Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 7

Factors Contributing to at Risk Marriages among Individuals with Hemoglobinopathy Disorders Attending Premarital Screening Centers in Al-Ahsa Governorate, Saudi Arabia- 2021-2022

Hajar Jawad Alsalem1*, Manahil Nouri2 and Rahma Baqer Alqadeeb3

*Correspondence: Hajar Jawad Alsalem, Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Email:

Abstract

Aim: Results from the Premarital Screening Program suggest that approximately 48% of couples with Hemoglobinopathy disorders decided to proceed with their marriage. This study determines the frequency of at-risk marriage among couples with Hemoglobinopathy disorders in Al Ahsa, Saudi Arabia and determines factors that influence their decision to proceed with at-risk marriage. Materials and Methods: Of the 182 couples identified, 116 (63.7%) married and 66 (36.3%) did not marry. An unmatched case-control study was conducted on 81 subjects who married (cases) and 44 subjects who did not marry (controls) to assess the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge, and cultural factors in regard to the decision to marry. Results: In the case-control study, a low education level was associated with a decreased risk to proceed with at-risk marriage (OR=0.16, p-value=0.03). “It is my fate and I have to accept it” was among the most reported factors that influenced individuals to proceed with at-risk marriage (15%). Fifty percent of those who did not proceed with at-risk marriage were convinced by the importance of having healthy children. Roughly 75% of the married group and 61% of the unmarried group were not aware of the aim of the Premarital Screening Program. Recommendations: raise the awareness of premarital screening program and to implement the screening at earlier stage. Counselor has to address different social, cultural and religious factors that may contribute to proceed with at-risk marriage. Conclusion: The study’s findings indicate that strong social, cultural, and religious factors lead to the reduced effectiveness of premarital counseling in the Al Ahsa region of the KSA.

Keywords

Premarital, Screening, At-risk marriage, Marriage, Factors

Methods

Study design, setting, and participants

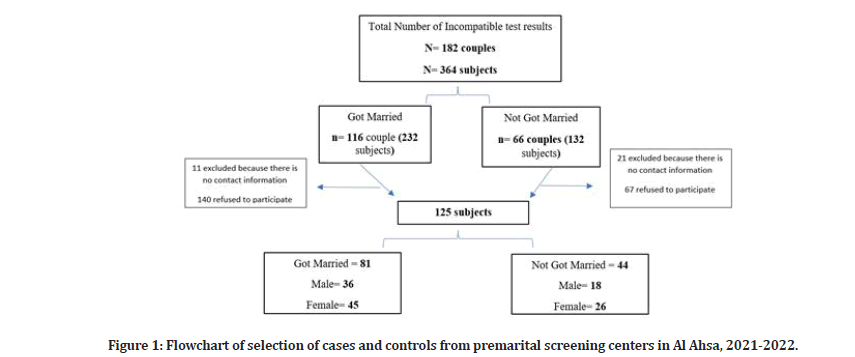

The current unmatched case-control study was conducted at the two premarital screening centers (i.e., Al Nuzha and Al Khaldyah) in Al Ahsa governorate, in the eastern region of the KSA from January 1, 2021 to May 31, 2022. During the study period, all subjects with incompatible screening results due to hemoglobinopathy were invited to participate (n=364), and subjects who gave consent were included in the study (Figure 1). The case group (232 subjects) was defined as participants with incompatible screening results due to hemoglobinopathy disorders who got married and were thus subjected to at-risk marriage. The control group (132 subjects) was defined as participants with incompatible screening results due to hemoglobinopathy disorders who did not marry and were thus not subjected to at-risk marriage.

Figure 1: Flowchart of selection of cases and controls from premarital screening centers in Al Ahsa, 2021-2022.

Data collection procedures and analysis

A self-administered questionnaire was developed in Arabic to collect the required data based on a literature review [21]. The research team and two experts reviewed the questionnaire for both face and content validity. The questionnaire was sent via Whatsapp to all subjects with incompatible screening test results, and it covered the following variables:

Socio-demographic and medical history data (i.e., age, gender, residency area, education level, monthly income, relationship to partner, marital status, and premarital screening test result).

