Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 2

Association between Mouth Breathing Habit and Dental Caries-A Retrospective Study

*Correspondence: Sowmya K, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences Saveetha University, India, Email:

Abstract

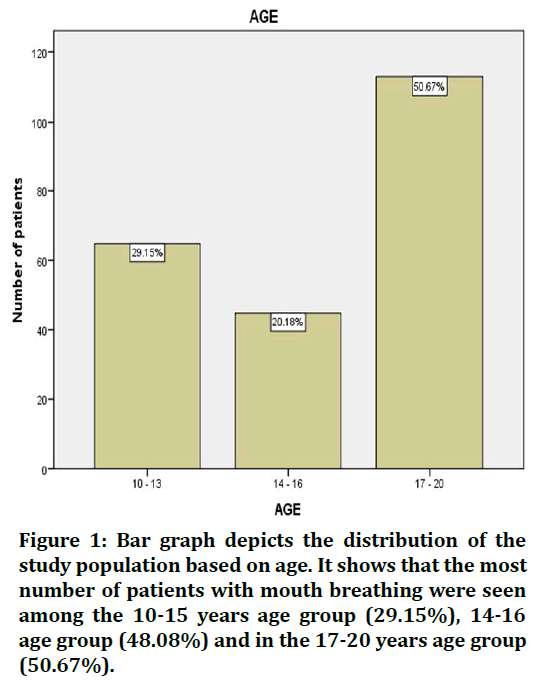

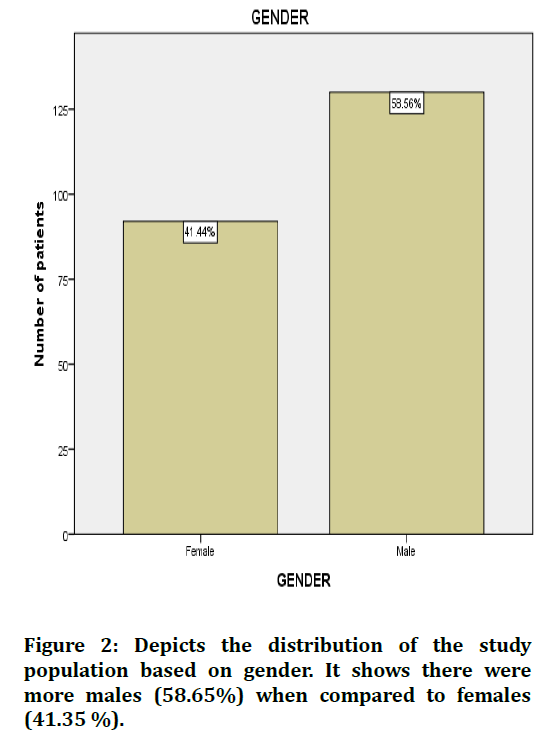

Introduction: Mouth breathing is an unnatural act of necessity to get air into the lungs through the mouth when the primary airway is blocked by nasal, nasopharyngeal such as enlarged adenoids, enlarged tonsils, rhinitis, nasal septal deviation, sinusitis, turbinate hypertrophy and nasal polyp. During mouth breathing, there is loss of saliva and dryness of the mouth and this can increase the risk of tooth decay and inflammation of the gingiva. Aim of the study: The aim of the present study was to find an association between mouth breathing and the presence of dental caries. Methodology: A retrospective analysis of all the cases with mouth breathing and their dental caries history among out-patients was retrieved among the overall data of patients visiting Saveetha Dental College from June 2020-March 2021. The data for 1206 patients of age group 10-20 years was collected and entered in excel spread sheets. And the collected data was analysed using SPSS software version 21.0. Chi square test was used to statistically evaluate the results. The level of significance was set at P<0.05. Results: In this study, the patients seen in the 10-15 years age group were (29.15%), (20.18%) in the age group of 14-16 years and 50.67% in the 17-20 age group. There was more number of male patients (58.65%) than female patients (41.35 %). When presence of dental caries and mouth breathing habit was analysed, Chi square test was found to be not significant (P>0.05). Conclusion: Within the limits of this study, no significant association was found between dental caries experience and mouth breathing. Although the relationship between mouth breathing and medical conditions and certain oral conditions seems to be well established, it is difficult to assess in all cases from the literature data, the exact link between the caries experience and mouth breathing. So, more studies are needed to explore a causal relationship since many studies have failed to find associations between mouth breathing and caries risk or salivary patterns.

