Research - (2021) Volume 9, Issue 6

A Study of Quality of Life and Co-Morbid Depression in Persons Suffering from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Ajay Kumar and S Nambi*

*Correspondence: S Nambi, Department of Psychiatry, Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital, India, Email:

Abstract

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is the fourth commonest mental disorder with disability in severe cases often comparable to the disability associated with mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. OCD is one of the top IO disabling disorders as reported by WHO. To assess relationship of depression on quality-of-life m persons suffering from obsessive compulsive disorder. It is a comparative study; total sample size is 32 who satisfied the inclusion criteria and gave informed consent to be included in the study. The mean QOL scores in all domains were lower in the OCD than the control group. (Physical QOL, p=<0.001, Psychological QOL, p=<0.001, social QOL, p=0.001, environmental QOL, p=<0.001). this shows that quality of life is poorer in the OCD group in comparison to the control group. This current study indicates that the quality of life in persons suffering from OCD can be effectively improved by simultaneous treatment of OCD and co morbid depression.

Keywords

Obsessive-compulsive disorder OCD, Depression, Schizophrenia, Bipolar disorder

Introduction

Excessive thoughts (obsessions) that lead to repetitive behaviours (compulsions). Obsessive-compulsive disorder is characterised by unreasonable thoughts and fears (obsessions) that lead to compulsive behaviours. OCD often centres on themes such as a fear of germs or the need to arrange objects in a specific manner. Symptoms usually begin gradually and vary throughout life. Treatment includes talk therapy, medication, or both. OCD is one of the top IO disabling disorders as reported by WHO. However, till recently it was a rare disorder with a prevalence rate of less than 5 per 1000 adults. Epidemiological studies have shown that roughly about 2% of adults suffer from this intriguing disorder. It is now evident that the prevalence of OCD in adolescents is comparable to that in adults although the exact prevalence of OCD in children is not known. Despite such a high prevalence only a minority of sufferers seek treatment and that too after several years of silent suffering. This is because of the secretive nature of the condition.

The OCD usually begins in adolescence or early adulthood although it can begin in childhood. Nearly 65% of the persons have their onset before age 25 whereas fewer than 15% have onset after age 35 [1-4]. In our clinic samples most, persons had onset before 18 years [3]. The following are the common obsessive-compulsive symptoms (Table 1). Thus, the study aimed to assess the quality of life and prevalence of depression in persons suffering from obsessive compulsive disorder in a general hospital outpatient set up.

| Obsessions | % | Compulsions | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fear of contamination | 61 | Cleaning and washing | 50 |

| Aggressive th oughts , images & impulses | 43 | Ordering | 41 |

| Need for symmetry | 35 | Repeating | 38 |

| Sexual | 31 | Checking | 18 |

| Religion | 30 | Hoarding | 7 |

| Pathological doubt | 21 | Miscellaneous | 41 |

| Miscellaneous | 40 |

Table 1: Common obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted after getting ethical clearance from the University ethical committee. It is a comparative study; total sample size is 32 who satisfied the inclusion criteria and gave informed consent to be included in the study. The study group consisted of persons of both sexes, 18 years and above with obsessive compulsive disorder attending the psychiatry outpatient of SBMCH, who satisfied the inclusion criteria and gave informed consent to be included in the study.

Inclusion criteria

• Age group 18 to 50 years with age, sex and socio demographic matched general population.

• No current or history of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Exclusion criteria

• Present and history of schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, psychosis, recurrent.

• Substance abuse other than nicotine.

• Depressive disorder.