Knowledge about the Premarital Screening Program and hemoglobinopathies (i.e., the aim of the program, how it affects children, available treatment for hemoglobinopathies, and whether they are curable diseases or not).

Cultural, familial, and religious factors that influence the decision to proceed with at-risk marriage.

Chi-square analyses were done for qualitative data, and logistic regression was conducted for the adjustment of possible confounders.

Ethical considerations

Each participant gave written informed consent prior to completing the questionnaire. The aim of the study was clearly stated for participants, and they were reassured about the confidentiality of their information.

Results

Of the 364 subjects identified from medical records as having incompatible test results, 32 subjects were excluded due to missing contact information. The questionnaire was sent to 332 subjects, of which 207 subjects refused to participate and 125 completed the questionnaire and were included in this study. Of the 125 individuals included in this study, 81 represented cases (i.e., who proceeded with at-risk marriage) and 44 represented controls (i.e., who did not proceed with atrisk marriage).

Demographic characteristics

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants. The majority of the married group (64.2%) are over 25 years old and 35.8% are under 25. Fifty percent of the unmarried group are under 25 and 50% are over 25. The participants’ age was statistically non-significant with the decision to proceed with at-risk marriage (OR=1.79). Females represent 55.6% of the married group and 59.1% of the unmarried group, while males represent 44.4% of the married group and 40.9% of the unmarried group. The majority of the married (67.9%) and unmarried groups (70.5%) live in the two cities of Al Ahsa, while 32.1% of the married group and 29.5% of the unmarried group live in Al Ahsa's villages. The participants who live in the two cities are less likely to proceed with at-risk marriage compared to participants living in the villages areas (OR=0.78).

| Case N=81 | Control N=44 | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | P- value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 36 (44.4%) | 18 (40.9%) | 1.16 (0.55-2.43) | ||

| Female | 45 (55.6%) | 26 (59.1%) | |||

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤ 25 | 29(35.8%) | 20(50%) | 1.79(0.85-3.78) | 1.2(0.51-2.79) | 0.68 |

| >25 | 52(64.2%) | 22(50%) | Reference | Reference | |

| Residency | |||||

| City | 55 (67.9%) | 31 (70.5%) | Reference | Reference | 0.62 |

| Village | 26 (32.1%) | 13 (29.5%) | 0.78 (0.4-1.97) | 1.24(0.53-2.86) | |

| Education Level | |||||

| Less than secondary | 13 (16%) | 2 (4.5%) | 0.19(0.04 – 0.95) | 0.16(0.03-0.87) | 0.03 |

| Secondary | 39 (48.1%) | 19 (43.2%) | 0.61(0.28 – 1.33) | 0.49(0.21-1.16) | 0.11 |

| Higher Education | 29 (35.8%) | 23 (52.3%) | Reference | Reference | |

| Job | |||||

| Governmental Sector | 11 (13.6%) | 5 (11.4%) | Reference | Reference | |

| Private Sector | 32 (39.5%) | 15 (34.1%) | 1.03 (0.30 – 3.50) | 2.78(0.75-10.32) | 0.13 |

| Student | 13 (16%) | 15 (34.1%) | 2.53(0.70-9.24) | 1.11(0.32-3.82) | 0.87 |

| Not Working | 25 (30.9%) | 9 (20.5%) | 0.79 (0.22 -2.91) | 0.81(0.22-3.02) | 0.76 |

| Monthly Income (SR) | |||||

| < 5,000 | 47 (58%) | 29 (65.9%) | 2.53(0.70-9.24) | 3.59(0.76-16.90) | 0.11 |

| 5.000 – 10,000 | 24 (29.6%) | 12 (27.3%) | 1.7(0.39 – 7.21) | 2.52(0.53-11.93) | 0.24 |

| > 10,000 | 10 (12.3%) | 3 (6.8%) | Reference | Reference | |

| Marital Status at Screening | |||||

| Never Married | 56 (69.1%) | 37 (74.4%) | 2.36 (0.93-6.01) | 2.25(0.82-6.21) | 0.12 |

| Second or more | 25 (30.9%) | 7 (15.9%) | Reference | Reference | |

| Relation with Partner | |||||

| Consanguineous | 34 (42%) | 13 (29.5%) | 0.58(0.27-1.27) | 0.45(0.19-1.05) | 0.07 |

| None | 47 (58%) | 31 (70.5%) | Reference | Reference | |

| *Adjusted for age, residency area, monthly income, education level, relation to partner, degree of marriage. | |||||

Table 1: Relationship of sociodemographic characteristics to marriage decision for at-risk individuals from premarital screening centers in Al Ahsa in 2021-2022.

