Research Article - (2023) Volume 11, Issue 6

Anti-inflammatory effect of Rhamnus prinoides mouthwash in relation to Gingival Crevicular Fluid volume and IL-1β in a group of orthodontic patients (In Vivo study)

Karrar N Al-Mujamaii* and Athraa M Al Waheb

*Correspondence: Karrar N Al-Mujamaii, Department of Pedodontic and Preventive Dentistry, College of Dentistry, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq, Email:

Abstract

Background: Medicinal plants are recognized for their capacity to produce a wealth of bioactive compounds and mankind has used many species for centuries to treat a variety of diseases. Rhamnus prinoides is one of the medicinal plants that have been used traditionally for the treatment of different infectious diseases. It has different ethno medicinal uses in different countries; different parts of plant are used in the management of ear, nose and throat infections, gonorrhea, malaria and brucellosis.

Materials and methods: Rhamnus prinoides mouthwash was extracted from plant leaves, filtered and then it was mixed with ethanol after being dried. The anti-inflammatory effect was evaluated by measuring the gingival crevicular fluid volume and the concentration of Interleukine-1β (IL-1β) before and after 3 weeks of using Rhamnus prinoides mouthwash and placebo in study and control group respectively.

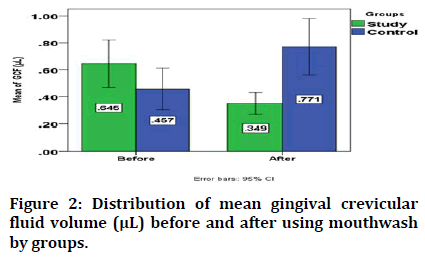

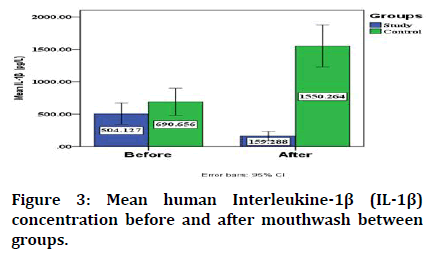

Results: Rhamnus prinoides mouthwash revealed anti-inflammatory effect by significantly reducing the mean gingival crevicular fluid volume from 0.645 ± 0.378 μL to 0.349 ± 0.173, additionally it significantly reduced the mean IL-1β concentration from 504.127 ± 353.105 pg/L to 159.288 ± 150.726 pg/L after 3 weeks of using Rhamnus prinoides mouthwash in study group. While in control group the mean gingival crevicular fluid volume significantly increased from 0.457 ± 0.329 μL to 0.771 ± 0.450 μL and the mean concentration of IL-1β significantly increased from 690.656 ± 450.494 pg/L to 1550.264 ± 693.167 pg/L after 3 weeks of using placebo.

Conclusion: Rhamnus prinoides leaf extract demonstrated a significant anti-inflammatory activity by improving the gingival condition from moderate type of gingival inflammation to mild type, and thus it can be considered as a promising oral health care product in the future.

Keywords

Rhamnus prinoides mouthwash, Anti-inflammatory effect, Gingival crevicular fluid, Interleukine-1β

Introduction

A variety of plant materials leaves, stems, roots, barks, fruits, seeds, flowers and so on are used for preparation of herbal medicines. They may contain various biologically active ingredients and are used primarily for the treatment of mild to chronic ailments. Numerous plants may contain polyphenols, alkaloids and volatile oils as active constituents that are utilized as popular folk medicines, whereas others gained popularity in the form of phytomedicines [1].

Regarding periodontal status, because of limited usefulness of traditional clinical measurements (they are indicators of previous periodontal disease rather than present disease activity), there is a need for development of new diagnostic tests that can detect not only the presence of active disease, but also predict future disease progression and evaluate the response to periodontal therapy, thereby improving the clinical management of periodontal patients, so advances in oral and periodontal disease diagnostic researches are moving toward methods whereby periodontal risk can be identified and quantified by objective measures such as biomarkers [2]. Gingival crevicular fluid can be used as a source of these biomarkers which are associated with changes and destruction in the underlying periodontium [3].

Medicinal plants are screened as a potential source of antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agents because increased resistance of biofilm pathogens to antibiotics as well as the side effects of these therapies. Rhamnus prinoides as one of these medicinal plants was used traditionally for treating different infectious diseases [4]. Its alkaloid and glycoside content are responsible for its antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity respectively [5,6].