Keywords

Age, Caries, Gender, Novel technique, Mouth breathing

Introduction

Oral habits are learned patterns of muscular contraction. Abnormal habits such as finger sucking, lip sucking, tongue thrusting, abnormal muscle habit can interfere with regular patterns of facial growth [1,2]. But psychologists believe that these habits can become "Bad Oral Habits", if continued longer than normal may cause physical damage to social or cognitive development [3,4]. Mouth breathing refers to the state of inhaling and exhaling through the mouth. The literature describes the prevalence of mouth breathing as ranging from 5 to 75% of tested children [5]. Excessive mouth breathing is problematic because of different disturbances. The air is not filtered and warmed as much as when inhaled through the nose, as it bypasses the nasal canal and Paranasal sinuses, and dries out the mouth, among other mechanisms. Mouth breathing is often associated with congestion, obstruction, or other abnormalities of the upper respiratory tract as well as other oral and medical conditions.

Dental caries is described as a multifactorial disease, in which the anatomy of the oral cavity, strength of the dental tissue, salivary composition, crevicular fluid, and diet are as important as the formation of bacterial plaque and the microorganisms that cause the disease. Since 1970, there has been a considerable reduction in the prevalence of dental caries in the majority of developed countries [6]. While a number of authors report improvements in oral health status in recent decades [7,8].

Saliva has many important functions. Among them are self-cleaning of the mouth, buffering and clearing acids, acquired pellicle formation, antimicrobial actions, and provision of ions for remineralization of demineralized enamel.

It protects the teeth from organic acids produced by bacteria which cause dental caries, and the extrinsic and intrinsic acids that initiate dental erosion. The depressed resting salivary flow is associated with lower plaque pH, increased numbers of lactobacilli and candida species, and greater caries risk.

This could have serious consequences for caries activity, and will also increase the risk of tooth loss via dental erosion [9]. When the subject breathes through the mouth, there is loss of saliva and dryness of the mouth and this can increase the risk of tooth decay and inflammation of the gingiva.

As mouth breathing causes water loss it is a potential factor which could contribute to oral dryness. Some studies have failed to find associations between mouth breathing and caries risk or salivary patterns.

The aim of the study is to find the association between mouth breathing and dental caries experience. Our team has extensive knowledge and research experience that has translated into high quality publications [10-29].

Materials and Methods

Study design: Retrospective study.

Study population: A retrospective study was carried out among young adults reporting to Saveetha Dental College and Hospital. The study was conducted between June 2020-March 2021. The study population consisted of patients who reported mouth breathing habit.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee and Scientific Review Board [SRB] of Saveetha Dental College.

Data collection: The data were collected by analyzing the records of 86,000 patients between June 2020-March 2021. The data included the patient's demographic details, history of mouth breathing and caries status.

Data analysis: The collected data were entered in an Excel sheet and subjected to statistical analysis using SPSS software. Bar charts were made on the number of caries for the tooth number 11, 21 and 31.