Most of the married subjects (48.1%) had a secondary education, 35.8% had higher education, and 16% had less than secondary education. However, the majority (52.3%) of unmarried subjects had a higher education, 43.2% had secondary education, and 4.5% had less than secondary education. A statistically significant association exists between level of education and the decision to proceed with at-risk marriage. Those who had less than secondary education was less likely to proceed with at-risk marriage (OR=0.16, p-value=0.03).

Most married subjects (39.5%) were employed in the private sector, 30.9% were not employed, 16% were students, and 13.6% were employed in the governmental sector. By contrast, 34.1% of unmarried subjects were employed in the private sector, 34.1% were students, 20.5% were not employed, and 11.4% were employed in the governmental sector. Being employed in the private sector increased the risk of proceeding with at-risk marriage (OR=2.78) compared to governmental sector employees. Roughly 58% of married subjects and 65.9% of unmarried subjects are low income. Low-income participants were more likely to proceed with at-risk marriage than high-income participants (OR=3.59). It was the first marriage for 69% of married subjects and 74.4% of unmarried subjects, which tends to increase the likelihood of proceeding with at-risk marriage compared to participants who have been married before. The majority of the participants were not related to each other; in 58% of married subjects and 70.5% of unmarried subjects, consanguinity tended to decrease (OR=0.45, p-value=0.07) the risk of proceeding with at-risk marriage compared to participants who are not related to each other.

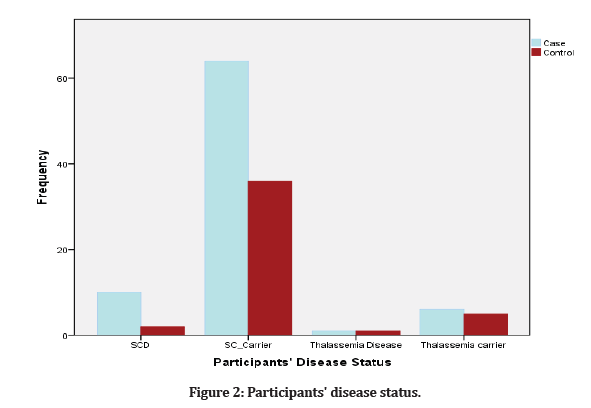

Disease status among participants

The majority of participants were SCD carriers: 87.7% and 86.4% in the married and the unmarried groups, respectively (Figure 2). Sickle cell disease was seen in 4.9% of married subjects and 4.5% of unmarried subjects, while 1.2% of married subjects and 2.3% of unmarried subjects were diagnosed with thalassemia. Thalassemia traits were evident in 6.2% of married subjects and 6.8% of unmarried subjects.

Figure 2: Participants' disease status.

Knowledge of premarital screening program

Participants were asked about the aim of the Premarital Screening Program, and 24.7% of the married group and 38.6% of the unmarried group knew the aim (Table 2). The majority of participants in the married group (89%) and in the unmarried group (95.5%) are aware that SCD and thalassemia are inherited blood disorders. Moreover, 91.4% of the married group and 88.6% of the unmarried group believed that SCD and thalassemia may affect their children’s health. The majority of participants in both the married (84%) and unmarried groups (86.4%) believe that SCD and thalassemia are curable diseases.

