Research - (2020) Volume 8, Issue 4

Involvement of Mothers in Adolescent Sexuality Education in Makurdi Metropolis, Benue State, Nigeria

Ishaku Ara Bako1*, Jeremiah Odu Agweye1, Onyemocho Audu1 and Senol Dane2

*Correspondence: Ishaku Ara Bako, Department of Epidemiology and Community Health, College of Health Sciences, Benue State University, Makurdi, Nigeria, Email:

Abstract

Introduction: Adolescents are vulnerable to many sexual and reproductive health challenges. Sexuality education at home has been identified as a primary source of reliable sexuality education for adolescents. This study was aimed at assessing the prevalence of and factors associated with mothers-adolescent sexuality communication in Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria.

Method: The study was a community based cross-sectional study design conducted among randomly selected 377 consenting mothers of adolescents in Makurdi, Nigeria. Data collection was done using structured, interviewer administered questionnaires and analysis was done using SPSS version 23. Multiple logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with motheradolescent communication in sexuality.

Results: Majority of the respondents, 256 (94.4%) believed sex education is important and 354 (93.9%) support its introduction into the school curriculum. 324 (85.9%) had sexuality education with their adolescents. Most of the mother-adolescent discussions were initiated by the mothers (75.9%), 6.4% were by the child and 3.7% by the fathers and mostly on discussions were on abstinence (76.6%). Factors associated with more likelihood of having mother-adolescent communication in sexuality were older age, 5.5 (2.46-12.24) and educational status, 3.1 (1.51-6.61) while polygamous family setting, 0.18 (0.05-0.43) and lack of previous discussion in sexuality with their own mothers, 0.3 (0.13-0.51) were less likely to communicate with their adolescents on sexuality.

Discussion: A relatively high proportion of the respondents had good perception and have had communicated with their adolescents on sexual and reproductive health issues, which may be attributable to high educational attainment of our respondents.

Conclusion: Majority of the mothers communicate with their adolescent children on sexuality related issues. Most of the discussions were on abstinence. Factors associated with communication with adolescent children were age of respondents, educational attainment, family type and whether the respondents had sexuality education with their own parents were less likely to do so. The knowledge and skills of parents should be built up to improve the contents of mother-adolescent discussion on sexuality.

Keywords

Adolescents, Sexuality, Education, Mother-adolescent communication

Introduction

Adolescents are estimated to be nearly 1.2 billion, with over 80% of them residing in developing counties [1]. Most of these young people reach sexual maturity before having mental/ emotional maturity [2,3]. Young persons are thus, often not able to appreciate the negative consequences of sexual behavior. Adolescents are thus vulnerable to many reproductive health challenges with its attending shortand long-term consequences such as sexually transmitted infections (including HIV/AIDS), unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortions early childbearing and dropping out of schools [4- 9]. It has thus become imperative to promote safe sexual behavior among young people [10]. World Health Organization (WHO) approved sexual health as one of five core aspects of the global reproductive health strategy in World Health Assembly of 2004 [1].

Sexuality education at home has been identified as a primary source of reliable sexuality education for adolescents [11]. Several studies have demonstrated that comprehensive adolescent sex education significantly improves delay in sexual initiation, lowering of number of sex partners, correct and prompt use of condom, use of modern contraceptives, reduction in adolescent pregnancy, HIV, and other sexually transmitted infections [4,12,13]. However, parent-adolescent communication on sexual health issues are often considered a taboo in most low-income countries. This, coupled with poor parental knowledge and skills to effectively communicate with their children, make the parents uncomfortable to discuss sexual and reproductive health issues with their children [5,11,14].

There are gaps in parent-adolescent sexuality communication in Nigeria despite the potential benefits and in Benue state where this study was carried out, there are limited available literatures on the concept. This study, which obtains information from mothers of adolescents in Makurdi, Benue state, would provide guide to educationists, health workers, and policy makers on how to improve communication between parents and their adolescent children on issues related to sexual and reproductive health. The aim of our study was to assess the perception and practices of mothers-adolescent sexuality communication in Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria.