Materials and Methods

The plant collection and authentication, cytotoxic effect, as well as minimum inhibitory and minimum bactericidal concentrations were mentioned in previous study [7].

The sample

This study was done to assess anti-inflammatory activity of RP leaf extract that will be extracted from the plant leaves with the aid of soxhlet apparatus. The study included 40 patients with moderate gingivitis, those patients were randomly allocated to either study or control group to ensure accessibility and isolation [8]. The anti-inflammatory activity was assessed by evaluating the gingival crevicular fluid volume and mean Interleukine-1β (IL-1β ) concentration for those patients before and after 3 weeks of using Rhamnus prinoides mouthwash and placebo (flavored distilled water) by study (20 patients) and control (20 patients) groups respectively after instructing them to wash their mouth 2 times daily.

The sampling of gingival crevicular fluid was done in the morning 2-3 hours after breakfast from the distal surfaces of 6 maxillary anterior teeth (right and left central incisors, lateral incisors, and canines). To avoid salivary, blood, and plaque contamination of sample the sites from which the fluid was taken were isolated with a cotton roll and the supra gingival plaque was removed with a curette.

According to Brills technique of crevicular fluid sampling, the periopaper strips were inserted into the gingival sulcus to about 1 mm until slight resistance was felt and left in place for 30 seconds to obtain the crevicular fluid sample [9,10]. Then after removal from the gingival sulcus each periopaper strip was inserted immediately in between the two jaws periotron 8000 (Figure 1) then the periopaper strips were placed in a sterile test tube (5 ml) containing 500 microliter Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) with a PH=7.4 and centrifuged at 400 rpm for 10 minutes by centrifuge, after that the supernatant was taken from the test tube and placed in a separated eppendroff tubes (1.5 ml), these eppendroff tubes were stored at -20oC until further analysis [11].

Figure 1: Periotron 8000.

The pooled Interleukine-1β (IL-1β) concentration (before and after intervention) was obtained by using the dilution equation (C1V1=C2V2), after obtaining the diluted Interleukine-1β (IL-1β) concentration from a standard curve of ELIZA test, thus the pooled concentration (C1)=diluted concentration (C2) multiplied by dilution factor, where the dilution factor=final volume/initial volume of gingival crevicular fluid.

Results

Gingival crevicular fluid

The mean gingival crevicular fluid volume before intervention is not significant between groups, while it is lower in study group than in control one after using RP mouthwash and placebo for study and control group respectively with significant difference (Table 1).

| Phases | Groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Control | T | df | P value | |||

| Mean (μL) | ± SD | Mean (μL) | ± SD | ||||

| Before | 0.645 | 0.378 | 0.457 | 0.329 | 1.677 | 38 | 0.102^ |

| After | 0.349 | 0.173 | 0.771 | 0.45 | 3.915 | 38 | 0.000* |

| Mean ± SD | 0.296 ± 0.262 | -0.314 ± 0.306 | |||||

| Paired T test | 5.051 | 4.583 | |||||

| df | 19 | 19 | |||||

| P value | 0.000* | 0.000* | |||||

| Effect size | 1.129 | 1.026 | |||||

| ^=not significant at p>0.05, *=significant at p<0.05 | |||||||

Table 1: Descriptive and statistical test of gingival crevicular fluid volume (μL) among groups and different time intervals.

Regarding the change in the mean gingival crevicular fluid volume, it significantly decreased from 0.645 ± 0.378 μL to 0.349 ± 0.173 μL after using RP mouthwash in study group, while in control one it significantly increased from 0.457 ± 0.329 μL 0.771 ± 0.450 μL after using placebo as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Distribution of mean gingival crevicular fluid volume (μL) before and after using mouthwash by groups.

Human Interleukine-1 β (IL-1β)

The mean human Interleukine-1β (IL-1β) concentration before using the mouthwash in study and control groups is not significant between them, while it is lower in study group than that in control one with significant difference after using RP mouthwash and placebo in study and control group respectively (Table 2).

| Phases | Groups | T | df | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Control | ||||||

| Mean (pg/L) | ± SD | Mean (pg/L) | ± SD | ||||

| Before | 504.127 | 353.105 | 690.656 | 450.494 | 1.457 | 38 | 0.153^ |

| After | 159.288 | 150.726 | 1550.264 | 693.167 | 8.769 | 38 | 0.000* |

| Mean ± SD | 344.839 ± 329.322 | -859.609 ± 606.306 | |||||

| Paired T test | 4.683 | -6.341 | |||||

| Df | 19 | 19 | |||||

| P value | 0.000* | 0.000* | |||||

| Effect size | 1.047 | -1.418 | |||||

| ^=not significant at p>0.05, *=significant at p<0.05. | |||||||

Table 2: Descriptive and statistical test of human interleukine-1β (pg/L) among groups and phases.