| Case N=81 | Control N=44 | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P- value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| The Aim of Premarital Screening | ||||

| Correct answer | 20(24.7%) | 17(38.6%) | 1.92 (0.87 -4.22) | 0.1 |

| Incorrect answer | 61(75.3%) | 27(61.4%) | ||

| Sickle Cell Disease and Thalassemia are Inherited Diseases | ||||

| Correct answer | 72(88.9%) | 42 (95.5%) | 2.63 (0.54-12.73) | 0.22 |

| Incorrect answer | 9 (11.1%) | 2 (4.5%) | ||

| Sickle Cell Disease and Thalassemia Can Affect Children's Health | ||||

| Correct answer | 74 (91.4) | 39 (88.6%) | 0.74 (0.22-2.48) | 0.62 |

| Incorrect answer | 7 (8.6%) | 5 (11.4%) | ||

| People Can Be Cured from Sickle Cell Disease and Thalassemia | ||||

| Correct answer | 13 (16%) | 6 (13.6%) | 0.83 (0.29-2.35) | 0.72 |

| Incorrect answer | 68 (84%) | 38 (86.4%) | ||

Table 2: Relationship of participants' knowledge and the decision of marriage for at-risk individuals from premarital screening centers in Al Ahsa in 2021-2022.

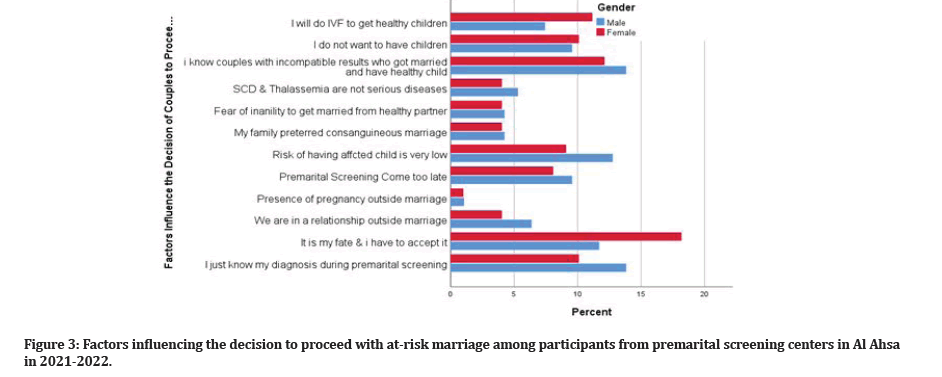

Reasons for proceeding with at-risk marriage

The 81 participants who decided to proceed with atrisk marriage were asked about the factors that affected their decision (Figure 3). They listed 12 reasons; in descending order of prevalence, they are as follows: (1) “it is my fate and I have to accept it” (n=29, 15%); (2) “I know couples with inherited blood diseases who have healthy children” (n=25, 13%); (3) “I just found out about my diagnosis when I took the premarital screening test” (n=23, 11.9%); (4) “I will have in-vitro fertilization” (n=22, 11.4%); (5) “the risk of having affected children is low” (n=21, 10.9%); (6) “I do not want to have children” (n=19, 9.8%); (7) “premarital screening occurred too late after the marriage decision had been made” (n=17, 8.8%); (8) “presence of relationship outside marriage” (n=10, 5.2%); (9) “SCD and thalassemia are not serious diseases” (n=9, 4.7%); (10) “my family preferred consanguineous marriage” (n=8, 4.1%); (11) “fear of inability to marry a healthy partner” (n=8, 4.1%); and (12) “presence of pregnancy outside marriage” (n=2, 1%).

Figure 3: Factors influencing the decision to proceed with at-risk marriage among participants from premarital screening centers in Al Ahsa in 2021-2022.