Method

Study setting

The study was conducted in Makurdi, capital city of Benue State, Nigeria. Makurdi is one of the 23 Local Governments Areas (LGAs) in the state with an estimated population of 300,000 people. The LGA is made up of eleven council wards. It is home for the Tiv speaking people of the state, however people of different tribes of the country and beyond have come to settle in the town for various purposes. The major occupation of the citizen is agriculture. There are two universities, a federal and a state owned and a teaching hospital [15].

Study design

A cross-sectional community based descriptive study design was employed for the study.

Study population

The study population was mothers in Makurdi local government, Benue State, Nigeria. The inclusion criteria were mothers who had children aged 10 to 19 years who gave their consent to participate in the study. Mothers who were trained health professionals were excluded from the study [16].

Sample size determination

The minimum sample size was determined using the formula

N=z2pq/d2

Where: n=the minimum sample size, z=standard normal deviate at 95% confidence interval which corresponds 1.96, p=estimated proportion of mothers from previous studies (73.9%) [17].

q=complementary probability of P (=1–p)=0.33 and d=degree of precision (5%).

The sample size was 377 after adjusting for nonresponse.

Sampling technique

A multistage sampling technique was used in the selection of the participants. In stage one, out of a total of eleven council wards, six were selected using balloting. They include modern market, Akpa road/Wadata, Mbalagh, Fiidi, Agan and North Bank II. In stage two, systematic sampling was used to select household after proportionately allocating samples to each selected ward based on the number of households obtained from the National Population Commission. Based on proportionate allocation, the number of participants selected in each ward were as follows: Modern Market (44), Ankpa/Wadata (94), Mbalagh (59), Fiidi (70), North Bank II (51) and Agan (59). The last stage (stage 3) was selection of actual respondents. In each selected household, a woman who met the inclusion criteria was selected. In situation where the eligible participants in the household was more than one, simple random sampling was done by balloting to choose one.

Data collection

Data was collected using structured, interviewer administered questionnaires. Trained research assistants were used to collect the data. Pretesting was conducted with 38 households (10% of estimated sample), at Ikayongo, about 20 km away from Makurdi. Questions causing difficulty in the pretest were rephrased and corrected. The questionnaire obtained information on socio-demographic variables, knowledge of sex education, attitude, and practice of sex education. The period of questionnaire administration was 5 weeks.

Data analysis

Filled questionnaires were checked for completeness and cleaned. Data was analyzed with Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS version 23) software and presented in tables and charts. Chi-square (��2) test was used for test of association between the independent variables and the main outcome of the study, with statistical significance set at p value of 0.05. Multiple logistic regression was further performed for selected independent variables that have significant chi-square at < 0.05.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ethical committee of Benue University Teaching Hospital, Makurdi, before the study was conducted. An informed written consent was also obtained from Makurdi LGA Council Chairman and the entire selected ward/district heads. Verbal consent of the respondents was also sought.

Results

A total of three hundred and seventy-seven questionnaires were administered to the respondents, all questionnaires were correctly filled and returned, which implies that was a hundred percent (100%) rate. Majority of the respondents were between 30-35 years (140, 37.7%) while 98 (26.0%) were between the age range of 41-45 years. Majority of the respondents had tertiary education, 122 (32.4%), and 107 (28.4%) had Post graduate qualifications. The predominant ethnic group was Tiv 153, (40.6%), followed by Idoma127 (33.7%). Most of the respondents were Christians 359 (95.2%), and they had two or more adolescent children, 271 (71.9%) (Table 1).

| Variables | Age Group | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 30-35 years | 142 | 37.7 |

| 36-40 years | 64 | 17 | |

| 41-45 years | 98 | 26 | |

| 46-50 years | 39 | 10.3 | |

| 51-55 years | 27 | 7.2 | |

| 56-60 years | 7 | 1.9 | |

| Education | No education | 19 | 5 |

| Primary | 61 | 16.2 | |

| Secondary | 68 | 18 | |

| Tertiary | 122 | 32.4 | |

| Post-graduate | 107 | 28.4 | |

| Ethnic Group | Tiv | 153 | 40.6 |

| Idoma | 125 | 33.7 | |

| Others | 97 | 25.7 | |

| Religion | Christianity | 359 | 95.2 |

| Islam | 18 | 4.8 | |

| Number of adolescent children | One | 106 | 28.1 |

| Two or more | 271 | 71.9 |

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of the Respondents (n=377).

