Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 6

Implant removal surgeries in Orthopaedics: A Prospective Study

Saini Thirupathi* and Gattu Naresh

*Correspondence: Saini Thirupathi, Department of Orthopaedics, Prathima Medical College, India, Email:

Abstract

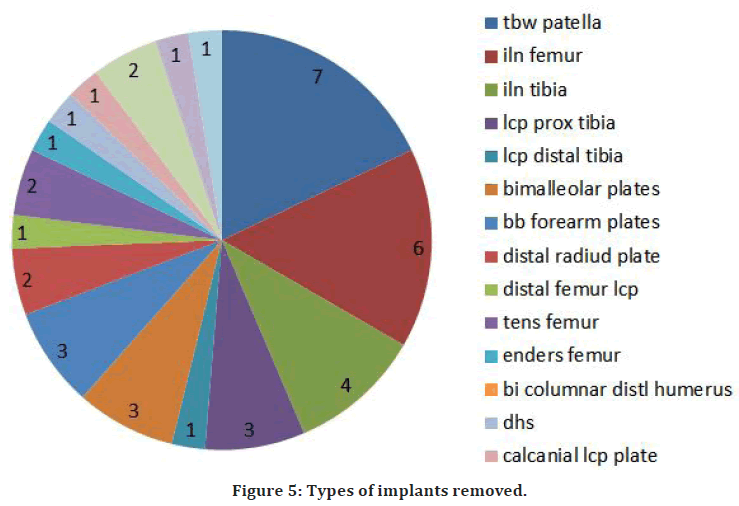

Background: It has been cumbersome to explain every patient in OPD who came for implant removal after union of fracture because implant ceases to be important and patients want to get rid of them. But as orthopedic surgeons we are somewhat reluctant in few cases because we know outcomes. From the patient’s point of view it has become a rejection factor in both professional and personal life. In order to remove the social stigma lets study on the various factors related to removal of implants. Methods: Data collected from patient records who are admitted for implant removal. Preoperative and postoperative X-rays were taken. Follow up was done until wound healing or new symptoms developed. Results: Total of 40 patients was studied which had predominantly males (77%).Uninfected (75%) being more than infected removals. Average interval between primary surgery and removal was 3years.Tension band wiring for the patella being the most common implant removed. Conclusion: Implant removals are not needed in all cases. Routine removal should not be performed in ‘asymptomatic’ patients It should be done in selected cases where there is definitive indication such as pediatric bones with open phases or an infected implant. Never do removals on patient’s force as most of the times we encounter failure to extract the implant. Always arrange for new implants and removal instruments keeping in mind non unions or refracture.

Keywords

Implants, X-rays, Primary surgery, OPD

Introduction

In recent era almost every bone can be fixed with internal fixation devices. The devices used in fixations are of various configurations and provide harmless behaviour to our internal organs. However, our society still follows the concept of natural healing by bone quacks without knowing the well-known scientifically proven implantation hardware. Worldwide, metal implants (e.g. plates, screws and nails) are used which are generally made of stainless steel or titanium alloys. After fracture healing has taken place an implant no longer has any function and the question arises whether the implant should be removed and if so, why and when? Though there are several presumed benefits of implant removal, like functional improvement and pain relief, the surgical procedure can be very challenging and may lead to complications such as neurovascular injury and refracture, whereas the expected outcome is not well determined yet. The medical indications for surgical removal of these metal implants are not well defined and a variety of viewpoints with large differences in opinions and practices between surgeons, countries, patients, anatomical locations and implant materials exist. In children, however, routine implant removal after fracture union is still standard procedure [1-8].

This study is aimed at determining the indications and other variables of orthopaedic hardware removals, performed at the Prathima Medical College, Nagunoor, Karimnagar.

Methods

This prospective study was conducted on patients admitted for implant removal in the Orthopaedic department at Prathima Medical College, Nagunoor, Karimnagar from September 2018 to May 2020. Patients who presented in the outpatient department (OPD) with hardware related problems and those demanded for removal were admitted. Patients with percutaneous K-wires, external fixators, Ilizarov fixators, joint prosthesis and titanium implants were excluded from our study.

During the time of admission, the possible risks of the operation and the possibility of non-favorable concerns were described to all patients. After admission, routine investigations were done on all patients to evaluate their fitness for surgery.