Results

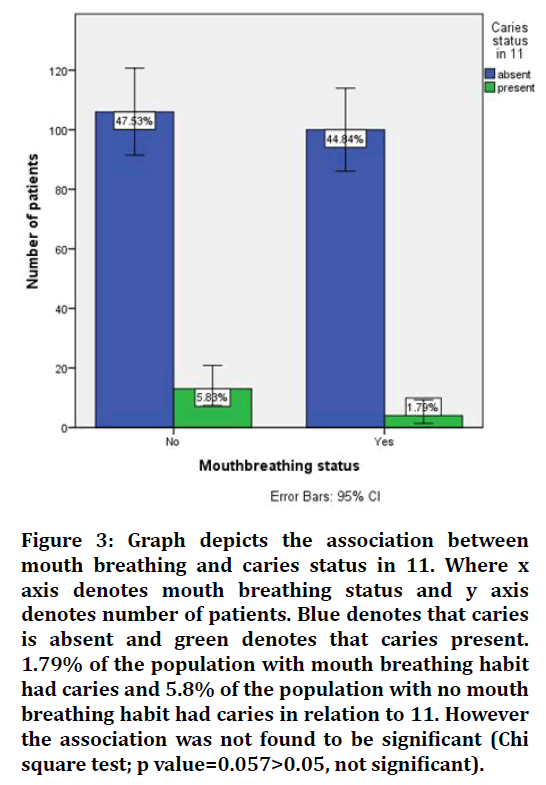

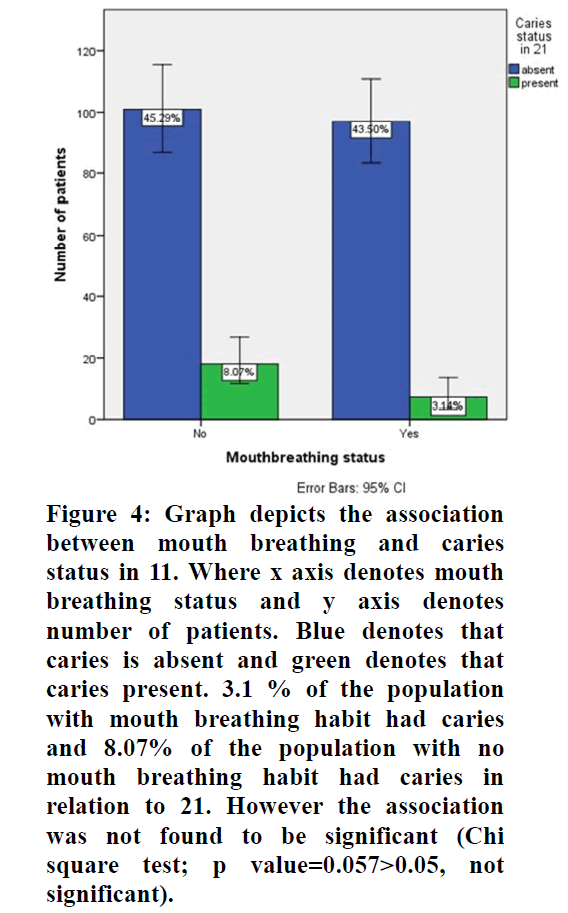

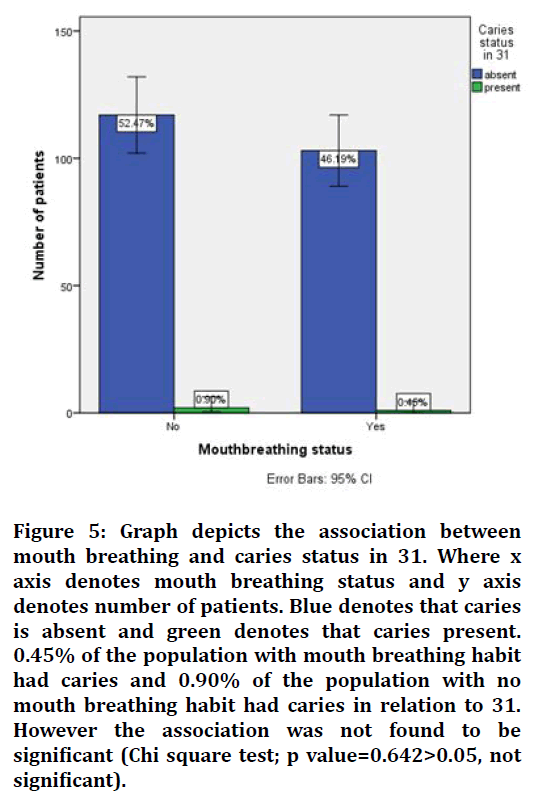

In this study the patients seen in the 10-15 years age group were (29.15%), (20.18%) in the age group of 14-16 years and 50.67% in the 17-20 age group (Figure 1) and this study showed there were more number of male patients (58.65%) reported having mouth breathing when compared to female patients (41.35 %) (Figure 2). The association of mouth breathing and dental caries has been presented in Figures 3 to Figure 5.

Figure 1. Bar graph depicts the distribution of the study population based on age. It shows that the most number of patients with mouth breathing were seen among the 10-15 years age group (29.15%), 14-16 age group (48.08%) and in the 17-20 years age group (50.67%).

Figure 2. Depicts the distribution of the study population based on gender. It shows there were more males (58.65%) when compared to females (41.35 %).

Figure 3. Graph depicts the association between mouth breathing and caries status in 11. Where x axis denotes mouth breathing status and y axis denotes number of patients. Blue denotes that caries is absent and green denotes that caries present. 1.79% of the population with mouth breathing habit had caries and 5.8% of the population with no mouth breathing habit had caries in relation to 11. However the association was not found to be significant (Chi square test; p value=0.057>0.05, not significant).

Figure 4. Graph depicts the association between mouth breathing and caries status in 11. Where x axis denotes mouth breathing status and y axis denotes number of patients. Blue denotes that caries is absent and green denotes that caries present. 3.1 % of the population with mouth breathing habit had caries and 8.07% of the population with no mouth breathing habit had caries in relation to 21. However the association was not found to be significant (Chi square test; p value=0.057>0.05, not significant).