Majority of the respondents, 256 (94.4%) were of the opinion that sex education is important and 354 (93.9%) support its introduction into the school curriculum; 363 (96.3%) felt that both boys and girls should be given sexuality education, while 7 (1.9%) felt only boys and only girls should be given respectively. When asked about the ideal age to commence sexuality education for the adolescents, 246 (65.3%) were opined that 5-10 years was the ideal age, while 84 and 47(12.5%) felt the ideal age should be 11- 15 years and 16-20 years respectively. Majority of the respondents, 288 (76.4%) were of the opinion that both parents should be involved in providing sexuality education to the adolescent, while 66 (17.5%) were of the view that only mothers should do so (Table 2).

| Variables | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescent sexuality education is important | ||

| Yes | 356 | 94.4 |

| No | 21 | 5.6 |

| Would want sex education to be included in school curriculum | ||

| Yes | 354 | 93.9 |

| No | 17 | 4.5 |

| Undecided | 6 | 1.6 |

| Ideal Age (Years) to commence sexuality Education | ||

| 05-10 | 246 | 65.3 |

| 11-15 | 84 | 22.3 |

| 16-20 | 47 | 12.5 |

| Who should be given sex education | ||

| Boys only | 7 | 1.9 |

| Girls only | 7 | 1.9 |

| Both | 363 | 96.3 |

| Who should give sexuality education in the home | ||

| Both parents | 288 | 76.4 |

| Mother | 66 | 17.5 |

| Father | 7 | 1.9 |

| Others | 16 | 4.2 |

Table 2: Attitude towards sexuality education (n=377).

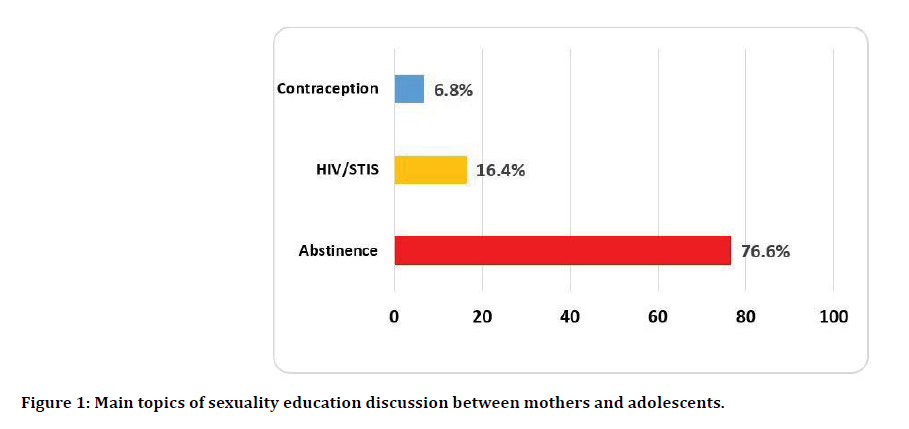

Regarding the practice of sexuality education, 324 (85.9%) have had sexuality education with their adolescent, with 150 (39.8%) and 148 (39.3%) doing so regularly and occasionally respectively. Most of the mother - adolescent discussions were initiated by the mothers (75.9%), 6.4% were by the child and 3.7% by the fathers. More than half, 217 (57.6%), of the respondents commenced their first communication with their adolescents when they were 5-10 years, 100 (26.5%) when the child was 11-15 years, while 7 (1.9%) started at 16-20 years. (Table 3) The main topics of mother-adolescent communication were on abstinence 76.6%, HIV and other STIs 16.4% and 6.8% discussed issues related to contraception (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Main topics of sexuality education discussion between mothers and adolescents.

| Frequency | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ever had mother-adolescent communication on sexuality | ||

| Yes | 324 | 85.9 |

| No | 53 | 14.1 |

| Who initiated the first discussion you had | ||

| Respondent (mother) | 286 | 75.9 |

| Child | 24 | 6.4 |

| Father | 14 | 3.7 |

| Age (years) of the child when first discussion was had | ||

| 05-Oct | 217 | 57.6 |

| 11-15 | 100 | 26.5 |

| 16-20 | 7 | 1.9 |

Table 3: Practice of mother adolescent communication on sexuality.