Postoperatively, the patients remained in the hospital for variable time subjecting on the indication of implant removal and the state of the wound. Longer duration of antibiotics was given in patients with infected hardware based on intra operative cultures. All the patients were strictly advised, at the time of discharge, to protect the limb for a flexible length of period as required. They were followed in the OPD for relief of symptoms, persistence of old complaints and development of new problems, and the data was recorded.

Results

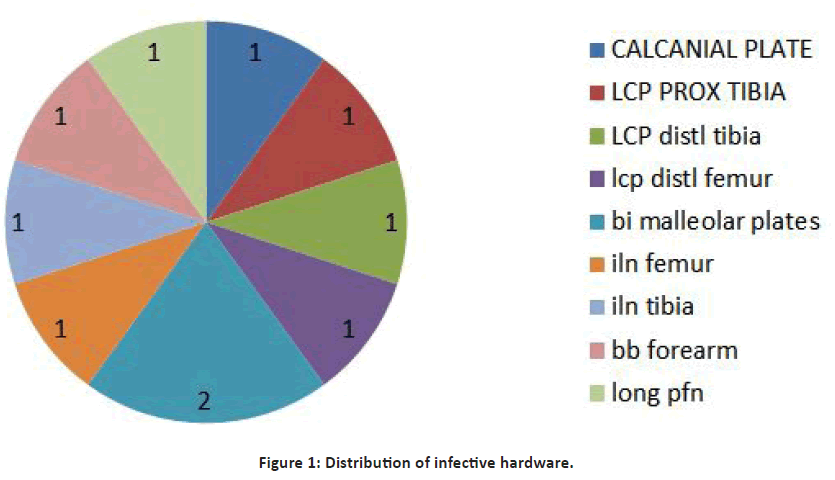

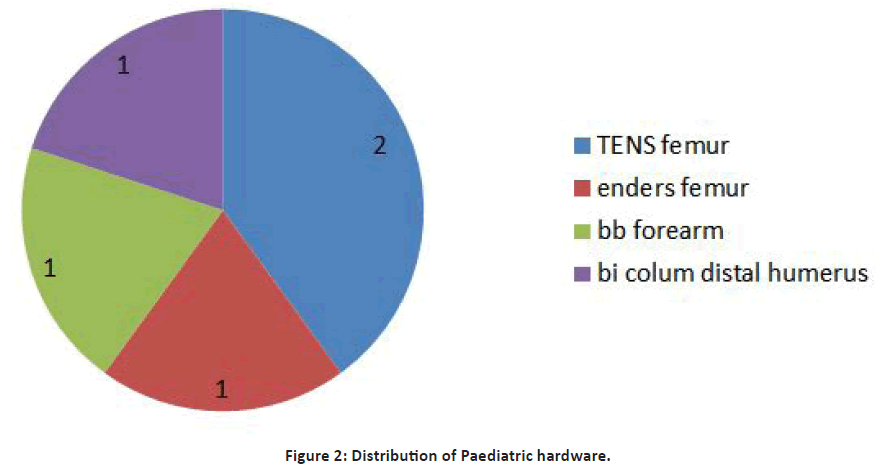

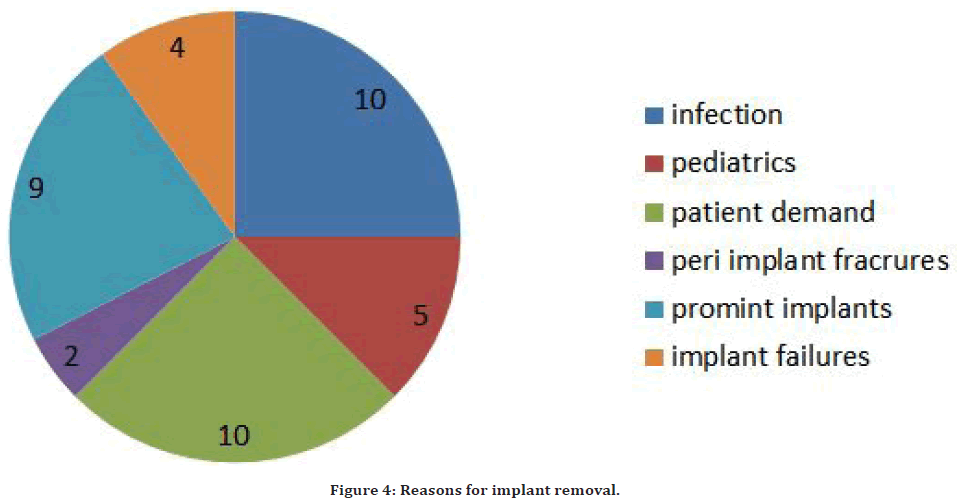

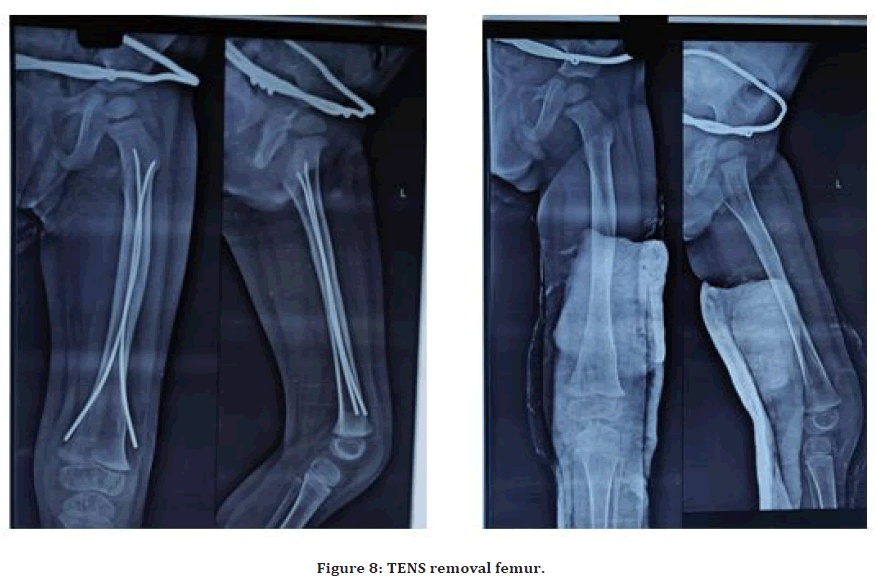

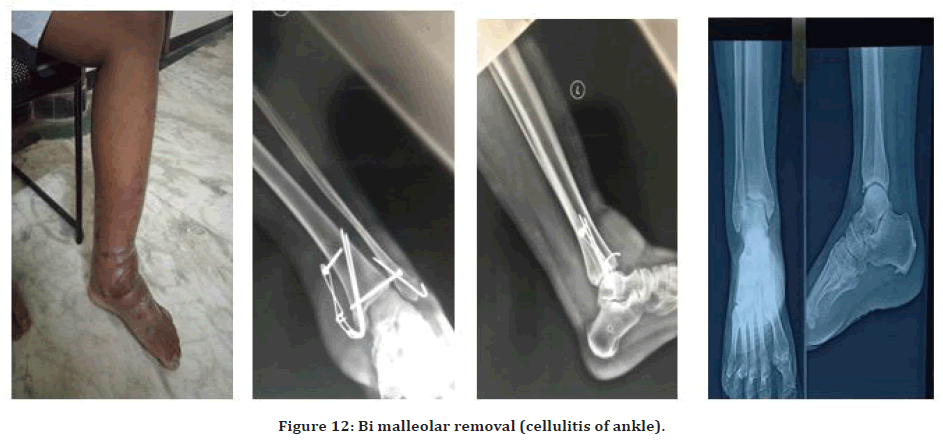

Over the period of our designed study, all the 40 patients fulfilling the criteria of selection were evaluated. All implants removed in our series were Indian made and were made of stainless steel. 31 were male (77%) and 9 were female (23%). Their mean age was 39.4 years. The reasons for removal of implants were found to lie in following categories: infected hardware, implant failure, elective (patient’s claim), change in treatment plan, peri implant fractures, prominent implant causing soft tissue irritation and Paediatric conditions. Ten patients out of 40 had demands for implant removal (25%). The mean duration of hospital stay in these patients was 5 days. No patient developed infection in their follow ups. 10 patients out of 40 (25%) needed implant removal due to development of infection at the implant site in constant period after Osteosynthesis. In this group, the implants most commonly removed were bimalleolar plates and screws. After the removal, infection subsided in all the patients. 2 (5%) patients required implant removal and modified by other implants (short PFN with shaft femur fracture converted to long PFN and Interlocking nail femur with supracondylar fracture converted to distal femur plating. In Paediatric population, 5 (12.5%) cases were included in our study group. These included 1 Enders nail femur, 2 femur TENS, 1 both bone forearm plate, 1 bi columnar plating for distal humerus fracture. No patient developed infection post implant removal in Paediatric age group.