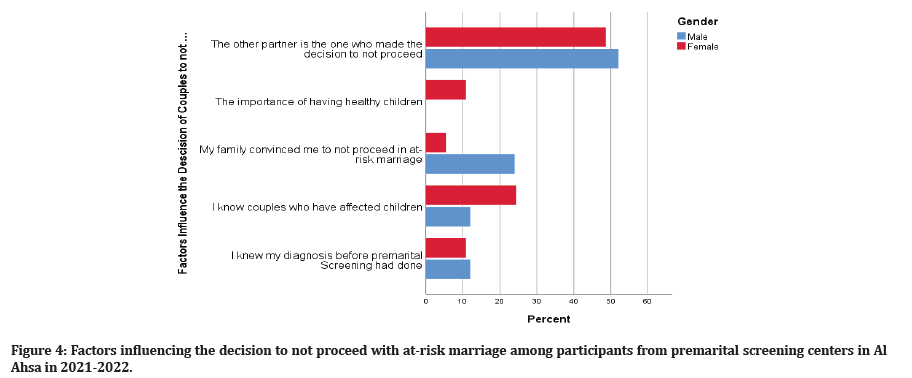

Reasons for not proceeding with at-risk marriage

The 44 participants who decided not to proceed in at-risk marriage were asked about the factors that influenced their decision (Figure 4). They listed five reasons; in descending order of prevalence, they are as follows: (1) “the importance of having healthy children” (n=31, 50%); (2) “I know couples who have children with SCD and thalassemia” (n=12, 19.4%); (3) “my family convinced me to not proceed with an at-risk marriage” (n=8, 12.9%); (4) “I knew my diagnosis before taking the premarital screening test” (n=7, 11.3%); and (5) “the other partner is the one who decided to not proceed” (n=4, 6.5%).

Figure 4: Factors influencing the decision to not proceed with at-risk marriage among participants from premarital screening centers in Al Ahsa in 2021-2022.

Logistic regression analysis

After adjustment for the confounders (i.e., age, residency area, income, education level, relation to partner, and degree of marriage), participants with less than secondary education are more likely not to proceed with at-risk marriage (OR=0.16, 95% CI=0.03–0.87, p-value=0.03).

Discussion

The KSA implemented the Premarital Screening Program in 2004. It is a mandatory test for all couples who intend to marry. Since couples with incompatible test results are not prohibited from proceeding with at-risk marriage, the efficacy of the program depends on the percentage of at-risk marriages averted [21]. The findings of this study convey that program success was not achieved, as approximately 63.7% of couples with incompatible test results due to hemoglobinopathies chose to proceed with at-risk marriage [22]. Alswaidi et al. reported that roughly 88% of at-risk couples proceeded with at-risk marriages in 2005–2006, and this figure decreased to 48% in 2009 [8,23,24].

Nationally, there has been a decrease in the prevalence rate of B-thalassemia, while the prevalence rate of SCD remains high [20]. The high prevalence of SCD is expected since couples often proceed with at-risk marriage. This finding emphasizes the presence of a knowledge gap in regard to the factors that influence a couple’s decision to proceed with at-risk marriage and how to improve counseling sessions to modify individuals’ behavior. This study discussed the possible factors that influence a couple’s decision.

Sociodemographic Factors influencing a couple’s decision

The Al Ahsa governorate is the largest part of the eastern region of the KSA. Hofuf et al. are its two main cities where the two premarital screening centers are located. There is wide variety of cultures and social composition across Al Ahsa [25]. This study showed that the majority of incompatible test results are due to the sickle cell trait, which is consistent with the prevalence pattern in the country [26].

There has been an increase in the average age of marriage in the KSA in recent years. Most marriages occur at age 26 [27]. In this study, the average age of marriage was 30 years, and it was the first marriage for the majority of participants. The high prevalence of hemoglobinopathies were linked to consanguineous marriage, which constitute 60% of marriages in the KSA, as the families believe that this type of marriage will strengthen their attachment [28]. In this study, consanguinity decreased the risk of proceeding with at-risk marriage. This finding is indirectly related to the influencing factors listed in this study.

In this study, no difference existed in the demographic characteristics between those who married and those who did not and thus no statistically significant association with proceeding with at-risk marriage, except for education level. Participants with lower than secondary education level were less likely to proceed with at-risk marriage than those with a higher education (OR=0.16, p-value=0.03).

Knowledge

The majority of participants were not aware of the aim of premarital screening, and most of participants believed that inherited hemoglobinopathies are curable diseases. Moreover, approximately 11% of participants who proceeded with at-risk marriage believed that the risk of having affected children is low, while others believed that SCD and thalassemia are not serious diseases [29,30]. While knowledge is an important factor, it is not sufficient to prevent at-risk marriage since many social, cultural, and religious factors influence the decision [14,24].