Results

Comparison socio-demographic variables between OCD and control groups

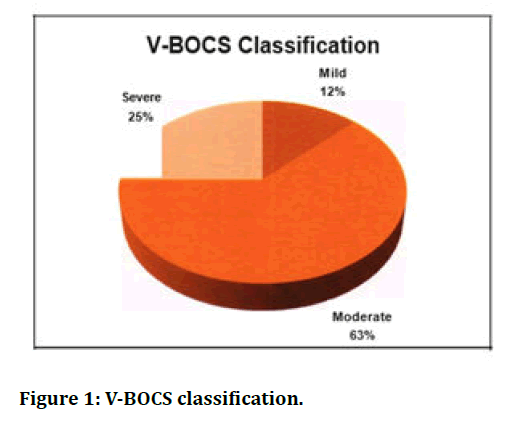

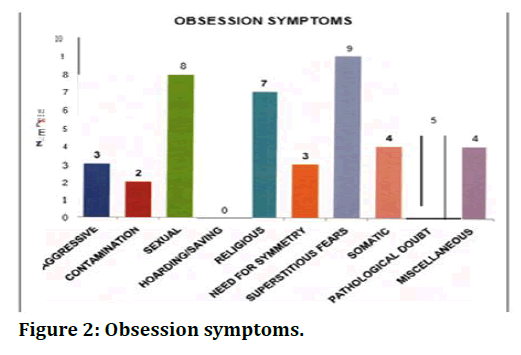

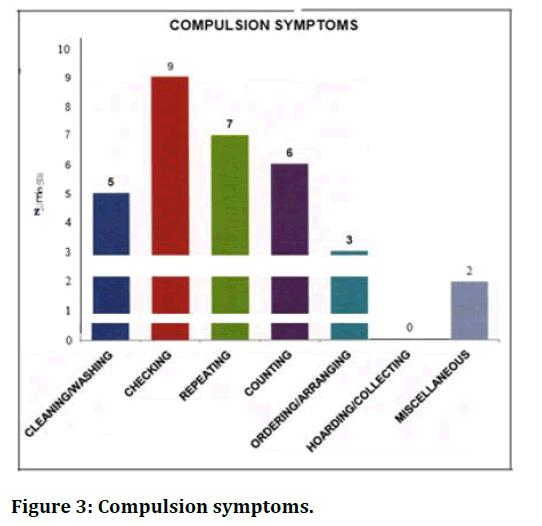

Results are detailed in Table 2 to Table 5 and Figure 1 to Figure 3.

| Group | N | Mean | Std. Dev | t-value | P - Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE | OCD | 32 | 31.47 | 8.602 | 0.029 | 0.977 |

| Control | 32 | 31.53 | 8.504 |

Table 2: T-Test to compare mean age.

| Group | Total | x2 value | P-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCD | Control | N | % | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | ||||||

| Sex | Male | 20 | 62.5 | 20 | 62.5 | 40 | 62.5 | 0 | 1 |

| Female | 12 | 37.5 | 12 | 37.5 | 24 | 37.5 | |||

| Total | 32 | 100 | 32 | 100 | 64 | 100 | |||

| Ses | Lower SES | 4 | 12.5 | 4 | 12.5 | 8 | 12.5 | 0 | 1 |

| Middle SES | 3 | 9.4 | 3 | 9.4 | 6 | 9.4 | |||

| High SES | 25 | 78.1 | 25 | 78.1 | 50 | 78.1 | |||

| Total | 32 | 100 | 32 | 100 | 64 | 100 | |||

| Education | Primary | 1 | 3.1 | 1 | 3.1 | 2 | 3.1 | 0 | 1 |

| Secondary | 12 | 37.5 | 12 | 37.5 | 24 | 37.5 | |||

| Graduate | 18 | 56.2 | 18 | 56.2 | 36 | 56.2 | |||

| Post Grad. | 1 | 3.1 | 1 | 3.1 | 2 | 3.1 | |||

| Total | 32 | 100 | 32 | 100 | 64 | 100 | |||

Table 3: Chi-square test to compare the proportions.

| Y-BOCS | Frequency | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | 4 | 12.5 |

| Moderate | 20 | 62.5 |

| Severe | 8 | 25 |

| Total | 32 | 100 |

Table 4: Prevalence of-BOCS severity in subject group.

| GROUP | N | Mean | Std. Dev | t - Value | P - Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical QOL on 0-100 scale | OCD | 32 | 42.62 | 13.437 | 8.954 | <0.001* |

| Control | 32 | 67.06 | 7.603 | |||

| Psychological QOL on 0-100 scale | OCD | 32 | 35.44 | 12.176 | 10.867 | <0.001 * |

| Control | 32 | 64.81 | 9.251 | |||

| Social QOL on 0-100 scale | OCD | 32 | 45.97 | 20.857 | 5.093 | <0.001 * |

| Control | 32 | 66.38 | 8.871 | |||

| Environmental QOL on 0-100 scale | OCD | 32 | 51.84 | 14.503 | 4.514 | <0.001 * |

| Control | 32 | 65.38 | 8.791 | |||

| *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level. | ||||||

Table 5: Student't'-Test to compare the mean QOL between OCD and Control groups in each domain.

Figure 1. V-BOCS classification.

Figure 2. Obsession symptoms.

Figure 3. Compulsion symptoms.

Discussion

This study was hospital based and cross sectional like most of the studies done in this field. In this, OCD group contained persons who were diagnosed to have obsessive compulsive disorder according to standard criteria (ICD-10 diagnostic guidelines) and by a Professor in Psychiatry. The control groups were age, sex and socio demographic matched general population.

The OCD group contained 32 subjects with diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder and the control group 32 subjects with age, sex and socio demographic matched general population. The mean age of the OCD group is 31.47 ± 8.6 years and that of control group as 31.53 ± 8.5 years with a p value of 0.977. There were 20 males and 12 females in the OCD as well as control group with a p value of 1.000. There was no significant difference between the educational and socio-economic status of the two groups.

Illness characteristics

This study examined the quality of life in persons with OCD in comparison to the control population. This was studied using World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale, brief version (WHOQOL-BREF) which contained 26 questions. This scale examined quality of life in 4 different domains (Physical, psychological, social, and environmental). Earlier studies had used different scales for assessing quality of life. In a previous study researchers used the 36-Item Short Form (SF-36) to assess the quality of life in OCD subjects [5-24].