Figure 5. Graph depicts the association between mouth breathing and caries status in 31. Where x axis denotes mouth breathing status and y axis denotes number of patients. Blue denotes that caries is absent and green denotes that caries present. 0.45% of the population with mouth breathing habit had caries and 0.90% of the population with no mouth breathing habit had caries in relation to 31. However the association was not found to be significant (Chi square test; p value=0.642>0.05, not significant).

Discussion

In this study the age group taken was 10-15 years age group (51.92%) and (48.08%) in the 16-20 years age group. There were more number of male patients (58.65%) reported having mouth breathing when compared to female patients (41.35 %). The tooth number taken to assess the caries was 21, 11 and 31 and the caries status. However, Al-Awadi et al. found lower salivary flow rate among male patients 18-22 years old with mouth breathing associated with nasal obstruction in comparison to nose breathers. Mouth breathing was also associated with lower salivary pH, higher plaque index and increased salivary mutans streptococci counts. Other studies also report association between mouth breathing and dental caries [30,33].

In our study caries status were given to the mouth breathing patients for 11 (tooth number). 44.84% of the people with mouth breathing habit had caries and 47.53% of the patients without mouth breathing had caries present in relation to 11. The results were found to be not significant and hence proving no significant relationship between mouth breathing and dental caries. Similar results was found in a study by Koga-Ito et al. [30] found no differences in caries risk between treated and untreated children for mouth breathing syndrome, although the level of IgG antibodies to S. mutans (cariogenic bacteria) was higher in the treated group. Another study did not find differences in flow rates or buffering capacities of resting and stimulated saliva between mouth- or nose-breathers adolescents aged 10-19 years.

The results of this study should be considered in highlighting its limitations. As this was a nonrepresentative descriptive study of the mouth-breathers only, the results could not be generalized for the whole population. The factors like family income and level of parental education that could be associated with a child's oral health practice were not assessed in this study.

It also remains uncertain whether mouth breathing has a causal relationship with gingival inflammation or dental caries. Prospective cohort studies including both mouth breather children and children without mouth breathing strongly suggested to fully clarifying the mechanism between mouth breathing and oral health by performing multivariate analyses like logistic regression.

Limitations

The main of this study is limited sample size and confined to a single source for data. Further descriptive studies on a larger scale can help us to give comprehensive data for arriving at a conclusion and to plan health oral health programs for the population studied.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of the current study, The effect of mouth breathing on the oral cavity remains controversial, and research about this topic is scarce. This study investigated the effect of mouth breathing on the levels of dental caries and it was found that there was no significant relation. However further studies are recommended on this topic after examining the individuals while possibly assessing more segments of the mouth to give an overview of the general dental to find an association as these were the main limitations in this study.

Acknowledgement

The authors sincerely acknowledge the faculty Medical record department and Information technology department of SIMATS for their tireless help in sorting out datas pertinent to this study.

Authors Contribution

Ushanthika T: Literature search, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing.

Dr. Sowmya K: Study design, data verification, manuscript drafting.

Funding

The authors declare that the present project is funded by Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha Dental college and hospitals, Saveetha university.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there were no conflicts of interest in the present study.

References

- Mathewson RJ, Primosch RE. Fundamentals of pediatric dentistry. 1995. 400 p.

- Hazzard FW. A thumb sucking cure. Child Dev 1932; 3:80.

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780323287456/mcdonald-and-averys-dentistry-for-the-child-and-adolescent

- Nowak AJ, Warren JJ. Infant oral health and oral habits. Pediatr Clin North Am 2000; 47:1043-66.

- Bonuck KA, Chervin RD, Cole TJ, et al. Prevalence and persistence of sleep disordered breathing symptoms in young children: A 6-year population-based cohort study. Sleep 2011; 34:875–84.

- Pieper K, Schulte AG. The decline in dental caries among 12-year-old children in Germany between 1994 and 2000. Community Dent Health 2004; 21:199–206.

- Larmas M. Has dental caries prevalence some connection with caries index values in adults? Caries Res 2010; 44:81–84.

- Silver DH. Trends in dental caries prevalence in english children: A socio-dental study. (Doctoral dissertation) 1985; 486.

- Scully C, Felix DH. Oral medicine-update for the dental practitioner: Dry mouth and disorders of salivation. Br Dent J 2005; 199:423–427.

- Muthukrishnan L. Imminent antimicrobial bioink deploying cellulose, alginate, EPS and synthetic polymers for 3D bioprinting of tissue constructs. Carbohydr Polym 2021; 260:117774.

- PradeepKumar AR, Shemesh H, Nivedhitha MS, et al. Diagnosis of vertical root fractures by cone-beam computed tomography in root-filled teeth with confirmation by direct visualization: A Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod 2021; 47:1198–214.