Table 4 presents the maternal factors associated with mother-adolescent communication on sexuality. Factors associated with more likelihood of having mother-adolescent communication in sexuality were older age, 5.5 (2.46-12.24) and educational status, 3.1 (1.51-6.61) while polygamous family setting, 0.18 (0.05-0.43) and lack of previous discussion in sexuality with their own mothers, 0.3 (0.13- 0.51) were less likely to communicate with their adolescents on sexuality.

| Variables | OR (95% C.I) | Significance (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 30-35 years | Ref | |

| > 35 years | 5.494 (2.465-12.244) | <0.001 | |

| Marital Status | Currently married | Ref | |

| Not currently married | 1.158 (0.467-2.871) | 0.752 | |

| Family Setting | Monogamous | ||

| Polygamous | 0.162 (0.061 - 0.426) | <0.001 | |

| Religion | Christianity | Ref | |

| Islam | 0.493 (0.147 - 1.656) | 0.252 | |

| Education | Secondary or lower | Ref | |

| Tertiary or PG | 3.161 (1.511 - 6.611) | 0.002 | |

| Did your parent discuss sexuality issue with you | Yes | Ref | |

| No | 0.266 (0.128 - 0.551) | <0.001 | |

Table 4: Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with mother-adolescent sexuality communication among mothers in Makurdi metropolis.

Discussion

This study was aimed at determining the attitude and practice related to –parent- adolescent communication on sexuality among mothers in Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria. Majority of our respondents are between 30-35 years and had tertiary education. When compared to previous studies, they are therefore relatively young and well educated [18-20]. The younger age may or may be an advantage to the respondents in terms of their ability to communicate with their children on sexuality. They are relatively inexperienced on sexual and reproductive health issues but may be better exposed to modern media and thus have more access to material son sexuality. An educated mother is expected to be able to communicate with her children better due to better knowledge and skills and ability to navigate through cultural barriers that hinder such communications.

Most of the respondents believed sexuality education is important (94.4%) and that they support its inclusion into the Nigeria’s education curriculum (93.9%). These findings agree with previous study conducted in Benin republic, where 90.8% of parents believed adolescent sexuality education was necessary [16]. In Ado Ekiti, Nigeria, 87.5% of parents said sex education should be taught in Secondary schools [21]. The good perception of mothers on adolescent sexuality education goes a long way to show that they realize the high risk these children are exposed to. This could also be as a result of the high educational attainments of our respondents.

The proportion of our respondents who have had communication with their adolescent on sexuality was 85.9%, which is relatively higher when compared with findings from previous studies. Studies among parents of adolescent in Lagos, Nigeria, found that 68.8% of them regularly discussed freely with their children while in Kano, Nigeria, 73.9% of mothers had communications with their daughters on sexual and reproductive issues [17-22]. Majority of the mothers in our study who communicated with Adolescents on sexuality concentrated on abstinence (76.6%), with only 16.4% and 6.8% including HIV/STIS and contraception respectively. Abstinence was the most preferred topic of discussion of most parents with adolescents in Ado Ekiti and Ghana [18,23]. Our study however disagreed with studies in Texas, USA only 27% preferred abstinence only sexuality education [21]. Other previous studies on contents of parental communication with adolescents found that the preferred topics in South West, Nigeria, were HIV prevention (51.9%), avoidance of pregnancy (40.9%) and abstinence (38.1%) [24] and in Enugu, Nigeria: pre-marital sex (49.8%), adolescent menstrual cycle (33.1%) and psychosocial changes (11.4%) [22].

This study found that 76.6% of respondents said both parents should communicate with their adolescent on sexuality, while 17.5% said only mothers and 1.9% thought only mothers should do so. This study also found that majority of the mothers (90.2%) were the ones who initiated the sexuality talk. Previous studies in China, Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia and Lagos and Southeastern Nigeria have all indicated that mothers were more likely than fathers to discuss with their adolescents [25-28].