Factors influencing the decision

Participants who did not know their disease or carrier state prior to the premarital screening and participants did the screening after they had decided to marry are more likely to proceed with at-risk marriage. Because they are committed to their decision and had initiated wedding arrangements, cancellation of the wedding was not considered to be an option. Screening at an earlier stage and before marriage proposals may help to prevent at-risk marriage. This finding is consistent with Al Khalifah et al., in which 68% of participants supported early testing of hemoglobinopathies in high school and university students and before engagement [14].

In this study, participants who were married divorced, or had children at the time of screening were less likely to proceed with at-risk marriage. These are unexpected results, according to Alswaidi et al. [22]. Additionally, the Islamic culture in the KSA influenced the decision, as 15% of participants believed that this is their fate which they must accept. This emphasizes the importance of involving religious leaders in communities to participate in health education. The presence of new technologies such as in-vitro fertilization influenced some participants to proceed with at-risk marriage. These types of procedures are done for free in the KSA for special cases; otherwise, couples have to pay for them. In the study by Al Khalifah et al. approximately 34.5% preferred this alternative to ensure that their at-risk marriage would result in healthy children [14]. The findings of this study suggest that cultural and social factors may have a strong influence on the decision to proceed with at-risk marriage. This is consistent with Alswaidi et al. findings, in which fear of social stigma, inability to cancel a planned wedding, and familial pressure were among the most reported factors. This finding emphasizes the importance of considering cultural, social, and religious factors when counseling couples who have incompatible screening results.

Limitations

One limitation is the limited number of participants included in this study which affect the power.

Conclusion

The study’s findings indicate that strong social, cultural, and religious factors lead to the reduced effectiveness of premarital counseling in the Al Ahsa region of the KSA. The religious factor relates to the belief that at-risk marriage is one’s fate that they must accept. Another cultural factor is related to knowing couples who proceeded with at-risk marriage and yet had healthy children. Another factor is that the screening occurs late (i.e., individuals learn their disease status after taking the premarital screening test. This prevents the cancellation of a pre-planned wedding due to social commitments. These findings suggest a need to improve premarital counseling by considering cultural and religious factors. Furthermore, screening must occur at an earlier stage and before a marriage proposal to help prevent at-risk marriage.

Recommendations

Based on the study results, it is essential to raise awareness of inherited hemoglobinopathies as well as the Premarital Screening Program among individuals in the community. This will be achieved by including the students in the education programs and encouraging the religious leaders in each community to participate in increasing awareness among individuals. Moreover, offering premarital screening services at an earlier stage prior to a marriage proposal would help each partner to be aware of their diagnosis earlier and to make an informed decision. Considering the social and cultural factors in each counseling session is key to preventing at-risk marriage.

References

- https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/documents/nbs_hemoglobinopathy-testing_122015.pdf

- Modell B, Darlison M. Global epidemiology of haemoglobin disorders and derived service indicators. Bulletin World Health Organization 2008; 86:480-487.

- Sahu P, Purohit P, Mantri S, et al. Spectrum of hemoglobin disorders in southern Odisha, India: A hospital based study. Porto Biomed J 2021; 6.

- AlHamdan NAR, AlMazrou YY, AlSwaidi FM, et al. Premarital screening for thalassemia and sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabia. Genet Med 2007; 9:372–377.

- Alhosain A. Premarital screening programs in the Middle East, from a human right’s perspective. Diversity Equality Health Care 2018; 15.

- Alsaeed ES, Farhat GN, Assiri AM, et al. Distribution of hemoglobinopathy disorders in Saudi Arabia based on data from the premarital screening and genetic counseling program, 2011–2015. J Epidemiol Global Health 2018; 7:S41-7.

- Al-Rahal NK. Inherited bleeding disorders in iraq and consanguineous marriage. Int J Hematol Stem Cell Res 2018; 12:272–280.

- Alswaidi FM, O'brien SJ. Premarital screening programmes for haemoglobinopathies, HIV and hepatitis viruses: Review and factors affecting their success. J Med Screen 2009; 16:22-28.

- Hamamy HA, Al-Allawi NA. Epidemiological profile of common haemoglobinopathies in Arab countries. J Community Genet 2013; 4:147-167.