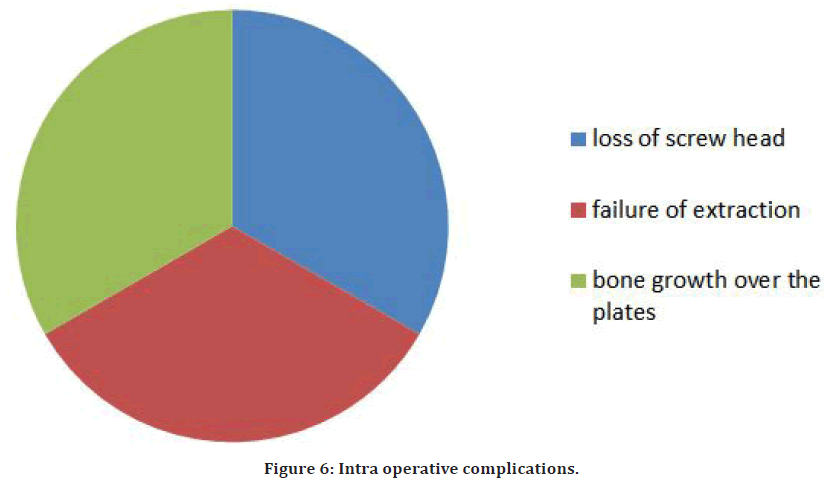

Intra op complications

9 Loss of screw head (cold welding) and slippage of screw driver in 2 cases of LCP’s.

9 Failure of extraction of ILN’s because of snug fit nature in 2 cases.

9 Bone growth over the plates with need of nibbling in 2 cases.

9 Average interval between primary surgery and removal of implant is 3yrs.

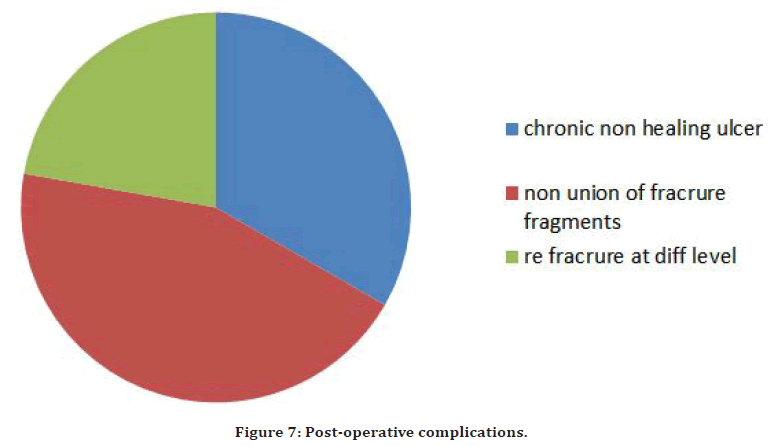

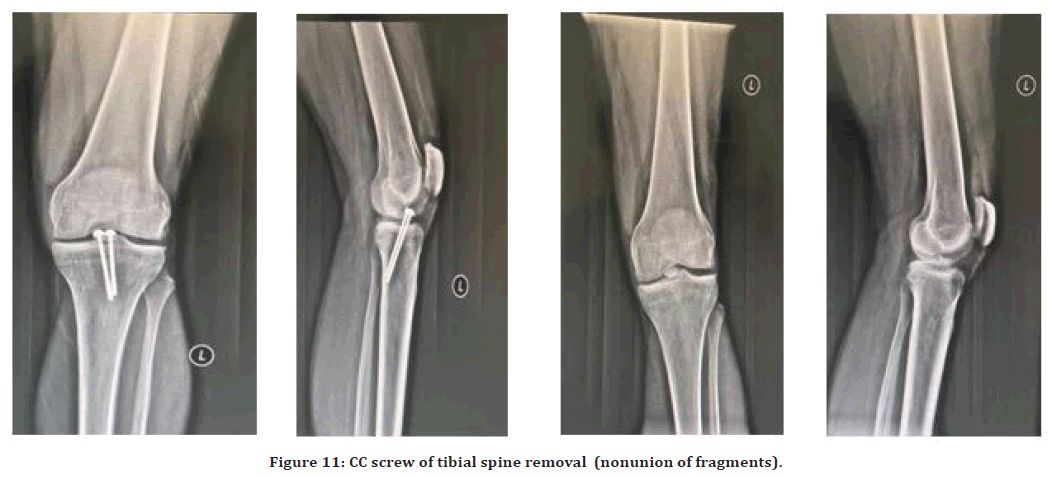

Post op complication

9 Chronic non healing ulcer in 3 cases.

9 Nonunion of fracture leading to redo fixation in 4 cases.

9 Re fracture at different site in post op period in 2 cases.