From our study, factors associated with more likelihood of mother adolescent communication on sexuality were older age, monogamous setting, higher educational attainment and those whose own parents discussed sexuality with them. Previous findings on factors associated with parent child communication on sexuality vary. In Benin republic, University education was significantly associated with parental communication on adolescent sexuality [19]. Our study also agrees with a finding from Lagos hat older age of parents was significantly associated with likelihood of discussion on sexual health with their adolescent children [28]. In agreement with our study, a study in Ghana found that parents who did not receive sexuality education from their parents were less likely to communicate with their own adolescents on sexuality issues [17]. Our finding disagrees with a previous study in Lagos which found that younger parents were significantly more likely to discuss sexuality issues with their children. One key implication of our finding is the potential multiplier effect of current sexuality education effort in the home. Adolescents who are beneficiaries now would likely communicate with their children on sexuality issues in the future.

Limitation

This study has a few limitations. The respondents had relatively high educational attainment, most likely because it was conducted in Makurdi metropolis. The level of knowledge and skills of the respondents in relation to communication with adolescents on sexual and reproductive health may be higher than population of mothers in other parts of Benue state. The findings of this study may therefore not be a true representation of the mothers in the state. In addition, this study relied on respondents’ ability to recall previous events, thus subjecting the study to likelihood of recall bias.

Limitation

This study has a few limitations. The respondents had relatively high educational attainment, most likely because it was conducted in Makurdi metropolis. The level of knowledge and skills of the respondents in relation to communication with adolescents on sexual and reproductive health may be higher than population of mothers in other parts of Benue state. The findings of this study may therefore not be a true representation of the mothers in the state. In addition, this study relied on respondents’ ability to recall previous events, thus subjecting the study to likelihood of recall bias.

Conclusion

The study carried out among mothers in Makurdi metropolis showed that the mothers had positive attitude towards sexuality education and good practice of sexuality education. Mother who are advanced in age and had higher educational attainment were more likely to communicate with their adolescents on sexuality while those from polygamous family settings and those who did not had sexuality education with their own parents were less likely to do so.

Recommendations

The knowledge and skills of parents should be built up to improve the contents of motheradolescent discussion on sexuality. This can be achieved through sensitization in churches and mosques, Parent Teachers Association meetings, cooperative societies, health facilities etc. Sexuality education should be expanded beyond one that is abstinence - dominated to a more comprehensive one including aspects of cognitive (information), affective (feelings, values, and attitudes), and behavioral (communication, decision-making) and other skills. Parents should move from communications on sexuality that is essentially fear based to more positive communication that is more realistic, open, factual and without inhibitions.

References

- https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2020/Feb/un_2012_worldpopulationmonitoring_concisereport.pdf

- Houck C, Swenson R, Donenberg G, et al. Adolescents’ emotions prior to sexual activity and associations with sexual risk factors. AIDS Behav 2014; 18:1615-1623.

- Vandana AV, Apte AV, Budhwani C. Common psychological problems amongst adolescents and their mother’s awareness: A school-based study. J Evol Med Dent Sci 2014; 3:6031-6035.

- Ajuwon AJ. Benefits of sexuality education for young people in Nigeria. Understanding Human Sexuality Seminar Series 3. Africa Regional Sexuality Resource Centre 2005.

- Reniers RLEP, Murphy L, Lin A, et al. Risk perception and risk-taking behaviour during adolescence: The influence of personality and gender. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0153842.

- Eko JE, Osuchukwu NC, Osonwa OK, et al. Perception of students, teachers, and parents towards sexuality education in Calabar South LGA of cross river state, Nigeria. J Sociol Res 2013; 4:225-250.

- Adeomi AA, Adeoye OA, Adewole A, et al. Sexual risk behaviors among adolescents attending secondary schools in a Southwestern State in Nigeria. J Behav Health 2014; 3:176-180.

- Ugoji FN. Determinants of risky sexual behaviours among secondary school students in Delta State Nigeria. Int J Adolesc Youth 2014; 19:408-418.

- Kibret M. Reproductive health knowledge, attitude, and practice among high school students in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Afri J Repro Health 2003; 7:39-45.

- Breuner CC, Mattson G. Sexuality education for children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2016; 138:e20161348.

