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J 2013; 19:915-918.

- Saeedi MY, AlMadani AJ, Alsafi YH, et al. Estimation of Sodium and Potassium Intake in 24-Hours Urine, Aljouf Region, Northern Saudi Arabia. Chronic Dis Int 2017; 4:1026.

- Moradi-Lakeh M, El Bcheraoui C, Afshin A, et al. Diet in Saudi Arabia: Findings from a nationally representative survey. Public Health Nutr 2017; 20:1075-81.

- Alhamad N, Almalt E, Alamir N, et al. An overview of salt intake reduction efforts in the gulf cooperation council countries. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2015; 5:172-1777.

- Bhana N, Utter J, Eyles H. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to dietary salt intake in high-income countries: A systematic review. Curr Nutr Rep 2018; 7:183-197.

- Al-Mawali A, D'Elia L, Jayapal SK, et al. National survey to estimate sodium and potassium intake and knowledge attitudes and behaviors towards salt consumption of adults in the Sultanate of Oman. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e037012.

- Cheikh Ismail L, Hashim M, H Jarrar A, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice on salt and assessment of dietary salt and fat intake among university of Sharjah students. Nutrients 2019; 11:941.

- Alawwa I, Dagash R, Saleh A, et al. Dietary salt consumption and the knowledge, attitudes and behavior of healthy adults: A cross-sectional study from Jordan. Libyan J Med 2018; 13:1479602.

- Brown IJ, Tzoulaki I, Candeias V, et al. Salt intakes around the world: implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol 2009; 38:791-813.

- Hanbazaza MA, Mumena WA. Knowledge and practices related to salt intake among Saudi adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17:5749.

- Nasreddine L, Akl C, Al-Shaar L, et al. Consumer knowledge, attitudes and salt-related behavior in the Middle East: The case of Lebanon. Nutrients 2014; 6:5079.

- Grimes CA, Kelley SJ, Stanley S, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to dietary salt among adults in the state of Victoria, Australia 2015. BMC Public Health 2017; 17:532.

- Grimes CA, Riddell LJ, Nowson CA. Consumer knowledge and attitudes to salt intake and labelled salt information. Appetite 2009; 53:189-194.

- Webster JL, Li N, Dunford EK, et al. Consumer awareness and self-reported behaviours related to salt consumption in Australia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2010; 19:550-554.

- Zhang J, Xu AQ, Ma JX, et al. Dietary sodium intake: Knowledge, attitudes and practices in Shandong Province, China, 2011. PloS One 2013; 8:e58973.

- McKenzie B, Santos JA, Trieu K, et al. The science of salt: A focused review on salt-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviors, and gender differences. J Clin Hypertens 2018; 20:850-866.

- Othman F, Ambak R, Siew Man C, et al. Factors associated with high sodium intake assessed from 24-hour urinary excretion and the potential effect of energy intake. J Nutr Metabol 2019; 2019.

- Sarmugam R, Worsley A, Wang W. An examination of the mediating role of salt knowledge and beliefs on the relationship between socio-demographic factors and discretionary salt use: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013; 10:25.

- Santos JA, McKenzie B, Rosewarne E, et al. Strengthening knowledge to practice on effective salt reduction interventions in low- and middle-income countries. Curr Nutr Rep 2021; 10:211-225.

- Rubinstein A, Miranda JJ, Beratarrechea A, et al. Effectiveness of an mHealth intervention to improve the cardiometabolic profile of people with prehypertension in low-resource urban settings in Latin America: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016; 4:52–63.

- Trieu K, Ieremia M, Santos J, et al. Effects of a nationwide strategy to reduce salt intake in Samoa. J Hypertens 2018; 36:188-198.

- Trieu K, Neal B, Hawkes C, et al. Salt reduction initiatives around the world: A systematic review of progress towards the global target. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0130247.

- McLaren L, Sumar N, Barberio AM, et al. Population-level interventions in government jurisdictions for dietary sodium reduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 9:CD010166.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Author Info

Sarah Fouad Nabrawi1 and Nesrin Kamal Abd El-Fatah2*

1Saudi Board of Preventive Medicine, Ministry of Health, Makkah, Saudi Arabia2Department of Nutrition, High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University, Egypt

Citation: Sarah Fouad Nabrawi, Nesrin Kamal Abd El-Fatah, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Dietary Behaviors regarding Salt Intake among Adults in Mecca city, Saudi Arabia, J Res Med Dent Sci, 2022, 10 (6):09-20.

Received: 21-May-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-64556; , Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-64556 (PQ); Editor assigned: 23-May-2022, Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-64556 (PQ); Reviewed: 06-Jun-2022, QC No. JRMDS-22-64556; Revised: 10-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-64556 (R); Published: 17-Jun-2022