- Lee YK, Kim HJ, Lee K, et al. Recent progress in laboratory diagnosis of thalassemia and hemoglobinopathy: A study by the Korean red blood cell disorder working party of the Korean society of hematology. Blood Res 2019; 54:17–22.

- Manuscript A. NIH Public Access. 2014; 60:1363–1381.

- Gesteira EC, Bousso RS, Misko MD, et al. Families of children with sickle cell disease: An integrative review. Online Br J Nurs 2016; 15:276-290.

- Walters MC, Patience M, Leisenring W, et al. Bone marrow transplantation for sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:369–376. Google Scholar

- Alkhalifah AA, Al shakhs AA, AlQuwaidhi AJ. Knowledge and attitudes toward the premarital screening programme and its results among the service utilizers in Al-Hassa. Int J Curr Med Pharm Res 2018; 4:3706-3712.

- Makkawi M, Alasmari S, Hawan AA, et al. An update on the prevalence trends in Southern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2021; 42:784-789. Google Scholar

- Alhowiti A, Shaqran T. Premarital screening program knowledge and attitude among Saudi University Students in Tabuk City 2019. Int J Med Res Heal Sci 2019; 8:75–84.

- Gosadi IM. National screening programs in Saudi Arabia: overview, outcomes, and effectiveness. J Infect Public Health 2019; 12:608-614.

- Al-Shroby WA, Sulimani SM, Alhurishi SA, et al. Awareness of premarital screening and genetic counseling among Saudis and its association with sociodemographic factors: A national study. J Multidiscip Healthc 2021; 14:389.

- https://www.moh.gov.sa/Ministry/About/Health%20Policies/004.pdf

- Chaker L, Falla A, van der Lee SJ, et al. The global impact of non-communicable diseases on macro-economic productivity: A systematic review. Eur J Epidemiol 2015; 30:357–395.

- https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/About/Health%20Policies/005.pdf

- Alswaidi FM, Memish ZA, O'brien SJ, et al. At‐risk marriages after compulsory premarital testing and counseling for β‐thalassemia and sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabia, 2005–2006. J Gen Counsel 2012; 21:243-255.

- Jastaniah W. Epidemiology of sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med 2011; 31:289-293.

- Gosadi IM, Gohal GA, Dalak AE, et al. Assessment of factors associated with the effectiveness of premarital screening for hemoglobinopathies in the South of Saudi Arabia. Int J Gen Med 2021; 14:3079.

- Salehi F, Ahmadian L, Ansari R, et al. The role of information resources used by diabetic patients on the management of their disease. Med J Mashhad Univ Med Sci 2016; 59:17-25.

- Memish ZA, Owaidah TM, Saeedi MY. Marked regional variations in the prevalence of sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia in Saudi Arabia: Findings from the premarital screening and genetic counseling program. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2011; 1:61–68.

- http://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/ar-demographic-research-016_0.pdf%0Ahttps://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/en-dmaps2010_0_0.pdf%0Ahttp://www.academia.edu/download/37073061/GIS_5th_metwaly.pdf%0Ahttp://www.cdsi.gov.sa/english/index.php?o

- Heidari F, Dastgiri S, Akbari R, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of consanguineous marriage. Electron J Gen Med 2015; 11:248–255.

- Algahtani H, Almarri AK, Alharbi JH, et al. Multiple sclerosis in Saudi Arabia: Clinical, social, and psychological aspects of the disease. Cureus 2021; 13.

- Al-Aama JY, Al-Nabulsi BK, Alyousef MA, et al. Knowledge regarding the national premarital screening program among university students in western Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2008; 29:1649–1653.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Author Info

Hajar Jawad Alsalem1*, Manahil Nouri2 and Rahma Baqer Alqadeeb3

1Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia2Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Alneelain University, Khartoum, Sudan

3Community Medicine Specialist-Joint Program of Preventive Medicine, Al Ahsa Health cluster, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Received: 08-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-68989; , Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-68989 (PQ); Editor assigned: 10-Jun-2022, Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-68989 (PQ); Reviewed: 24-Jun-2022, QC No. JRMDS-22-68989; Revised: 29-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-68989 (R); Published: 06-Jul-2022