- Achu EA. The ambiguity surrounding parents’ role on sex education of their children: Nigeria experience. J Humanities Social Sci 2013; 18:52-57.

- Reis M, Ramiro L, de Matos MG, et al. The effects of sex education in promoting sexual and reprodcutive health in Portuguese university students. Procedia Social Behavioural Sci 2011; 29:477-485.

- Le Brun S, Omar HA. The importance of comprehensive sexuality education in adolescents. Pediatrics Faculty Publications, University of Kentucky 2015; 186.

- Hilakaan EI, Ogwuche JA. Wood business as a source of livelihood in Makurdi local government area, central Nigeria. Donnish J Ecology Natural Environ 2014; 2:6-11.

- Araoye MO. Research methodology with statistics for health and social sciences. Nathdex Publishers 2003; 115.

- Akinwale O, Adeneye A, Omotola D, et al. Parental perception, and practices relating to parent child communication on sexuality in Lagos, Nigeria. J Family Reprod Health 2009; 3:123-128.

- Achille OAA, Tonato BJA, Salifou K, et al. Parents’ perceptions and practices as regards adolescents’ sex education in the home environment in the city of Come, Benin in 2015. Reprod Syst Sex Disord 2017; 6:209.

- Titilayo O, Bose M, Olasumbo K, et al. Parents’ perception, attitude and practice towards providing sex education for adolescents in Eti-Osa local government area Lagos, Nigeria. Ife Psychologia 2019; 27:45-50.

- Tortolero SR, Johnson K, Peskin M, et al. Dispelling the myth: What parents really think about sex education in schools. J Appl Res Child 2011; 2:5.

- Esohe KP, PeterInyang M. Parents perception of the teaching of sexual education in secondary schools in Nigeria. Int J Innovative Sci Engineering Tech 2015; 2:89-99.

- Iliyasu Z, Aliyu MH, Abubakar IS, et al. Sexual and reproductive health communication between mothers and their adolescent daughters in northern Nigeria. Health Care Women Int 2012; 33:138-152.

- Nwangwu CN, Ezeah PC, Nwosuji EP, et al. Peoples’ perception of mother-daughter sexual communication patterns and adolescent girl’s reproductive health in Enugu North LGA of Enugu State, Nigeria. Int J Develop Management Rev 2017; 12:77-91.

- Manu AA, Mba CJ, Asare GQ, et al. Parent–child communication about sexual and reproductive health: Evidence from the Brong Ahafo region, Ghana. Reprod Health 2015; 12:16.

- Kunnuji MON. Parent-child communication on sexuality-related matters in the city of Lagos, Nigeria. Africa Development 2012; 37:41-58.

- Liu W, Edwards CP. Chinese parents’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices about sexuality education for adolescents in the family. Faculty Publications, Department of Child, Youth, and Family Studies 2003; 17.

- Aljoharah MA, Maha AA, Hafsa RM. Knowledge, attitude, and resources of sex education among female adolescent in public and private school in central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2012; 33:1001-1009.

- Dessie Y, Berhane Y, Worku A. Parent-adolescent sexual and reproductive health communication is extremely limited and associated with adolescent poor behavioral beliefs and subjective norms: Evidence from a community based cross-sectional study in eastern Ethiopia. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0129941.

- Asekun-Olarinmoye EO, Dairo MD, Abodurin OL, et al. Practice and content of sex education among adolescents in a family setting in rural southwest Nigeria. Int Q Community Health Educ 2012; 32:57-71.

Author Info

Ishaku Ara Bako1*, Jeremiah Odu Agweye1, Onyemocho Audu1 and Senol Dane2

1Department of Epidemiology and Community Health, College of Health Sciences, Benue State University, Makurdi, Nigeria2Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Nile University of Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria

Citation: Ishaku Ara Bako, Jeremiah Odu Agweye, Onyemocho Audu, Senol Dane, Involvement of Mothers in Adolescent Sexuality Education in Makurdi Metropolis, Benue State, Nigeria, J Res Med Dent Sci, 2020, 8 (4):36-42.

Received: 23-Apr-2020 Accepted: 30-Jun-2020 Published: 07-Jul-2020