Regarding the change in the mean human interleukine-1 β concentration (IL-1β), it significantly decreased in study group from 504.127 ± 353.105 to 159.288± 150.726 after using RP mouthwash while in control group it significantly increased from 690.656 ± 450.494 to 1550.264 ± 693.167 after using placebo as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Mean human Interleukine-1β (IL-1β) concentration before and after mouthwash between groups.

Concerning the correlation between the mean gingival crevicular fluid volume and mean interleukine-1β concentration this study demonstrated that there is a positive significant correlation between them in both study and control group as shown in Table 3.

| Groups | IL-1β | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF) | r | 0.512 |

| p value | 0.021* | ||

| Control | Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF) | r | 0.506 |

| p value | 0.023* | ||

| *=significant at p<0.05, ^=not significant p>0.05 | |||

Table 3: Correlation of gingival crevicular fluid with interleukine-1β.

Discussion

An attempt of initial gingival crevicular fluid investigation was done to relate its formation in relation to inflammatory changes in the connective tissues that underline the sulcular as well as junctional epitheliam [12]. The most common inflammatory changes include increase in vascular permeability that may be induced by mechanical and/or chemical means. Early studies reported that in the gingival crevicular fluid various substances were appeared that introduced into the parenteral circulation [13,14].

Regarding the change in gingival crevicular fluid volume, the present study reveals that the mean gingival crevicular fluid volume find to significantly decreases from 0.645 μL to 0.349 μL (after using RP mouthwash) in study group, while in control group the mean GCF volume significantly increases from 0.457 μL to 0.771 μL (after using placebo) and this finding may be attributed to anti-inflammatory effect of RP mouthwash (resolution of inflammation) as the association between the increased gingival crevicular fluid volume and increased severity of inflammation was supported by many previous literatures [15-18]. Additionally the RP mouthwash has the ability to disrupt biofilm formation as the presence of dental biofilm may cause an increase in the osmotic gradient, which is followed by an increase in a proteins leakage, this may cause an increase in hydrostatic pressure as well as vascular permeability thereby exceeding the lymphatics capacity to drain the fluids thus leading to up regulation of gingival crevicular fluid flow [19].

Concerning the interleukine-1β, many studies revealed that it is released by immune and non-immune cells in response to an infection, injury, invasion, as well as inflammation [20,21]. The present study reveals the mean IL-1β concentration in GCF significantly decreased in study group from 504.127 pg/L to 159.288 pg/L (after using RP mouthwash) while in control group it significantly increases from 690.656 pg/L to 1550.264 pg/L (after using placebo), these findings may be attributed to the ability of RP mouthwash to suppress the inflammatory response by reducing the level of this proinflammatory cytokine, this finding in in agreement with other studies which revealed that the RP reduces COX-2 activity and no production and this is the cause for its potential anti-inflammatory activity [22,23]. On the basis of our knowledge, as there is no previous in vivo study regarding the impact of RP mouthwash on gingival crevicular fluid IL-1β level, so more studies needed to be conducted to confirm these findings?

Conclusion

From the findings of this study it was concluded that the RP leaf extract might reduce the mean gingival crevicular fluid volume and mean interleukine-1β concentration after being used as a mouthwash by patients with a moderate gingivitis and improving the gingival conditions to a mild type for those patients, so it possess an anti-inflammatory effect, and thus it may be considered as a promising oral health care plant product.

Ethical Approval

This research was approved from a research ethics committee/university of baghdad/college of dentistry according to a decision report (Ref. number: 373/date 30-9-2021).