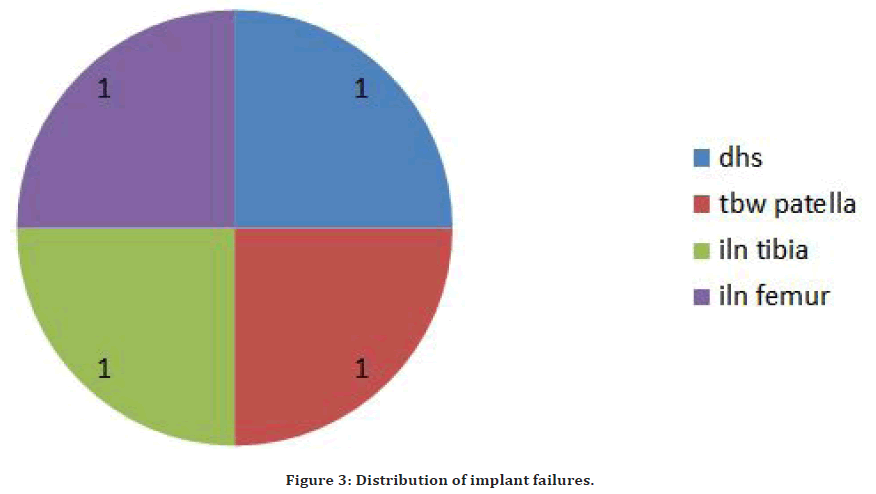

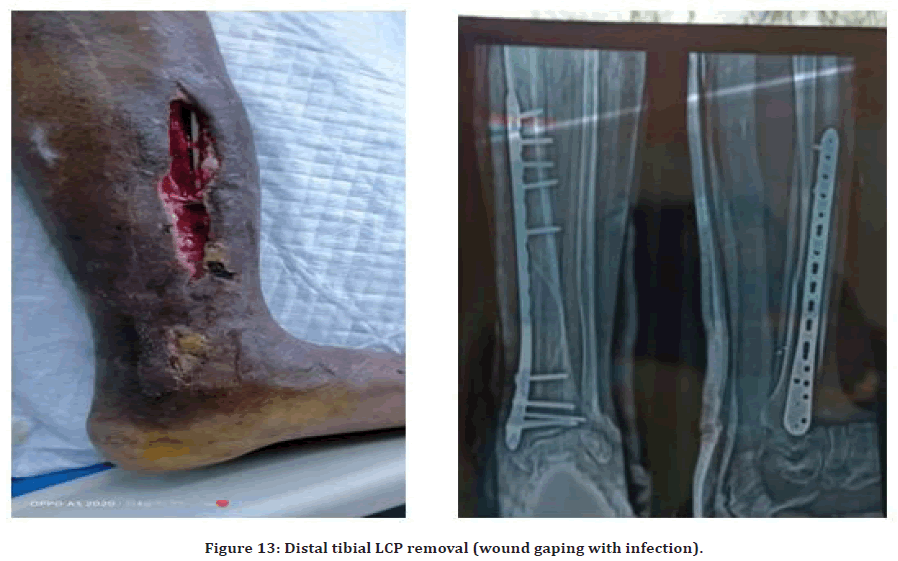

Diabetes and initial compound fracture wound managed definitively by internal fixation are most common comorbidities associated with removal surgeries (Figures 1-13).

Figure 1. Distribution of infective hardware.

Figure 2. Distribution of Paediatric hardware.

Figure 3. Distribution of implant failures.

Figure 4. Reasons for implant removal.

Figure 5. Types of implants removed.

Figure 6. Intra operative complications.

Figure 7. Post-operative complications.

Figure 8. TENS removal femur.