- Chakraborty T, Jamal RF, Battineni G, et al. A review of prolonged post-COVID-19 symptoms and their implications on dental management. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18.

- Muthukrishnan L. Nanotechnology for cleaner leather production: A review. Environ Chem Lett 2021; 19:2527–2249.

- Teja KV, Ramesh S. Is a filled lateral canal-A sign of superiority? J Dent Sci 2020; 15:562.

- Narendran K, Sarvanan A. Synthesis, characterization, free radical scavenging and cytotoxic activities of phenylvilangin, a substituted dimer of embelin. Indian J Pharm Sci 2020; 82:909-912.

- Reddy P, Krithikadatta J, Srinivasan V, et al. Dental caries profile and associated risk factors among adolescent school children in an Urban South-Indian City. Oral Health Prev Dent 2020; 18:379–386.

- Sawant K, Pawar AM, Banga KS, et al. Dentinal microcracks after root canal instrumentation using instruments manufactured with different NiTi alloys and the SAF system: A systematic review. Adv Sci Inst Ser E Appl Sci 2021; 11:4984.

- Bhavikatti SK, Karobari MI, Zainuddin SLA, et al. Investigating the antioxidant and cytocompatibility of mimusops elengi linn extract over human gingival fibroblast cells. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18.

- Karobari MI, Basheer SN, Sayed FR, et al. An In vitro stereomicroscopic evaluation of bioactivity between Neo MTA plus, pro root MTA, biodentine & glass ionomer cement using dye penetration method. Materials 2021; 14.

- Rohit Singh T, Ezhilarasan D. Ethanolic extract of Lagerstroemia speciosa [L.] Pers., induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in HepG2 cells. Nutr Cancer 2020; 72:146–156.

- Ezhilarasan D. MicroRNA interplay between hepatic stellate cell quiescence and activation. Eur J Pharmacol 2020; 885:173507.

- Romera A, Peredpaya S, Shparyk Y, et al. Bevacizumab biosimilar BEVZ92 versus reference bevacizumab in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 3:845–855.

- Raj RK. β-Sitosterol-assisted silver nanoparticles activates Nrf2 and triggers mitochondrial apoptosis via oxidative stress in human hepatocellular cancer cell line. J Biomed Mater Res 2020; 108:1899–1908.

- Vijayashree Priyadharsini J. In silico validation of the non-antibiotic drugs acetaminophen and ibuprofen as antibacterial agents against red complex pathogens. J Periodontol 2019; 90:1441–1448.

- Priyadharsini JV, Vijayashree Priyadharsini J, Smiline Girija AS, et al. In silico analysis of virulence genes in an emerging dental pathogen A. baumannii and related species. Arch Oral Biol 2018; 93–98.

- Uma Maheswari TN, Nivedhitha MS, Ramani P. Expression profile of salivary micro RNA-21 and 31 in oral potentially malignant disorders. Braz Oral Res 2020; 34:e002.

- Gudipaneni RK, Alam MK, Patil SR, et al. Measurement of the maximum occlusal bite force and its relation to the caries spectrum of first permanent molars in early permanent dentition. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2020; 44:423–428.

- Chaturvedula BB, Muthukrishnan A, Bhuvaraghan A, et al. Dens invaginatus: A review and orthodontic implications. Br Dent J 2021; 230:345–350.

- Kanniah P, Radhamani J, Chelliah P, et al. Green synthesis of multifaceted silver nanoparticles using the flower extract of Aerva lanata and evaluation of its biological and environmental applications. Chem Select 2020; 5:2322–31.

- Koga-Ito CY, Unterkircher CS, Watanabe H, et al. Caries risk tests and salivary levels of immunoglobulins to Streptococcus mutans and Candida albicans in mouthbreathing syndrome patients. Caries Res 2003; 37:38–43.

- Al-Awadi RN, Al-Casey M. Oral health status, salivary physical properties and salivary mutans streptococci among a group of mouth breathing patients in comparison to nose. J Baghdad College Dent 2013; 25:152–159.

- Wu L, Chang R, Mu Y, et al. Association between obesity and dental caries in Chinese children. Caries Res 2013; 47:171–176.

- Schenkel AB. Can promoting breastfeeding for new mothers prevent early childhood caries?. Cochrane Clin Answers 2020.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Author Info

Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences Saveetha University, Chennai, IndiaReceived: 10-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-46858; , Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-46858 (PQ); Editor assigned: 12-Jan-2022, Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-46858 (PQ); Reviewed: 26-Jan-2022, QC No. JRMDS-22-46858; Revised: 31-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-46858 (R); Published: 27-Feb-2022