References

- Bussmann RW, Swartzinsky P, Worede A, et al. Plant use in odo-bulu and demaro, bale region, Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 2011; 7:1-21.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Souza SL, Taba Jr M. Cross-sectional evaluation of clinical parameters to select high prevalence populations for periodontal disease: The site comparative severity methodology. Braz Dent J 2004; 15:46-53.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uitto VJ. Gingival crevice fluid: An introduction. Periodontol 2000 2003; 31:9-11.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muthee JK, Gakuya DW, Mbaria JM, et al. Ethnobotanical study of anti-helmintic and other medicinal plants traditionally used in Loitoktok district of Kenya. J Ethnopharmacol 2011; 135:15-21.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berhanu A. Microbial profile of Tella and the role of gesho (Rhamnus prinoides) as bittering and antimicrobial agent in traditional Tella (beer) production. Int Food Res J 2014; 21.

- Chen G, Mutie F, Xu YB, et al. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory activities and polyphenol profile of Rhamnus prinoides. Pharmaceuticals 2020; 13:55.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Mujamaii K, Al Waheb A. Evaluation of anti-bacterial effect of Rhamnus Prinoides mouthwash on Streptococcus mutans count in a group of orthodontic patients with gingivitis. Mustansiria Dent J 2022; 18:12-16.

- Saloom HF, Papageorgiou SN, Carpenter GH, et al. Impact of obesity on orthodontic tooth movement in adolescents: A prospective clinical cohort study. J Dent Res 2017; 96:547-554.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gul SS, Griffiths GS, Stafford GP, et al. Investigation of a novel predictive biomarker profile for the outcome of periodontal treatment. J Periodontol 2017; 88:1135-1144.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Attar N, Banodkar A, Gaikwad R, et al. Evaluation of gingival crevicular fluid volume in relation to clinical periodontal status with periotron 8000. Int J Applied Dent Sci 2018; 4:68-71.

- Gabr AM, El-Guindy HM, Saudi HI, et al. Evaluation of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand and osteoprotegerin levels in saliva and gingival crevicular fluid in patients with chronic periodontitis. Tanta Dent J 2017; 14:83.

- Fatima T, Khurshid Z, Rehman A, et al. Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF): A diagnostic tool for the detection of periodontal health and diseases. Molecules 2021; 26:1208.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Griffiths GS. Formation, collection and significance of gingival crevice fluid. Periodontol 2000 2003; 31:32-42.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barros SP, Williams R, Offenbacher S, et al. Gingival crevicular fluid as a source of biomarkers for periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2016; 70:53-64.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brill N. The gingival pocket fluid. Studies of its occurrence, composition and effect. Thesis 1962.

- Loe H, Holm Pederson P. Absence and presence of fluid from normal and inflamed gingivae. Periodontics 1965; 3:171-177.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tollefsen T, Saltvedt E. Comparative analysis of gingival fluid and plasma by crossed immuno electrophoresis. J Periodontal Res 1980; 15:96-106.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alwan A. Determination of Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and Interleukin-6 (IL6) in gingival crevicular fluid in patients with chronic periodontitis. J Dent Med Sci 2015; 14:81-90.

- Newman MG, Takei H, Klokkevold PR. Newman and Carranza's clinical periodontology E-Book: Newman and Carranza's clinical periodontology E-Book. Elsevier health sciences. 2018.

- Giannopoulou C, Cappuyns I, Mombelli A. Effect of smoking on gingival crevicular fluid cytokine profile during experimental gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol 2003; 30:996-1002.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaddox LM, Goncalves PF, Vovk A, et al. LPS induced inflammatory response after therapy of aggressive periodontitis. J Dent Res 2013; 92:702-708.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cho H, Yun CW, Park WK, et al. Modulation of the activity of pro-inflammatory enzymes, COX-2 and INOS, by chrysin derivatives. Pharmacol Res 2004; 49:37-43.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cao H, Yu R, Tao Y, et al. Measurement of cyclooxygenase inhibition using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2011; 54:230-235.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Author Info

Karrar N Al-Mujamaii* and Athraa M Al Waheb

Department of Pedodontic and Preventive Dentistry, College of Dentistry, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, IraqCitation: Karrar N Al-Mujamaii, Athraa M Al Waheb, Anti-inflammatory effect of Rhamnus prinoides Mouthwash in Relation to Gingival Crevicular Fluid Volume and IL-1? in a Group of Orthodontic Patients (In Vivo Study), J Res Med Dent Sci, 2023, 11 (06): 006-010.

Received: 04-May-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-62809; , Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-62809 (PQ); Editor assigned: 06-May-2022, Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-62809 (PQ); Reviewed: 20-May-2022, QC No. JRMDS-22-62809; Revised: 26-May-2023, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-62809 (R); Published: 06-Jun-2023