Conclusion

The quality of life of OCD persons was poor when compared to control population in all domains. OCD persons had poorer score in physical, psychological, social, and environmental domains. The severity of disease had a significant influence on quality of life in OCD persons. As the severity increases quality of life decreases and the more impact was on physical and psychological domains and impact on social and environmental domains were statistically not significant. 50% of persons suffering from OCD in the study group were having co morbid depression; this clearly demonstrates the importance of assessing co morbid depression for the effective management of OCD. The depression in OCD persons had a significant influence on quality of life and it was poor when compared to nondepressed OCD persons. This current study indicates that the quality of life in persons suffering from OCD can be effectively improved by simultaneous treatment of OCD and co morbid depression.

Funding

No funding sources.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The encouragement and support from Bharath University, Chennai is gratefully acknowledged. For provided the laboratory facilities to carry out the research work.

References

- Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ et al. The cross-national epidemiology of obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:5-10.

- Jenkins R, Bebbington PE, Brugha T, et al. The national psychiatric morbidity surveys of great britain: I. Strategy and methods. Psychological Med 1997; 27:765-774.

- Jaisoorya TS, Janardhan Reddy YC, Srinath S. The relationship of obsessive-compulsivedisorder to putative spectrum disorders: Results from an Indian study. Comprehensive Psychiatr 2003; 44:317-323.

- Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL. Phenomenology and clinical features of obsessive-compulsive disorder. In: Obsessive compulsive disorders: Practical Mangement, 3rd Edn. Edited by Jenike MA, Baer L, Minichiello WE. St.Louis, MO, CV Mosby, 1998; 12-43.

- Eisen JL, Goodman WK, Keller MB, et al. Patterns of remission and relapse in obsessive compulsive disorder: a 2-year prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:346-351.

- Skoog G, Skoog I. A 40-year follow-up of patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:121-132.

- Ravissa L, Maina G, Bogetta F. Episodic and chronic obsessive compulsive disorder. Depress Anxiety 1997; 6:154-158.

- Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB et al. The epidemiology of obsessive compulsive disorder in five US communities. Archives Gen Psychiatr 1988; 45:1094-1099.

- Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. The cross-national epidemiology of obsessivecompulsive disorder. The Cross National ColJaborative Group. J Clin Psychiatr 1994; 55:5.

- Jaisoorya TS, Janardhan Reddy YC, Srinath S. The relationship of obsessive-compulsive disorder to putative spectrum disorders: Results from an Indian study. Comprehensive Psychiatr 2003; 44:317-323.

- Chen YW, Disalver SC. Comorbidity for obsessive-compulsive disorder in bipolar and unipolar disorders. Psychiatry Res l995; 59:57-64.

- Stavraki C, Vargo B. The relationships of anxiety and depression: a review of the literature. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 149:7-16.

- Abramowitz JS, Foa EB. Does comorbid major depressive disorder influence outcome of exposure and response prevention for OCD? Behav Ther 2000 ;3 l :795-800.

- Angst J, Gamma A, Endrass J, et al. Obsessive-compulsive severity spectrum in the community: Prevalence, comorbidity, and course. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2004; 254:156-164.

- Demal U, Lenz G, Mayrhofer A, et al. Obsessive compulsive disorder and depression. A retrospective study on course and interaction. Psychopathol 1993; 26:145-150.

- Sasson Y, Zohar J, Chopra M, et al. Epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder: A world view. J Clin Psychiatr 1997; 58:7-10.

- Apter A, Horesh N, Gothelf D, et al. Depression and suicidal behavior in adolescent inpersons with obsessive compulsive disorder. J Affect Disord 2003; 75:181-189.

- Moritz S, Meier B, Kloss M, et al. Dimensional structure of the Yale Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS). Psychiatry Res 2002; 109:193-199.

- Moritz S, Meier B, Hand I, et al. Dimensional structure of the hamilton depression rating scale in persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res 2004; 125:171-180.

- Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Pfanner C, et al. The clinical impact of bipolar and unipolar affective comorbidity on obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Affect Disord 1997; 46:15-23.

- Koran LM, Thienemann ML, Davenport R. Quality of life for patientswith obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:783-788.

- Sorensen CB, Kirkeby L, Thomsen PH. Quality of life with OCD. A self-reported survey among members of the Danish OCD Association. Nord J Psychiatry 2004; 58:231-236.

- Hollander E, Kwon JH, Stein DJ, et al. Obsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders: Overview and quality of life issues. J Clin Psychiatr 1996; 57:3-6.

- Lochner C, Mogotsi M, du Toit PL, et al. Quality of life in anxiety disorders: a comparison of obsessive-compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder. Psychopathol 2003; 36:255-262.

Author Info

Ajay Kumar and S Nambi*

Department of Psychiatry, Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, IndiaCitation: Ajay Kumar, S Nambi, A Study of Quality of Life and Co-Morbid Depression in Persons Suffering from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, J Res Med Dent Sci, 2021, 9(6): 192-197

Received: 08-May-2021 Accepted: 18-Jun-2021