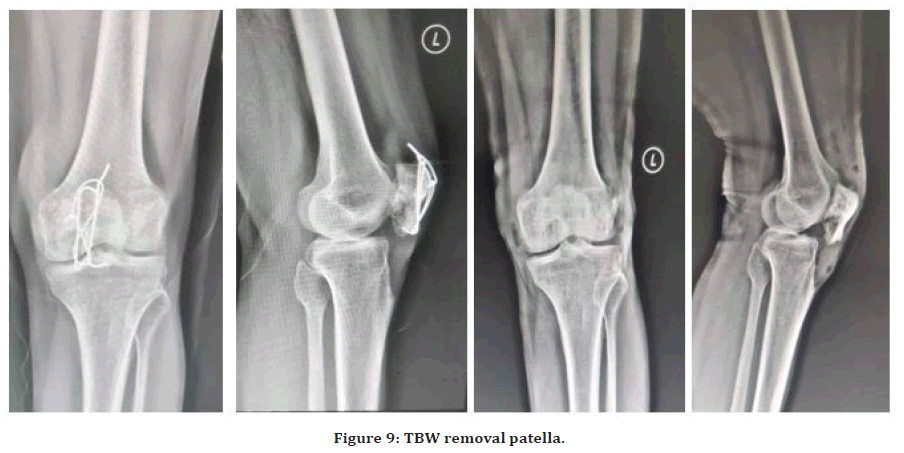

Figure 9. TBW removal patella.

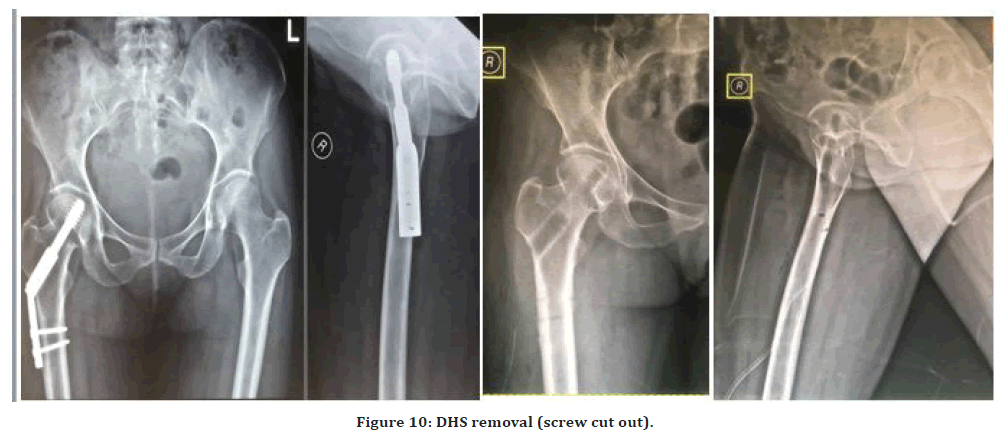

Figure 10. DHS removal (screw cut out).

Figure 11. CC screw of tibial spine removal (nonunion of fragments).

Figure 12. Bi malleolar removal (cellulitis of ankle).

Figure 13. Distal tibial LCP removal (wound gaping with infection).

Discussion

Metallic hardware inserted for fracture stabilization, may at some time or the other be removed for a variety of reasons. However there is still little consensus on if such hardware be removed routinely in the setting of a healed fractures [9]. Opinion and habits not only vary with surgeon-related factors (e.g., differences between countries), but also patient-related factors (e.g., differences between children and adults, anatomical locations) and implant-related factors (e.g., stainless steel versus titanium alloys) [7].

Paediatric group have different indications to be considered during clinical evaluation on follow up. Paediatric patients who have had internal fixation may have it removed if it causes pain, however it is advocated that such hardware especially in the hip be left alone. Distribution of aspects related to implant removal surely vary from cases to cases, and implications for doing surgeries should be weighted first, that how much benefit patient will get after operation.

Many a times, patient’s request becomes ‘absolute demand’ to get implant removed despite any ‘absolute indication’. Patient’s request may be phobia due metal inside body or fear related to future problems or advice from relatives/doctor. The social stigma may be because of this fear of implant in body cause infection in future.

Currently, most indications for removal are ‘relative’, meaning that they are not really necessary and are often driven by patient’s complaints and symptoms. Pain, functional impairment, prominent material, possible future problems, and the patient’s request are the main examples of ‘relative’ indications for removal [7]. These following indications can be considered as ‘absolute’ for hardware removal that includes Broken material, Infection, Avascular necrosis, Cut out of material, Intraarticular material, Tenosynovitis and Tendon rupture . Improvement of complaints after removal is debatable and disadvantages, such as surgery-related complications or even worsening of the complaints, can appear and are important reasons for the antagonists of removal to leave the implant in [10-13]. In general, the complication rate differs significantly between studies and estimated risks for adverse events vary from 0 to 1% for postoperative hematoma, up to 14% for wound infection, 1–29% for nerve injury, 1–30% for a refracture, and up to 9% for obtaining a cosmetically disturbing scar [10,11,13-19]. However, in symptomatic patients, the disadvantages are accepted to give these patients the benefit of the doubt, as one of the potential advantages of implant removal might be the improvement of complaints. On the other hand, in asymptomatic patients, it is accepted to leave the implant in.7 77% constituted male population came for their hardware removal. Our study, however, also included children with sum of 12.5%. Abidi et al reviewed 40 patients with implant-related pain who required removal. 30 of these (75%) were males [20].

Shrestha et al in their retrospective series also found a male preponderance (189 out of 275 patients) to the tune of 68.72% [21]. There categorically looks to be a strong male majority in implant removal surgeries. Male predominance might be because of their heavy labour work issue.

In our study, the most common reasons for removal are infective hardware(25%), patient demand(25%),prominent hardware(22%). Although we did not primarily aim to evaluate the outcome after removal, all our patients had at least some relief in their hardware pain at follow-up. There was a statistically significant improvement in the mean pain VAS after implant removal [22]. Brown et al found that 31% patients undergoing open reduction and internal fixation of ankle fractures had persistent lateral pain [23].

They also found that only 11 of 22 patients who got their hardware removed had improvement in the pain. Minkowitz et al prospectively studied 60 patients who had implant removal for hardware pain, and at 1 year follow-up all their patients were satisfied [2]. Implant failure (10%),peri implant fractures (5%) was the next most common indication in our series. Patient noncompliance, defective implants used, shortage of instrumentations, fault in technique, surgeons skill are the important consideration to be seen while performing surgeries. Akhtar et al cited the most common cause of failure as poor quality of the implant [24,25]. Peivandi et al also concluded that the most common reason for implant failure was poor manufacturing. They recommended that credible and trusted implant brands should be used in fracture fixation [26].

Sharma et al in a retrospective study of 41 failed upper and lower limb implants found that plate failure was more common than nail failure in the lower limb [27]. Hardware removal surgeries are mainly performed by post graduates and interns use to assist them followed by consultants in our institute as this is looked as straight forward or there is fewer struggles due to incision is taken over the old surgical scar and no obvious fear of likelihood of complication. Surgeons believe on his skills of performing the skilled operation but not the removal surgeries and this do not significantly contribute to operation duration (p>0.05).

Hospital stay also vary person to person for same kind of procedure and not significant (p>0.05). Khan et al corroborates our finding when they reported a hospital stay between 2-4 weeks as a result of infection.28 Matthew et al reported an overall average of 11 days of sick leave for IM nail removal in the lower limbs [9].

Refracture following removal of hardware was seen in 2 (5%) patient with in femurs because of porosis in our study. Refracture is most common in the forearm [10,14,16,17,28,29]. Refracture could result either before or after hardware removal. Refracture usually occurs from stress risers commonly associated with plates and screws, more especially with large fragment DCP system [29].

Conclusion

Implant removal is not needed in all cases .It should be done in selected cases where there is definitive indication such as Paediatric bones with open physics and infected implant.

Never do removals by patient force because most of the time we are failure to extract the implant and feel guilty. Always go with new implants and removal instruments set keeping in mind non unions and refracture. Implant removal is a by luck procedure for surgeons because sometimes it takes a day, eventhough it’s a failure. Superficially located implants are more commonly infected than deeper implants because of less muscle mass coverage.

References

- Hanson B, van der Werken C, Stengel D. Surgeons’ beliefs and perceptions about removal of orthopaedic implants. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008; 9:73.

- Busam ML, Esther RJ, Obremskey WT. Hardware removal: Indications and expectations. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006; 14:113–120.

- Loder RT, Feinberg JR. Orthopaedic implants in children: Survey results regarding routine removal by the pediatric and nonpediatric specialists. J Pediatr Orthop 2006; 26:510–519.

- Bo¨stman O, Pihlajamaki H. Routine implant removal after fracture surgery: A potentially reducible consumer of hospital resources in trauma units. J Trauma 1996; 41:846–849.

- Vos D, Hanson B, Verhofstad M. Implant removal of osteosynthesis: The Dutch practice. Results of a survey. J Trauma Manag Outcomes 2012; 6:1-7.

- Jamil W, Allami M, Choudhury MZ, et al. Do orthopaedic surgeons need a policy on the removal of metalwork? A descriptive national survey of practicing surgeons in the United Kingdom. Injury 2008; 39:362–367.

- Vos DI, Verhofstad MH. Indications for implant removal following fracture healing: A review of literature. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2013; 39:327-337.

- Schmittenbecher PP. Implant removal in children. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2013; 39:345-352.

- Matthew LB, Robert JE, William TO. Hardware removal: Indications and expectations. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006; 14:113-120.

- Sanderson PL, Ryan W, Turner PG. Complications of metalwork removal. Injury 1992; 23:29.

- Richards RH, Palmer JD, Clarke NM. Observations on removal of metal implants. Injury 1992; 23:25–28.

- Mu¨ller-Fa¨rber J. Metal removal after osteosyntheses. Indications and risks. Orthopade 2003; 32:1039–10357.

- Georgiadis GM. Percutaneous removal of buried antegrade femoral nails. J Orthop Trauma 2008; 22:52–55.

- Hidaka S, Gustilo RB. Refracture of bones of the forearm after plate removal. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984; 66:1241–1243.

- Deluca PA, Lindsey RW, Ruwe PA. Refracture of bones of the forearm after the removal of compression plates. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988; 70:1372–1376.

- Rumball K, Finnegan M. Refractures after forearm plate removal. J Orthop Trauma 1990; 4:124–129.

- Langkamer VG, Ackroyd CE. Removal of forearm plates. A review of the complications. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1990; 72:601–604.

- Rosson JW, Shearer JR. Refracture after the removal of plates from the forearm. An avoidable complication. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991; 73:415–417.

- Chia J, Soh CR, Wong HP, et al. Complications following metal removal: A follow-up of surgically treated forearm fractures. Singapore Med J 1996; 37:268.

- Abidi SA, Umer MF, Ashraf SM, et al. Outcome of painful implant removal after fracture union. Pak J Surg 2012; 28:114-117.

- Shrestha R, Shrestha D, Dhoju D, et al. Epidemiological and outcome analysis of orthopedic implants removal in Kathmandu University Hospital. Kathmandu Univ Med J 2013; 11:139-143.

- Haseeb M, Butt MF, Altaf T, et al. Indiations of implant removal: A study of 83 cases. Int J Health Sci 2017; 11:1–7.

- Brown OL, Dirschl DR, Obremskey WT. Incidence of hardware-related pain and its effect on functional outcomes after open reduction and internal fixation of ankle fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2001; 15:271-274.

- Minkowitz RB, Bhadsavle S, Walsh M, et al. Removal of painful orthopaedic implants after fracture union. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89:1906-1912.

- Akhtar A, Shami A, Abbassi SH, et al. Broken orthopaedic implants: An exerience at PIMS. Ann Pak Inst Med Sci 2009; 5:136-140.

- Peivandi MT, Yusof-Sani MR, Amel-Farzad H. Exploring the reasons for orthopedic implant failure in traumatic fractures of the lower limb. Arch Iran Med 2013; 16:478-82.

- Sharma AK, Kumar A, Joshi GR, et al. Retrospective study of implant failure in orthopaedic surgery. Med J Armed Forces India 2006; 62:70.

- Khan MS, Rehman S, Ali MA, et al. Infection in orthopedic implant surgery, Its risk factors and outcome. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2008; 20:23-25.

- Beaupré GS. Csongradi JJ. Refracture risk after plate removal in the forearm. J Orthop Trauma 1996; 10:87-92.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Author Info

Saini Thirupathi* and Gattu Naresh

Department of Orthopaedics, Prathima Medical College, Nagunoor, Karimnagar, Telangana, IndiaReceived: 06-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-61709; , Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-61709 (PQ); Editor assigned: 07-Jun-2022, Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-61709 (PQ); Reviewed: 21-Jun-2022, QC No. JRMDS-22-61709; Revised: 23-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-61709 (R); Published: 30-Jun-2022